In his 1888 polemic, The Case Against Wagner: A Musician’s Problem, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche cites Bizet’s Carmen as the perfect opera: “With it” he writes, “one bids farewell to the damp north and to all the fog of the Wagnerian ideal.”

J’Nai Bridges (on bench) as Carmen in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Carmen, 2022. Photo: Michael Cooper

Beyond its Mediterranean warmth and colour, however, Nietzsche valued Carmen for its vivid depiction of passionate carnal love. “Not the love of a “cultured girl!”—no Senta-sentimentality,” he continues, citing the heroine of Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer. “But love as fate, as a fatality, cynical, innocent, cruel,—and precisely in this way Nature! The love whose means is war, whose very essence is the mortal hatred between the sexes!—I know no case in which the tragic irony, which constitutes the kernel of love, is expressed with such severity, or in so terrible a formula as in the last cry of Don José with which the work ends: ‘Yes, it is I who have killed her, I—my adored Carmen.’”

OK, so the prose is a bit purple and the punctuation wayward, but Nietzsche has a point. As the Canadian Opera Company’s current production plays out, Carmen, for all its sunny music, dance-inflected rhythms and wry humour, is a very dark tale in which two lovers absolutely destroy each other. On opening night October 14, there was a palpable, disturbing, love-hate chemistry between American mezzo J’Nai Bridges’s Carmen and Argentine tenor Marcelo Puente’s Don José in Bizet’s extraordinary final scene. Carmen’s murder at the hand of a fatally emasculated José came across like the consummation, not the end, of a relationship doomed from the outset. When performed at that intensity, the scene is opera at its most visceral.

2022 Rubies Awards Gala

Monday, November 7, 2022 6PM

An Evening Celebrating Canadian Opera Artists

FOUR SEASONS CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS

TICKETS & INFORMATION

This is the COC’s fourth staging of a production first mounted in 2005 by American director Mark Lamos. Joel Ivany, now Artistic Director of both Edmonton Opera and Against the Grain Theatre, helms this 2022 revival of a work he also restaged for the company in 2016. Working with a fine ensemble cast, Ivany has ratcheted down the focus on the characters more effectively this time around, though some of the production’s built-in limitations remain hurdles.

Lighting designer Jason Hand did an effective job in bringing the various locales to warm life, while François St. Aubin’s original costumes are serviceably “Spanish” in look. One of the production’s idiosyncrasies is to ignore specific geographic references in the text to Navarre, Seville, Andalusia, Gibraltar and so on, and set the piece somewhere in 1930s Latin America (I thought it was Cuba, but nobody in this staging seems to smoke cigars). Nothing substantial was achieved by the relocation and update in 2005, and it still seems an empty, albeit harmless, idea today.

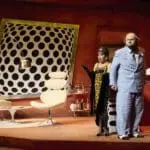

A scene from the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Carmen, 2022. Photo: Michael Cooper

Michael Yeargan’s original set designs, however, pose staging problems. Considering that crowds are essential to Carmen’s streetwise ambience, he made odd choices. Act 1 is dominated by a tall, gated fence running across the stage, with a large empty square and building behind, and a busy street running across the front. All the action is restricted to the narrow “street,” so, for example, the children cheering on the changing of the guard (sung by an energetic and ebullient Canadian Children’s Opera Company) are strung out side by side as if they’re in a number from A Chorus Line. For her entrance and “Habanera,” Carmen must navigate between the crowd and the fence, while Don José sits on a bench among the townsfolk in a straight line across the stage nonchalantly cleaning his sidearm. Act II fares better, though the design—a square filled with café tables and chairs, flanked by two tall buildings and leading to what looks no bigger than an alleyway—again restricts the larger-scale moments. While the stepped hillside and church ruin of Act III is more open, it also tends to push the action to a line across the front of the stage; only in the open space outside the bullring in Act IV do the singers have the space to create a physical drama to match the music (albeit, of course, only Carmen and Don José are on stage at this point). The scenic design often forces the action into two-dimensions or awkward corners; that the production works as well as it does is a triumph of music making in an inconvenient staging.

