With Written on Skin, composer George Benjamin and librettist Martin Crimp have fashioned a svelte opera, as effective as a scalpel. With brisk 90-minute pacing, a small cast, and persuasive and accessible music, you could call it shrewd—political psychodrama for the Netflix generation. The Canadian staged premiere at Opéra de Montréal never got in its way (seen Jan. 25th).

Expectations were very high; Written on Skin has been roundly celebrated since its 2012 premiere at Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, but not everybody might thrill to the subject matter. Do we really need another romantic tragedy from the depths of history such as those used for other recent new operas Rufus Wainwright’s Hadrian (Canadian Opera Company, 2018), or Kaija Saariaho’s L’amour de loin (Salzburg Festival, 2000), when the world abounds in contemporary disasters? This trend seems like insecurity, conservative self-seclusion that risks opera’s cultural irrelevance, though Written is on the cleverest end of the spectrum since it’s basically a story about one woman’s self-liberation (written by two men). But in its attempt to create timeless types it gambles with characters who are not quite individuals: the Protector, the Woman Agnès, and the Boy.

Crimp’s bleak and precise libretto keeps us at a distance with a strange and intriguing use of third person. Most of the time the characters self-narrate. “Can you invent another woman, says the woman.” So, when first-person is used, it lands sharp as a slap. “I am Agnès. My name is Agnès.” These lines shine like signposts on her fatal run at independence, with stops along the way at rebellion and a suicidal love affair with the Boy.

Benjamin’s music seethes with tension like a painted backdrop. It favours massive, sour and rust-tinged chords, rests occasionally in suspicious, deliciously textured atmospherics, and always returns with a hobnailed blare of flute and brass to kick the characters down towards catastrophe. It is subterranean, and conductor Nicole Paiement handled its nuances with deft assurance. It was only the second time that a woman conducted at Opéra de Montréal, after Keri-Lynn Wilson in 2008.

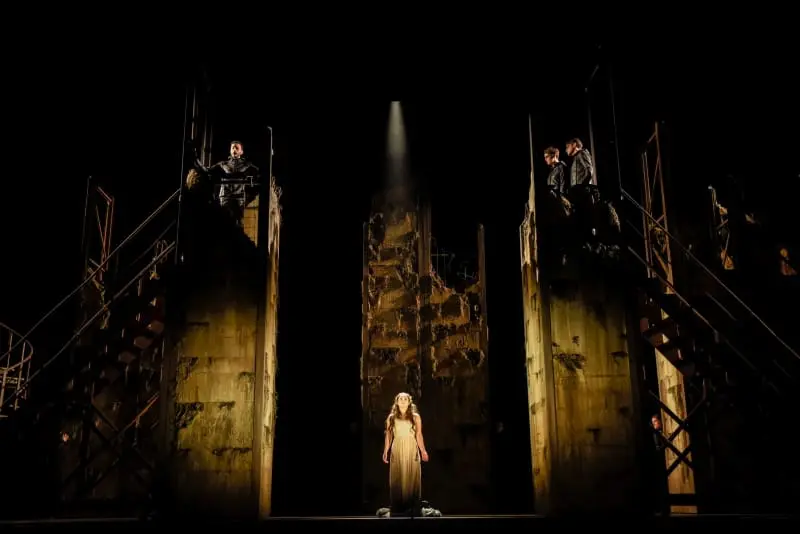

Written takes place in a medieval world of cruelty in the name of virtue, where villages are burned and babies stuck on pikes “to protect the family.” But there are also grenade lines dropped about “eight-lanes of concrete” and “car parks,” a snap back to reality that is a disorienting pleasure, like finding cumin in your ice cream and realizing that you like it. But it is harder to care about characters who wink at you. Alain Gauthier’s set embraced anachronism with splintered concrete towers topped with rebar nests and metal frames like scaffolds waiting for victims. And in almost every scene a small chorus of observing angels stood tensed in black catsuits, like bodyguards ready to brutally intervene. When two of them (mezzo-soprano Florence Bourget and tenor Jean-Michel Richer) switch roles to become Agnès’s sister Marie and her husband, they strip and change into period costume on stage. We aren’t allowed to forget that we’re watching theatre.

The Protector is Agnès’s husband and owner, a brittle icon of insecure patriarchy obsessed with control. He likes violence very much. Baritone Daniel Okulitch has never sounded better and his menacing sensuality pointed towards real characterization. Why does their perfect family not have any children? When Agnès climbs on him and demands a kiss, he rejects her, and later she accuses him of loving the Boy too. The Boy. A clueless scribe, naive enough to reveal the affair because Agnès tells him to, he becomes an angel after the Protector kills him and serves his heart to his wife. Countertenor Luigi Schifano was a poignant mix of innocence curdling into offended pride. Soprano Magali Simard-Galdès was pure-toned and exquisite in the hardest role of all, dramatically; she had to sustain Agnès’s transformation from child bride to liberated suicide in fifteen short scenes.

Magali Simard-Galdès (Agnès) and Daniel Okulitch (Protector) in Opéra de Montréal’s Written on Skin. Photo: Yves Renaud

Written on Skin is intelligent opera that tells a story of cold fascination. The characters serve their purpose and die, and it is only after they are dead that you might be troubled, when you walk away and wonder if you knew them at all.

Written on Skin continues its run at Opéra de Montréal on Jan. 28, 30 & Feb. 2.