Tapestry Opera’s Tap:Ex series will take the stage with their latest piece, Forbidden, from Feb. 8th until Feb. 11th at the Ernest Balmer Studio in Toronto’s Distillery District.

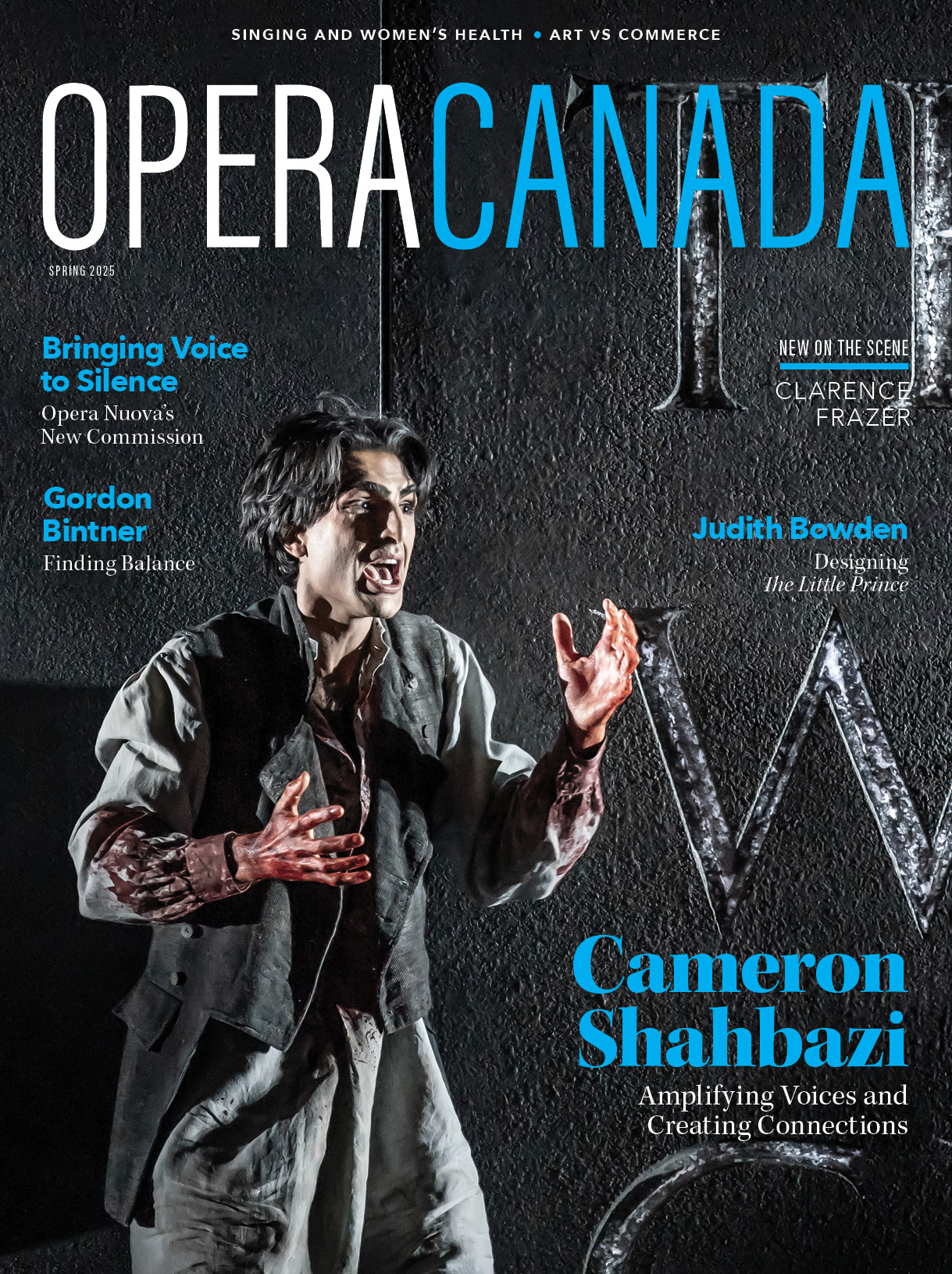

Iranian-born composer, Afarin Mansouri has created a blend of Persian, opera, rap, and hip-hop music with libretto by Afro-Caribbean hip hop artist, Donna-Michelle St. Bernard. Stage Direction will be by Michael Hidetoshi Mori and Music Direction by Michael Shannon. The opera features soprano, Neema Bickersteth, mezzo-soprano Shirin Eskandani, baritone Alexander Hajek, Farsi rapper/spoken-word artist, Saye Sky and Persian musicians, Padideh Ahrarnejad, Ali Massoudi, and Kianoush Khalilian.

Tapestry’s Tap:Ex series is known for its innovative and revolutionary take on stories, and in this iteration Forbidden will explore the story of a child (a representation of consciousness) being punished for a transgression that she does not understand. During the punishment she encounters Lucifer, who shows the child abuses of authority by people in power, tempting her to go against the rules.

Forbidden explores cultural taboos

A series of vignettes will show universal, ‘forbidden’ taboos related to gender, sexuality, religion, and culture. The child will encounter different scenarios, such as Tai Chi practitioners who invite positive energy and peace as an opposition to dictatorship. In another scene, two souls form a bond, but because of religious beliefs about homosexuality, they cannot be together.

“The point of the story,” says Mansouri, “is for this child or consciousness to [become] fully aware or enlightened by witnessing all of these things. She will get to the point where she believes she can make a change.”

The blend of Persian instrumentals, hip hop, rap and opera creates a new fusion of music, representing the many different emotions and difficulties portrayed in the show. Mansouri uses her Iranian background to showcase a different style of music for not only Western listeners but also, people from Iran, as “opera was forbidden in Iran after the revolution.”

Mansouri explains how her Iranian heritage has also influenced her music, and that each instrument is suited to a particular singer and the roles they play.

