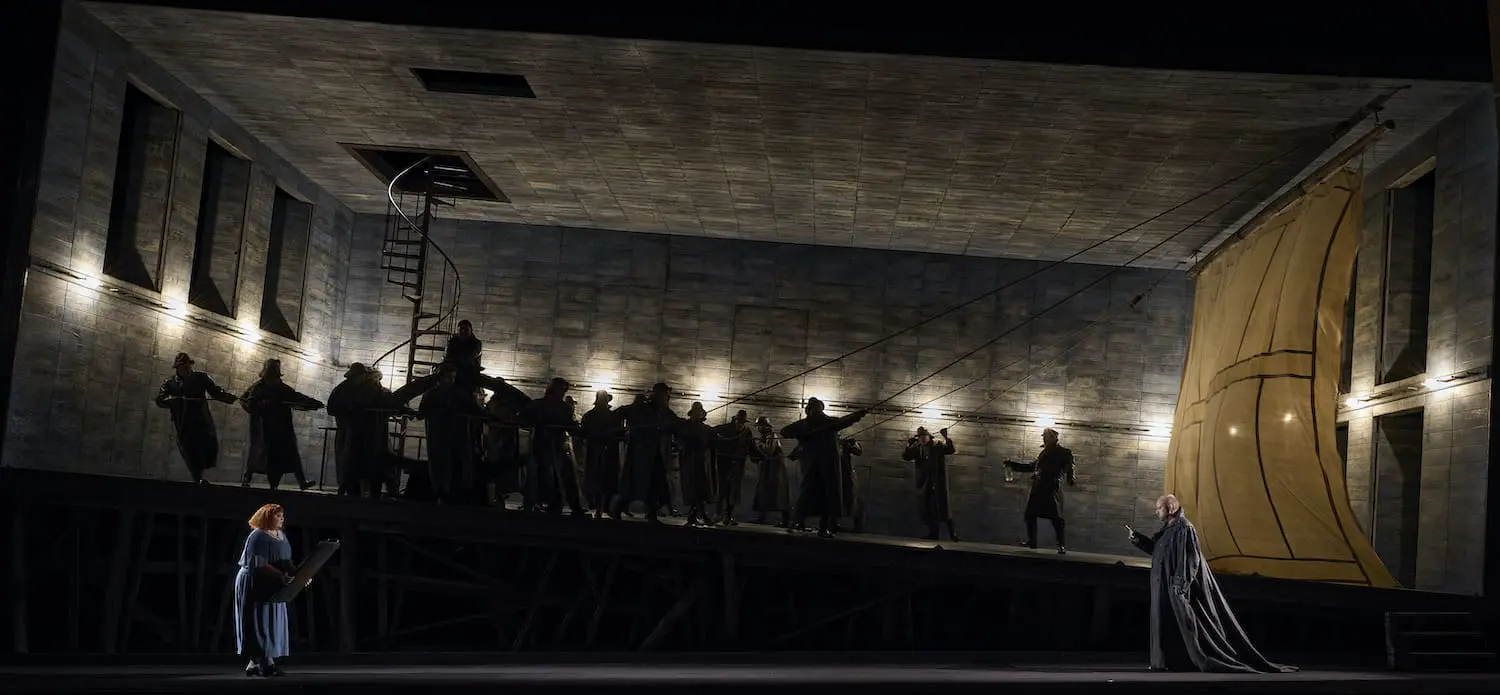

After almost three years in virtual drydock, the Canadian Opera Company launched its 2022/23 season October 7 with a gripping performance of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman. This is the company’s third revival of the production it commissioned in 1996 from American director Christopher Alden.

A quarter of a century on, and this time in the capable hands of revival director Marilyn Gronsdal, Alden’s dark take on Wagner’s ghostly tale of stormy seas, lost souls and dangerous obsessions is as compelling and provocative as ever—albeit with some of its original idiosyncrasies still intact. On the musical side, despite some minor glitches on stage and in the pit, opening night showed this revival is distinguished by the strongest ensemble the production has enjoyed in its hometown history.

This Dutchman was the first opera Johannes Debus conducted after his appointment as COC Music Director. Revisiting the show a dozen years later, he set it up dramatically with a vigorous account of the famous overture, and then led the orchestra through a richly detailed reading full of colour and dynamic contrasts. It’s been a while since the COC Orchestra has had an opportunity to tackle a Wagner score (without COVID shutdowns, it should have played both Dutchman and Parsifal by now), but there was nothing tentative about its performance. The chorus plays a major role in the earlier Wagner operas, and, despite some COVID-related setbacks that made for a difficult rehearsal period, Chorus Master Sandra Horst’s male and female voices made a strong impression throughout, their sailors and townsfolk becoming active protagonists. In this production, the chorus characterizes a closed society that neither welcomes outsiders nor readily tolerates difference or dissent.

2022 Rubies Awards Gala

Monday, November 7, 2022 6PM

An Evening Celebrating Canadian Opera Artists

FOUR SEASONS CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS

TICKETS & INFORMATION

In the title role, Danish baritone Johan Reuter is a looming presence both physically and vocally. Starting from the riveting opening monologue, in which the Dutchman bemoans his cursed fate, Reuter’s skill as both singer and actor builds an emotionally complex character, projecting the vulnerability and humanity that underlie his supernatural demonic possession. Soprano Marjorie Owens, though she spends much time in a static trance gazing either at a picture of the Dutchman or the character himself, is a sympathetic Senta, her instrument easily accommodating the full range of the role and notably deploying a fast vibrato that tends to sweeten and enrich her tonal colouring. The duet in which she pledges to save the Dutchman was movingly handled by both singers; it starts out coolly as a hesitant exchange between strangers but builds to a passionately intimate bonding.

