Keith Warner’s frenetic, conceptually driven production of Richard Strauss’s Elektra (1909) reinforced a musically brilliant performance of this brutal, uncompromising opera centered on a mythic daughter’s longing for revenge of the murder of her father, Agamemnon, by her mother Klytemnestra.

Staged here by Anna Kühnhold, this co-production with the Prague National Theatre and the Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe is set in a claustrophobic museum vault designed by Boris Kudlicka with Kaspar Glarner’s eclectic modern Mycenaean Greek costumes. Warner’s conceit was to lock a modern museum visitor obsessed with glass-cased relics of the House of Atreus into the vault, transmuting her into the archaic Greek princess Elektra.

Portraying the dysfunctional family

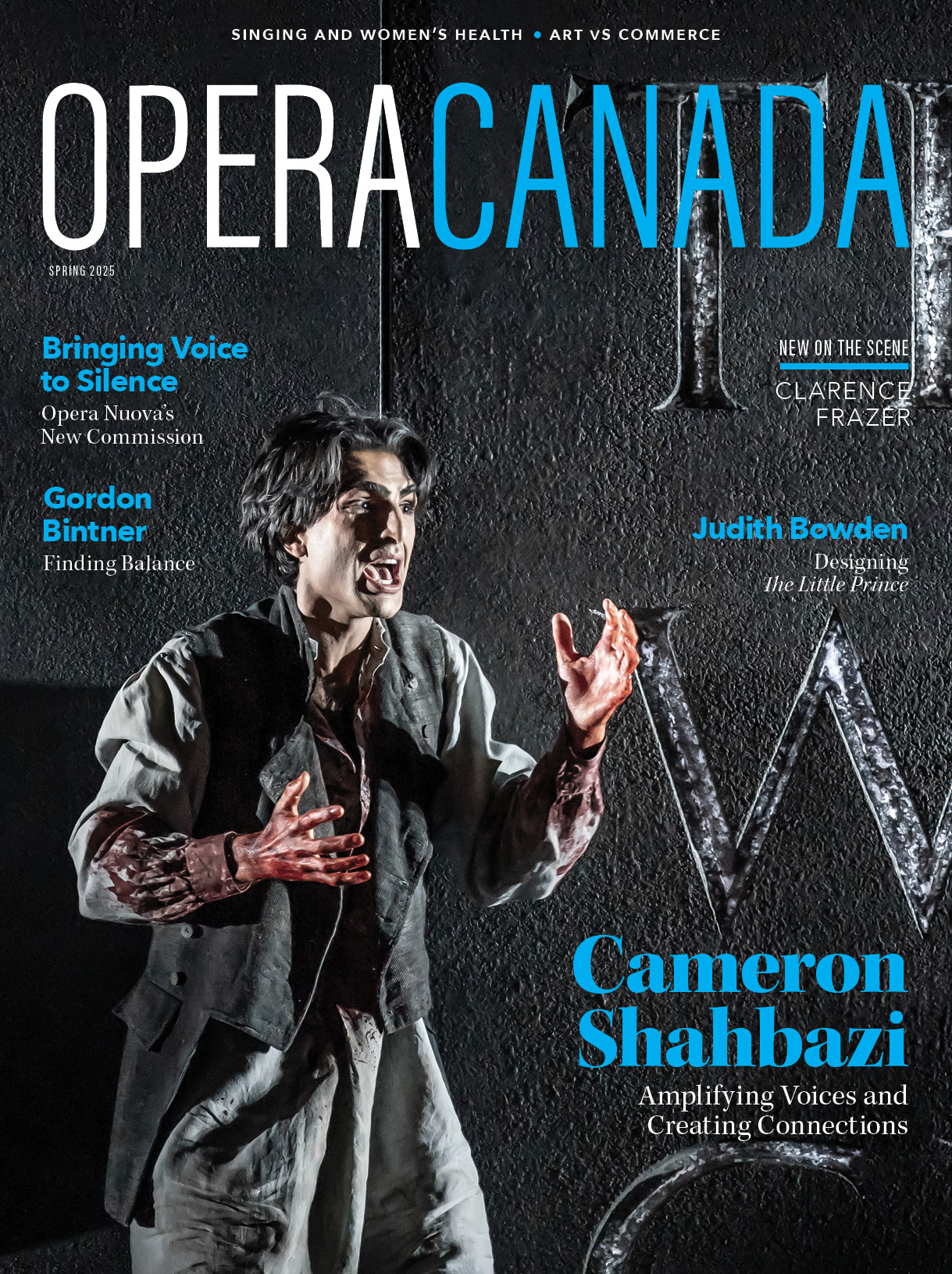

Christine Goerke dominated Elektra’s fearsome music, sporting the black draped poncho and basketball shoes of a graduate student—not the typical dirty rags of a princess who lives like an animal. She conveyed desperation succeeded by joy when her brother Oreste (an impressive Alfred Walker) appears to enact revenge—her impressive tone riding compellingly over the 95-piece Strauss orchestra. Goerke was vocally so superb that her largely semaphoric acting seemed irrelevant. Still, the director did prudently, and effectively, strand her on a bench for much of her triumphant dance frenzy at the end.

Adrianne Pieczonka as Chrysothemis in the SFO production of Elektra. Photo: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

The lucid, luscious soprano of Canadian superstar Adrianne Pieczonka fully embodied the beautiful sister Chrysothemis, desperate for all that Elektra’s revenge has shoved aside—love, children, peace of mind and, above all, a future. Pieczonka, clad in senior prom pink and sparkles, offered intense drama projected through elegant tone and phrasing with a voice evenly calibrated across every pitch and volume. Her refined, soft singing maintained a sense of urgency and was especially welcome in this noisy opera.

Instead of a wild, unhinged Klytemnestra, Michaela Martens portrayed an ample bourgeoise in sky blue satin, more in terror of dementia than an example of it. She sang her tortuous part with style and depth, hardly deserving decaptitation in the sink of a yellow 1950s suburban kitchen, which unaccountably intruded into the museum space from time to time.

Michaela Martens as Klytemnestra in SFO’s production of Elektra. Photo: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Strong Canadian presence in San Francisco

The five maidservants who open Elektra set the story’s frame, each get their chance to emerge as leading singers. Canadians Sarah Cambidge and Rhoslyn Jones made fine impressions in these parts. Cambidge is now a beginning Adler Fellow with the company, while Jones (in their program for young singers ten years ago), is advancing into an admirable career.

Conductor Henrik Nánási inspired taut, propulsive playing from the fine San Francisco Opera Orchestra. Though the sound was at times strident as the score demands, it more often emerged as lush, even Romantic, yielding a beautiful, touching, plangent Elektra to offset the more frenetic doings at its surface.