“The rapper in Forbidden is being modeled after something in Iran that we call ‘Pardekhan’ which is somebody who is basically a storyteller who becomes different characters. He helps us to see what’s in the mind of each character that you see on the stage.”

Mansouri goes on to explain how the Persian instrument Ney, which is associated with a feeling of nostalgia and longing, is used to compliment the rhythm of the rapper as well as representing a spiritual motif throughout the opera.

Traditional Persian instruments

Many other instruments used in the opera such as Tonbak, Daf, Udu and Tar also have historical significance and are symbolic in Persian culture across various regions.

The Tonbak is a Persian goblet-shaped drum used to prepare souls to become stronger. The Udu originated in Nigeria and is used in ceremonies in the southern part of Iran where folk music is enjoyed. In Forbidden, the Udu produces a seductive melody which suits Lucifer’s influence over the child. The Daf is connected to spiritual music used in Sufism, a sect of Islamic mysticism. The Tar is used in the journey of the child as well as other characters.

Saye Sky, Shirin Eskandani, Neema Bickersteth and Alexander Hajek rehearsing for Tapestry Opera’s Tap:Ex Forbidden. Photo: Sahar Khan

Librettist Donna-Michelle St. Bernard explains how Forbidden’s blend of music genres pushes the boundaries of not only opera itself, but each person’s practice of their discipline. There were many instances during the rehearsal period when clapping, stomping and shouting were spontaneously added, lending new dynamics and impact to the opera.

Fusion of styles

“[Persian and hip hop] both share an aspect of spontaneity within an apparent structure. They are forms that prioritize individuality, and have elements of a resistance tradition inside of them, and that very much speaks to the themes of Forbidden,” she says. “The forms of music that we’re using speak to me of the pursuit of individualism within a rigid structure and sometimes against that rigid structure.”

St. Bernard would also like the audience to question their comfort with existing social structures that oppress some but privilege others.

“When you are the person who is being served by those structures you can choose to be blind to the way other people are oppressed by them,” she says. “So I hope [through this opera] that you gain an understanding of how you might be served at the expense of others.”