Franz-Josef Selig as Daland, Miles Mykkanen (back, facing wall) as the Steersman, Christopher Ventris (front) as Erik, and Rosie Aldridge as Mary in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of The Flying Dutchman, 2022 Ⓒ Michael Cooper

As Senta’s father, Daland, the go-between who readily offers his daughter’s hand to the Dutchman in return for material riches, German bass Franz-Josef Selig is as self-satisfied and obsequious as he should be, his portrayal nicely avoiding the comic caricature of the grasping, money-hungry sea captain. Selig, however, did not benefit from the decision to split the performance into two acts separated by an intermission. The division, which Alden introduced when he staged the production for Dallas Opera in 2018, ends Act 1 with Senta’s startled “Ha!” when she first sees the Dutchman. Act II begins then—mid-scene in Wagner’s original—with a barely audible figure on the timpani, followed by Daland greeting his daughter and launching into his aria introducing the Dutchman. It sounds fine on paper, but in practice, the intermission has broken the dramatic flow and Daland’s aria has lost its context; the new Act II doesn’t pick up steam until the Senta/Dutchman duet.

In notes on the production of this opera, Wagner explicitly raised red flags about treating Senta and her would-be local lover, the huntsman Erik, in too sentimental a manner. Wagner saw both as strong characters in their own way. In the case of Erik, the danger is to portray him as a whining, lovelorn victim. Except perhaps for putting his own hunting rifle to his head and threatening to kill himself during the first encounter with Senta (a directorial intervention), English tenor Christopher Ventris avoids the pitfalls handily, his Erik impassioned, impetuous and clearly in a dark and dangerous frame of mind from the outset. His role in Senta’s death at the end (another directorial intervention) is at least believable.

The production makes more than usual of the two smaller roles of the Steersman and Mary, both well sung by American tenor Miles Mykkanen and, in her company debut, English mezzo Rosie Aldridge. There’s justification for enhancing the way Mary reacts to the Dutchman (or his picture, at least) since the libretto explicitly states that she first introduced Senta to his story, and there’s the implication that Mary understands Senta’s attraction to him even if she doesn’t approve. The reactions of the Steersman, which seem to oscillate from fear through incomprehension to compassion and back again, are more difficult to fathom. His actions through the feasting scene and the final tableau were prominent distractions, but to what end?

This is an impressionistic rather than realistic Dutchman—there are no ships, no spinning wheels, and, apart from projections of some storm clouds, the geography and stormy atmosphere are conjured mainly in the orchestra. Alan Moyer’s set is a box with a steep rake from left to right (and a gentler rake from back to front), with a menacingly fenced off space below that serves as a prison-like space for the Dutchman’s crew. The boxy space serves as Daland’s ship at the outset, the factory-like space for the spinning scene, Daland’s house for the meeting of Senta and the Dutchman, and finally the site of the party scene. The off kilter set works very well for a story in which all the characters are to some degree unhinged by their predicaments, and the voices project well from within it. It does, however, undermine the balance in one of the work’s highlights, the spooky double chorus that pits Daland’s on-stage crew against the Dutchman’s off-stage phantoms.

While location and time are ambiguous in the production, its visual aesthetic reflects the interwar period of German Expressionism. Moyer’s mauve and green costumes for the women in the celebration scene, for example, have the look and vivid colours of an Ernst Kirchner painting, while the picture of the Dutchman, which in this production is almost a character in itself, is a direct lift of Erich Heckel’s 1917 Man on the Plain-Self Portrait, a work in turn influenced by Edward Munch’s celebrated The Scream. Anne Militello’s atmospheric lighting is strikingly apt; the shadow play as Erik recounts his dream of Senta’s fate, for example, cleverly summons the look and feel of German 1920s-era horror films such as Dr. Mabuse and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

What to make, though, of the horizontally striped prison costumes of the Dutchman and his crew? It’s an open question as to what they are prisoners of—beyond, of course, the satanic curse embedded in Wagner’s original story line. That the townspeople wear arm bands and at one point appear to give a straight-arm Nazi salute has in the past raised discussion of the crew as concentration camp victims, though the production hardly advances this or any other specific historical agenda. Directors sometimes seem to view Wagner’s earlier operas through the lens of his later music dramas and make more of their import than the composer himself could, given his musical and philosophical development in the early 1840s. Dutchman was written at a time when operas featuring the supernatural and the fantastical were popular, and it’s probably best to take it mainly at its face value. For the most part, one of the COC’s oldest productions still in repertory lets the work unfold without too much conceptual overlay, and, as this opening night demonstrated, provides singers with a good framework for compelling performances.

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.

OCTOBER 7, 9, 13, 15, 19, 21, AND 23, 2022

CAST AND CREATIVE TEAMS

Conductor

Johannes Debus

Original Director

Christopher Alden

Revival Director

Marilyn Gronsdal

Set & Costume Designer

Allen Moyer

Lighting Designer

Anne Militello

Intimacy Coordinator

Lisa Stevens

Price Family Chorus Master

Sandra Horst

Dutchman Johan Reuter

Senta Marjorie Owens

Daland Franz-Josef Selig

Steersman Miles Mykkanen

Erik Christopher Ventris

Mary Rosie Aldridge

With the COC Orchestra and Chorus

A Canadian Opera Company production

Production underwritten in part by Lisa Balfour Bowen and Family in memory of Walter Bowen and in honour of Alexander Neef

The COC Orchestra is generously sponsored, in part, by W. Bruce C. Bailey