Almost 150 years after its premiere, one challenge of Carmen is that so many of the numbers in the score are so familiar and popular that the dramatic arc of a performance can devolve into a series of more-or-less well-connected musical highlights; the risk is even greater using, as this revival does, the original spoken dialogue to link the numbers. The COC largely avoids the trap, except perhaps for numbers that have by this time taken on an iconic life of their own. (Can Escamillo’s larger-than-life Act II entrance with the Toreador Song, for example, especially as exuberantly and resoundingly sung as it was here by American baritone Lucas Meachem, with paparazzi flash bulbs popping and admirers fawning, ever fit seamlessly into the dramatic flow?). Credit should start in the pit with conductor Jacques Lacombe, here making his company debut. From a well-judged reading of the contrasting moods of the overture to the highly charged tragic ending, Lacombe led a performance that was well paced, colorfully detailed and paid attention to the more intimate moments as well as the big scenes. The COC Orchestra responded with its customary musical aplomb, as did the men and women of the COC Chorus in their various guises as soldiers, smugglers, factory workers and sundry citizenry.

On stage, the ensemble of soloists was impressively in sync. Bridges, also making her company debut, is a seductively smoky—and sultry—voiced Carmen whose fluid movement and assertive attitude make Don José’s quick fall believable. Her reading of the cards in Act III, which Ivany put in pinpoint focus, added great depth to the character through its fatalistic self-reflection. The way Puente uses his head and chest voices gives his tenor a distinctive tonal palette, and he uses it as effectively to limn a love-struck character who progressively loses his agency as he does at the end to project a murderous jealousy. Don José’s hometown sweetheart, Micaëla, often comes across as a passively winsome counterpoint to Carmen. Soprano Joyce El-Khoury, quite apart from her compellingly sung solo numbers, neatly created a more spirited character, both in her Act I response to the soldiers’ advances and her encounter with the smugglers in Act III.

Joyce El-Khoury as Micaëla and Marcelo Puente as Don José Ⓒ Michael Cooper

The character roles were well handled by current and former members of the COC Ensemble Studio, with Ariane Cossette and Alex Hetherington as Frasquita and Mercédès, Carmen’s friends; Jonah Spungin and Jean-Philippe Lazure as Le Dancaïre and Le Remendado, the smugglers; and Alex Halliday and Alain Coulombe as the officer, Moralès, and the captain, Zuniga. Kudos to all for etching vivid fellow-travellers for the principals.

Carmen runs in repertory with Wagner’s Dutchman, which is an interesting pairing. Quite apart from the connection Nietzsche made between them, they fascinate as contrasting studies of two outsider female characters who are in full control of their own fates until the very end. In terms of history, the two pieces are also interesting as harbingers of operatic things to come—Dutchman of Wagner’s own later music dramas, and Carmen, especially that last scene, of verismo shockers on the late-century horizon.

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.

OCTOBER 14, 16, 20, 22, 26, 28, 30, AND NOVEMBER 4, 2022

CAST AND CREATIVE TEAMS

Conductor Jacques Lacombe

Director Joel Ivany

Lighting Designer Jason Hand

Original Set Designer Michael Yeargan

Original Costume Designer François St. Aubin

Fight Director and Intimacy Coordinator Siobhan Richardson

Price Family Chorus Master Sandra Horst

Carmen J’Nai Bridges, Rihab Chaieb (Oct 20 and 22)

Don José Marcelo Puente

Micaëla Joyce El-Khoury, Anna-Sophie Neher (Oct 28, 30, and Nov 4)

Escamillo Lucas Meachem, Gregory Dahl (Oct 30 and Nov 4)

Zuniga Alain Coulombe

Le Dancaïre Jonah Spungin

Le Remendado Jean-Philippe Lazure

Frasquita Ariane Cossette

Mercédès Alex Hetherington

Moralès Alex Halliday

With the COC Orchestra and Chorus

A Canadian Opera Company production

The COC Orchestra is generously sponsored, in part, by W. Bruce C. Bailey