One of the great delights of today’s viewer technology is sitting in your living room, a cup of chocolate in your hand, and, before you, a vibrant, young orchestra, a brilliant and famous conductor, and a dozen notable first-class singers embarked…eroticism…genius – in other words, Salome. Thanks to Medici.tv’s ample coverage of significant classical music events across the globe, we can attend landmark performances, live and in replay. The live concert performance appears on screen straight from the world-famous Verbier Festival in the Swiss Alps thanks to Medici.tv, the premier music live-streaming instrument for viewers. All I had to do was press a button. Aladdin, indeed, had rubbed the lamp.

European Festivals

Verbier Festival, established in 1991, its first festival in 1994, was founded by Martin T:son Engstroem and is renowned for many things, among which are its over “100 free events that appeal to a wide audience with diverse musical tastes,” and an Academy for young musicians, which include Master Classes for a wide variety of instruments, including Opera and Art Song among other things. Notable performers too come to Verbier to perform and teach, from Yuja Wang, and Joshua Bell to Yefim Bronfman, Esa Pekka-Salonen, Thomas Hampson, and Andras Schiff, among others, to the young musicians who make up the orchestra itself. Verbier is a fine opportunity to explore the familiar and the new.

Concert versions of operas such as Salome, Elektra* (July 28th, streamed live by Medici.tv) make sense in more ways than one. Not only do they continue to present performers of opera throughout the summer, they further the chance for audiences to absorb the music itself without operatic panoply. In other words, more direct contact. In addition, through the medium of livestream, more of us can “attend” and be part of the world of music-making as it happens.

Salome

Richard Strauss’s one-act masterpiece stands up to time. First appearing in 1906, audiences saw the young Strauss as Wagner’s musical heir, with the story he chose, based on the renown and scandalous play by Oscar Wilde, itself derived from Gustave Flaubert’s story, Herodias. Further, Strauss worked with the renown Romain Rolland’s on a rendition of the French phrasing for his German text. Strauss seemed to carry Wagner’s original story choices for his music on as well. Prefacing the appearance of the extraordinary German dramatic soprano, Gun-Brit Barkmin playing Salome, were a flank of tenors and basses and contralto – soldiers, slaves, and page – who establish the beauty of the daughter of Herod in the no doubt sultry moonlight night. Barkmin’s entrance, even at a distance, sans costume, set and scenery was a sensation. Here was the teenage vamp whose voice is claret-rich, and which warms and chills simultaneously. Sleek and chic in her black sequined sheath with long, sheer sleeves, the cocky girl further charges the action with her probing, taunting, cajoling words: “Ich will nicht bleiben. Ich kann nicht bleiben.” (“I will not stay. I can not stay.”) Why? Because her step-father stares at her with his mole’s eyes, her mother’s husband. She is bored and confined, and as such, she looks for something else to release her. When she learns that Herod’s prisoner prophet Jochanaan is not old, her interest is piqued. Questioning Narraboth, and the soldiers in voice probing and sparkling, Salome brings us into her world, risky, sensual, dangerous. Although we do not yet know for sure, we more than wonder what this girl is capable of.

The opera plays only an hour insert…and throughout, Gun-Brit Barkmin holds the stage and all of us with her. Her vocal and dramatic range is extensive – probing, cajoling, taunting, by turns, she decides to go after the prisoner-prophet Jochanaan, first for challenge and then for desire. Played by Latvian bass-baritone, Egils Silins, in a black suit and tie, no torn prisoner-prophet cloak here, Silins’ Jochanaan matches the intensity of his new adversary, though righteousness is his calling card. “Wo ist er, dessen Sundenbecher jetzt voll ist?” (“Where is he whose cup of abomination is not full?”) He talks of Herod, condemning his depravity and then that of his wife, Herodias, Salome’s mother, and Salome begins to exult – “Er ist schrecklich. Er ist wirklich schrecklich” (“He is terrible, he is really terrible”), and “Ich muss ihn naher besehn” (“I must look at him closer”), “Ich bin verliebt in deinen leib.” (“I am in love with your body.”) “Lass mich ihn kussen, deinen mund…” (“I must kiss thy mouth…”)

Throughout, Silins’ Jochanaan defends himself with surly combat. To him, putting Salome down not only establishes his moral superiority, but through his Silins’s resonant voice deepening, darkening and expanding, he invests it with the conviction that this is the strongest weapon against her. As Salome rouses, however, she knows such a view falls before lust: He is a man, no? She dares him. Trumpets and horns, the full complement of winds, doubles and triples such love-combat. Weaving motifs into this plain of increasing hysteria, we hear touches of Strauss’s later Rosenkavalier. Saxophone and trumpet tease us into this young and giddy girl’s willful desire, but he builds the tension as she bends us to her will as well. Before long, we too are hooked, their voices ardent and baiting us as well; and all without a cistern to be seen.

Gerhard Siegel’s Herod, a tenor with a colorful and intricate range, conveys the complexity of the ruthless Tetrach, who also gets pushed to the wall. But, unlike Jochanaan, Salome keeps him well-posed in his evil domain. Murder? Mayhem? No problem. Thus, Siegel’s Herod has more vocal means to push back against Salome, both vocal and psychological. While he winces and whines to ply her with counter-offers to her demand for the man in his power, before long, her manipulating skills and her feminine charms overpower him. Until the two strike some sort of moderating bargain – her dance for Jochanaan’s head – his own senses rebel, and he is just about run over. His flexible tenor deftness keeps him from that crash and he rises from such a heat to commit the final crime this night brings to bear.

