What is it about Schubert song cycles that attracts the Regie gang? In recent years Christof Loy, William Kentridge, and David Alden have all had a go at Winterreise, whose coherent narrative plausibly invites theatrical treatment. Now Claus Guth has tackled Schwanengesang, which doesn’t—it’s a posthumously assembled collection of songs telling no overall tale—in a ninety-minute staging called Doppelganger. Commissioned by New York’s Park Avenue Armory for presentation in its 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall, and tailored to the ever-questing talents of tenor Jonas Kaufmann, it filled the massive space as well as anything I’ve seen there.

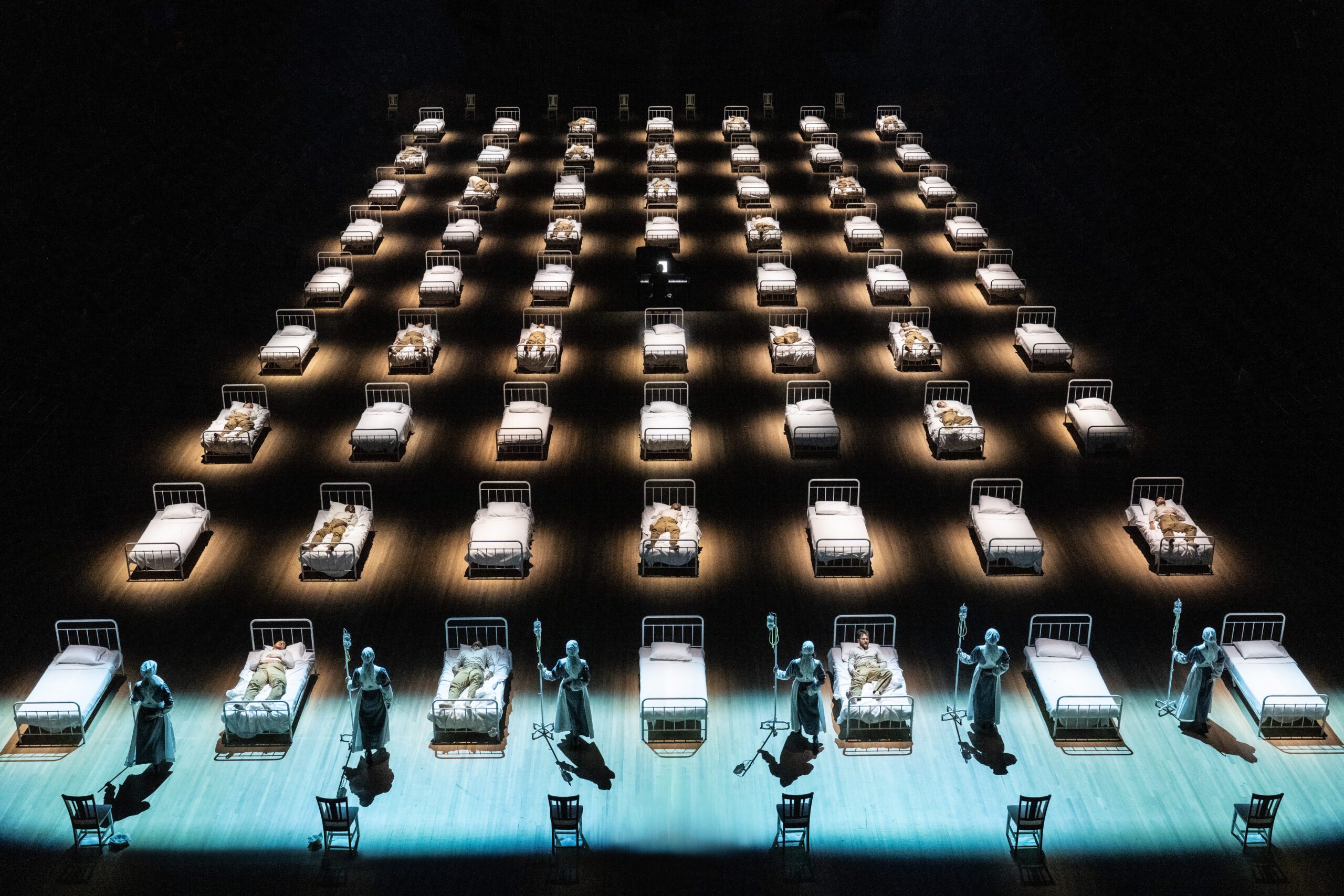

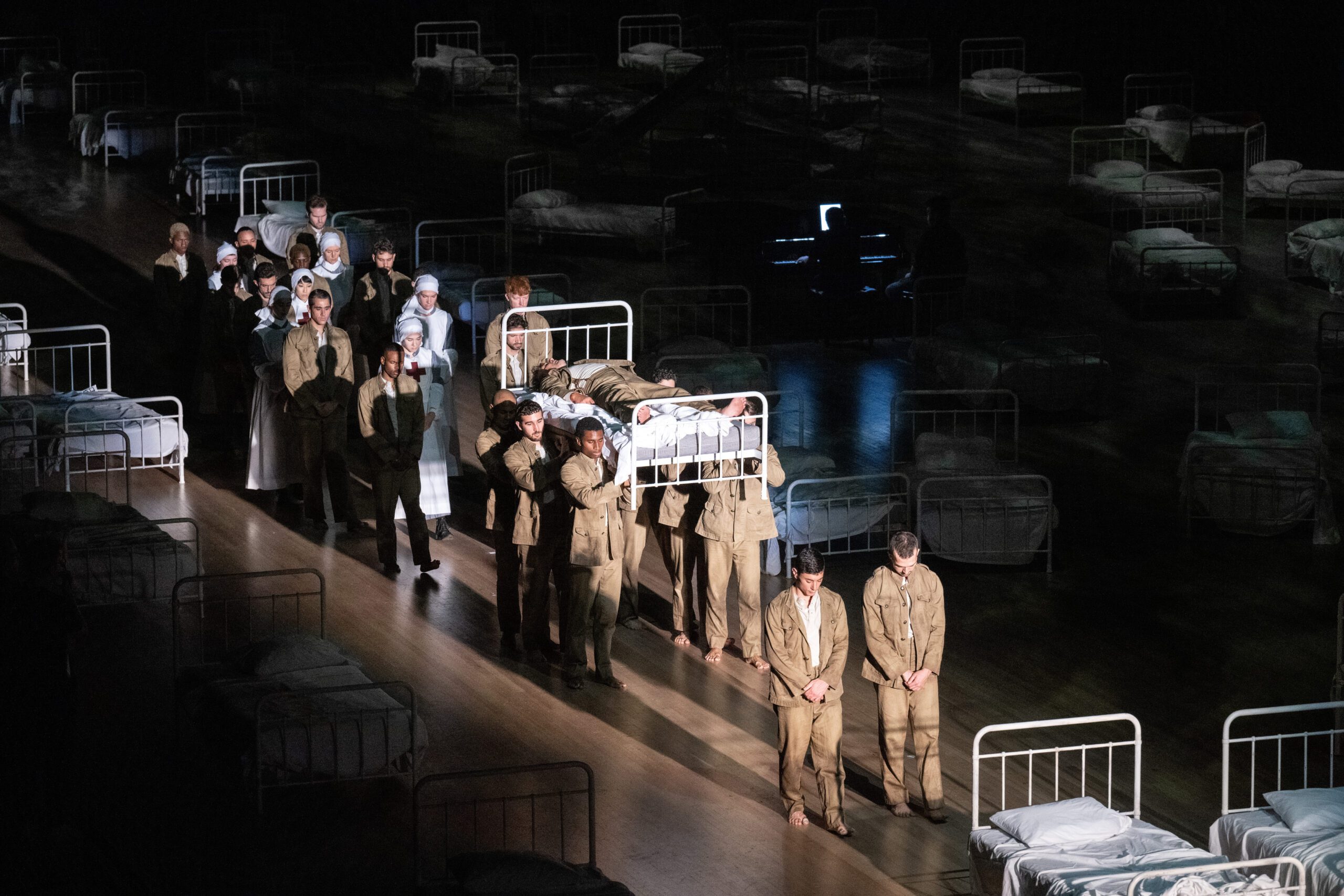

The audience—occupying, length-wise, the north and south sides of the hall—enters to ominously ambient sound and to the sight, in Michael Levine’s typically spare and striking design, of row upon row of old-fashioned metal-frame hospital beds, a third of of them occupied by sometimes still, sometimes restless recumbent figures; in the center sits a grand piano. That first experience of Levine’s setting afforded, for me, the production’s most memorable moment. Once Helmut Deutsch, having unabtrusively taken his place at the keyboard, began to play, unamplified, the ominous opening bars of “Kriegers Ahnung” (traditionally the collection’s second song, but here the first), and Kaufmann rose from one of the dozens of beds and began to sing, amplified, the misgivings set in. Was the star tenor lip-syncing?, I wondered, so disjunct were the singer and the sound; but no, he eventually stood six feet in front of me and I could hear that he wasn’t.

