Finally, a new opera that doesn’t get in its own way! The premiere of La Reine-Garçon on February 3 was the affirmation (that some of us badly needed) of contemporary opera’s ability to tell a compelling story. Not a story from our times, apparently that’s still an unreasonable expectation for the big companies, but even set in a 17th century Swedish court it is a story of naturalistic characters, serious and touching themes, and it takes a memorable delight in its telling. This is an opera that enjoys itself. (It runs for two more shows on February 8 and 11, 2024.)

The Opéra de Montreal and Canadian Opera Company co-production was originally announced in 2015 with a libretto by playwright Michel Marc Bouchard, whose Les Feluettes and La beauté du monde have also premiered in Montreal, and Ana Sokolović as composer, though she was later replaced without comment by Julien Bilodeau, who has worked with Bouchard before. I expected to spend more time wondering what kind of sound world Sokolović might have conjured, but it seems that the repeated Bouchard-Bilodeau pairing is paying off with greater connection and confidence between the music and text. Some moments, especially dramatic scenes in the first Act, still paled from Bilodeau’s characteristically textural sound, which can feel like it’s waiting for a singer to finish rather than propelling them, and his comfort with cheesy, throw-the-kitchen-sink-at-it emphasis at climatic moments—usually a kiss—but comic scenes and second Act drama were more musically taught and effective than anything I’ve heard from him before. Jean-Marie Zeitouni’s effectiveness in the pit shares the credit.

The story centres on how Sweden’s Queen Christine manages “an epidemic” of suitors at a time when a ruling queen was unusual, let alone an unmarried one. While actually and uncomfortably in love with Countess Ebba Sparre, she declines proposal after proposal by declaring that she’s already married to her country, which she wishes to enlighten with art and philosophy as it emerges from the Protestant-Catholic wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. The opera takes some freedoms with history but never stupidly so. The story makes more sense as it’s told with Christine credited (and blamed) for the “boring” peace, instead of getting lost in explaining that she largely inherited it. The intriguing complications of her childhood aren’t explored either, such as the contortions of how the court groomed a female heir and educated her as a boy. Leaving this out aligns her more easily with contemporary ideas of personal authenticity. Her “masculine” character is natural, maybe supported by the Chancellor’s permissiveness in helping to raise her, rather than being shaped by larger forces. So the drama comes from her struggles for personal freedom, which is a fascinating problem for an absolute monarch if you don’t think about it too hard.