And what of the mother in the piece, Herodias? Played by American mezzo Jane Henschel, she provides both apt contrast to her fiery daughter, “Meine Tochter” and continuation of the on-going depravity. No slouch in the deceit and jealousy department, Herodias both rails against her flesh-and-blood rival prancing before her own husband, she begins to savor Salome as she gains control. Here we have a mother who sees the next generation, viz, her daughter, reach for and grab a new rung of the ladder against patriarchy. Her initial attempt to rein her in, – after all that’s what she was taught! – in voice soaring and underpinned by growls of relief and pleasure, Henschel’s Herodias savors it as things can only go forward from here. The brass – trombones and horns in particular – stir and express the dragon in both women as and the scene shimmers with its rising lust. Violins lift and cover the alternating play of passion, Herodias’ vocal variety a match for what else is on display. It is clear, neither mother nor daughter is foreign to exploitation.

Strauss draws us deeper and deeper into the primal world undergirding the whole opera as the contests between Herod and Herodias ensue, Salome and Jokannan, Salome and Narraboth, played by Andrew Staples. Through their contrast and counterpoint, a genie only strives to break out of the box. Until Silins’ blooming bass-baritone only seems to resist, despite its heroic words, and Salome’s rising excitement thrusts her desire further and further into the foreground, plus Herod’s agitation, succeeds in liberating it at last, the music goading them all to the inevitable conclusion.

Throughout the performance center stage always smolders. Soldiers and guards coming and going, transmitting valuable information to keep the action going, never disrupt it. Herod pulling at his collar and jacket as his step-daughter twirls through her Dance of the Seven Veils, as if actually twirling her clothes around his body itself doesn’t either. But, have we seen this dance, or not? We are not quite sure as Herod sings, “Ich kann nicht atmen,” (“I cannot breathe,”) and we are still without curtain, scrim, platform. All the time too, Salome will not be stopped. She has no qualms at doing what will shock the other. You don’t believe me? Hah. She will never change her mind, and that’s that. Not Faust’s bargain with the devil, but more than devilish nonetheless. It is the effect of one body on another as well as the mind.

The Dance of the Seven Veils offers an exquisite contrast to the harsh and vicious debate we have witnessed, and, despite it all, it is clear Salome has them in the palm of her hand. The more she is blocked, in fact, the more excited she becomes. Lust is her challenge, and she thrives on it. Shrillness and dissonance weave more force and project strength in Gun-Brit Barkmin’s voice, what will come next is anybody’s guess. And as she bends and twists, smiles, and teases, vocally, facially, with modest use of hands, we believe we have actually witnessed the dance that is not, in this concert performance, actually there.

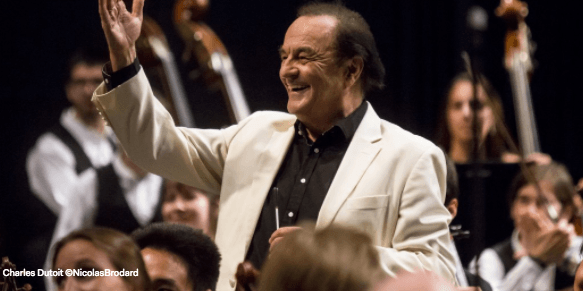

Charles Dutoit, legendary conductor Emeritus at Verbier, led the youthful orchestra – the Verbier talent ranges in age from 18–29 – which rose to the occasion. Not only did Dutoit lead with his hands, arms and facial intensity, but his whole being inspired and guided the orchestral talent, giving their all to the well-produced performance, so finely directed by Anais Spiro. At the end, they even unfurled a banner displaying “Merci, Charles,” as this was his final season.

Salome, no doubt Lolita’s original, as well as Wilde’s heroine and the ancient girl-woman archetype who sets her cap for a male prize, moves toward the brilliant final aria, with satisfaction as well as defiance. From pleading to prodding, from annoying to haranguing, she has sung herself both through and further into the very depravity of which she is bred. This is Salome at her most ardent and passionate. The prosecutor at her jury, persuading through vocal movement. Movement through orchestral and vocal sound, rich, various, touching on the shrill but without steel or tin, facial expression coupled with hand and arm – here is the acme of desire. Now a love-song to a dead man. From the belly of the orchestra the snarling, shameless lust, and through bursts of exceptional melody Strauss through Salome brings it together…flutes, oboe and piccolo, et al. Rapturous singing coupled with rich and various Straussian coloration – tambourine, clarinet and gorgeous oboe, string pizzicato, percussion including xylophone, harps, in ¾ time as well as castanets, create the musical tapestry and grant it lyricism as well as darkness. Barkmin’s Salome smiles with delight at her contribution: “Ich habe deinen lippen gekusst, Hat es nach Blut geschmeckt?” (“I have your lips kissed; have I your bloodsucked?”) Smiling and exultant, her hands folded under her neck, she asserts pleasure is where it should be, as the non-curtain comes down. An evening in Switzerland, a morning in America, moved and lifted out of its daily routine.

Medici.tv will continue to replay Salome until November 6th, with a subscription. On July 28th it livestreamed Strauss’s Elektra, from Verbier as well. Further livestreams of opera and various concerts and master classes continue to come to us in whatever country we live, so long as we have appetite to savor them.

Source: Opera stories from La Scena