A vague plot began to emerge, with twenty-two male patients, plus Kaufmann, tended to by six female nurses, their costumes evoking the “Great War” of 1914–18. Mathis Nitschke’s electronic interludes glowered and growled between songs while Sommer Ulrickson’s “movement direction” put the nimble ensemble through their often effective, more often distracting stylized paces. Between the eight songs with texts by Ludwig Rellstab and the six settings of Heinrich Heine, Deutsch played, beautifully, the Andante sostenuto from Schubert’s final piano sonata. By that time, though, the title of another Schubert song was popping into my head: “Wohin?” (from Die schöne Müllerin): just where, I was asking of Guth’s show, as the poet asks of the babbling brook, are you going? And when the title song rolled round, the view from beyond the loudly opened-wide service door from which Kaufmann’s doppelganger emerged wasn’t a World War I–era battlescape or death’s white light but twenty-first-century Lexington Avenue, taxicabs sloshing by on a rainy Thursday night. That’s where Guth was taking me?

Park Avenue Armory’s production of Doppelganger , 2023 Ⓒ Monika Rittershaus, Park Avenue Armory

To be fair, his show wasn’t billed as Schwanengesang but as Doppelganger (no umlauts), and its intent wasn’t to offer a straightforward rendering of Schubert’s songs. There were arresting moments, no doubt—the funeral cortege, for one, with a prone but singing Kaufmann carried aloft on his bed. But I wish this very concept-friendly German director, whose work I’ve often admired, had made his American debut with a real opera and not with this padded-out (fifty minutes extended to ninety) “event.”

As far as I could tell, the hardworking, barefoot, handsomely grizzled Kaufmann sounded in good form; and he set a happy recent record, I believe, by singing five consecutive performances without a single cancellation. I was glad to encounter him live for the first time in many a year. If only he’d been singing, and Deutsch playing, straightforward Schubert on the stage of Carnegie Hall!