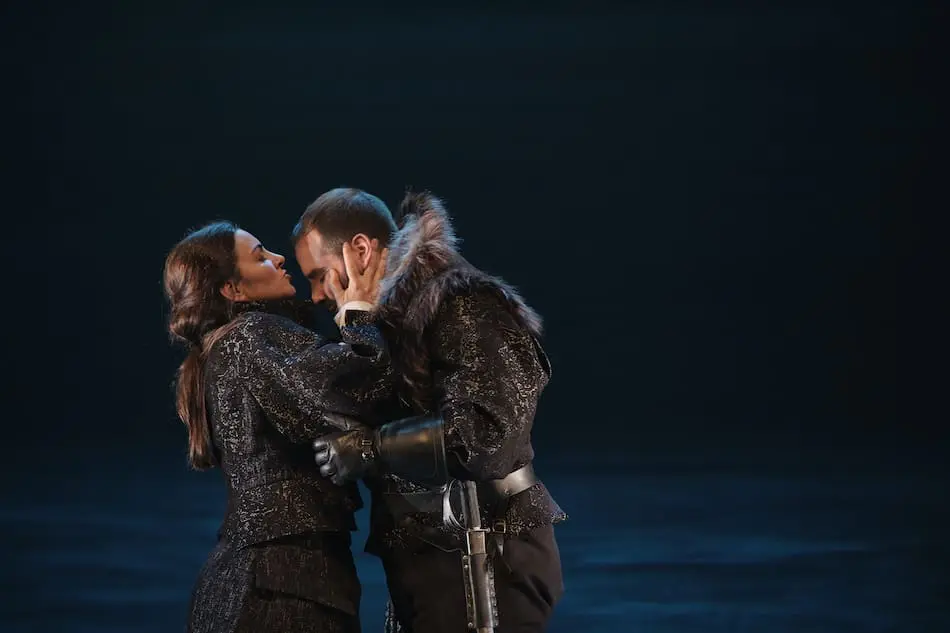

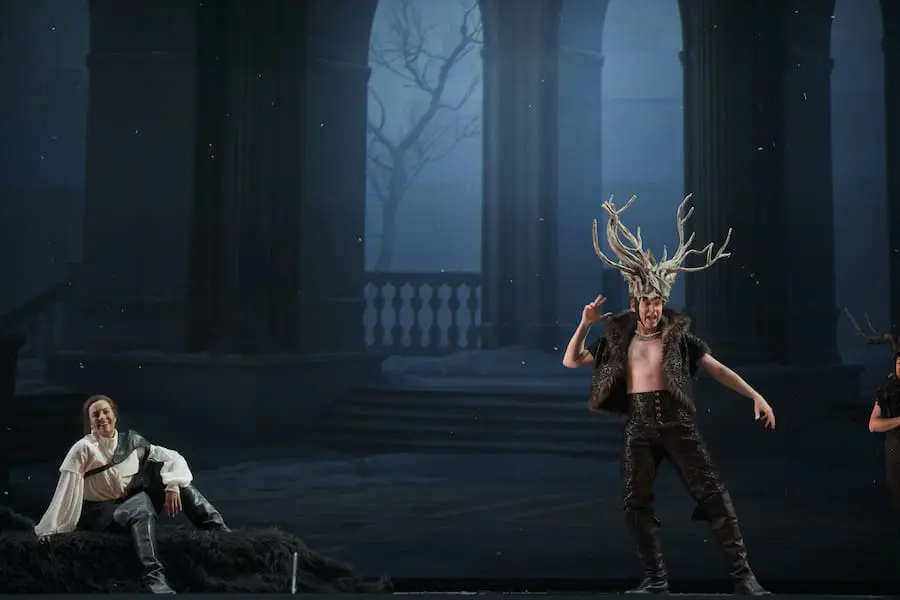

Joyce El-Khoury and Isaiah Bell © Vivienne Gaumand

Also unusual and extremely pleasing is the opera’s comfort with ambiguity, which helps its characters become usually human. The natural comparison to another recent opera with a queer character is Hadrian, which never managed to come alive. Is it court intrigue that makes it impossible for the Queen to keep a female companion, even though her father had a male “bed warmer”? Or was the Countess really unable to refuse her Queen’s affections, as she claims in one desperate scene? Both are plausible, and as in life the real reason is some mixture of them. These complications are needed to keep our interest in the opera’s abstract conceit, since La Reine-Garçon is basically a psychodrama about a negative question: how will she avoid marriage?

The Canadian cast comported themselves as expected with pleasantly unremarkable singing. Etienne Dupuis as an appropriately meat-headed Count Kustav, Daniel Okulitch as the baffled and earnest Chancellor, Eric Laporte as nerdy Descartes (one historical gloss I did regret was that the opera didn’t show the philosophe dying in Stockholm from the cold and drafty palaces, which has good comic potential though admittedly adds nothing to Christine’s story.) Joyce El-Khoury‘s Queen got stronger throughout. Often drowned out by even the most background of background music, she was best alone, or in a captivating duet with Dupuis when they repeat the same words “I love you” while meaning different people. More sparkly were Aline Kutan as Christine’s cackling and hyperbolic mother, Pascale Spinney lush and effortless as the naive Countess, and Isaiah Bell, who was delightful as the overconfident Count Horndog—pardon, Count Johan Oxenstierna.

I left feeling hopeful and excited. More of this, please.

Related Content ↘

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.