In a not dissimilar vein, a ballet set to the Verdi Requiem by German choreographer Christian Spuck has been making the rounds of European houses; it’s even taken a trip Down Under. I was happy, though, that for the second night of its new season—the night before I saw the Armory’s final Doppelganger—the Metropolitan Opera was offering a Verdi Requiem whose full orchestra, chorus, four soloists, and conductor admirably filled its stage without any trace of a superimposed staging. This was, in fact, the biggest crowd I’ve ever seen amassed up there, not excluding the still-gasp-inducing two-tiered Parisian street scene of Zeffirelli’s beloved vintage La Bohème. And the sound matched the sight: it was a grand noise they all made, on a massive scale; but under the direction of a clearly engrossed Yannick Nézet-Séguin (in atypically subdued attire) there was plenty of detail and dynamic variety to relish.

The soloists were uneven: bass Dmitry Belosselskiy was imposingly resonant; tenor Matthew Polenzani sounded below his best form; and soprano Leah Hawkins, with a lushly ear-catching basic timbre, too often let her soft singing harden and her long phrases wilt. Best of the four was Karen Cargill, her fine dark mezzo-soprano in expert control of a wide dynamic range. The orchestra played brilliantly. But pride of place, I thought, went to the chorus, which raised the roof when it had to but launched the opening “Requiem aeternam” with hushed reverence. Chorus master Donald Palumbo, whose valedictory season this is, got his share of cheers at evening’s end, and no one on the full-to-the-brim stage deserved them more.

Related Content ⬇

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.