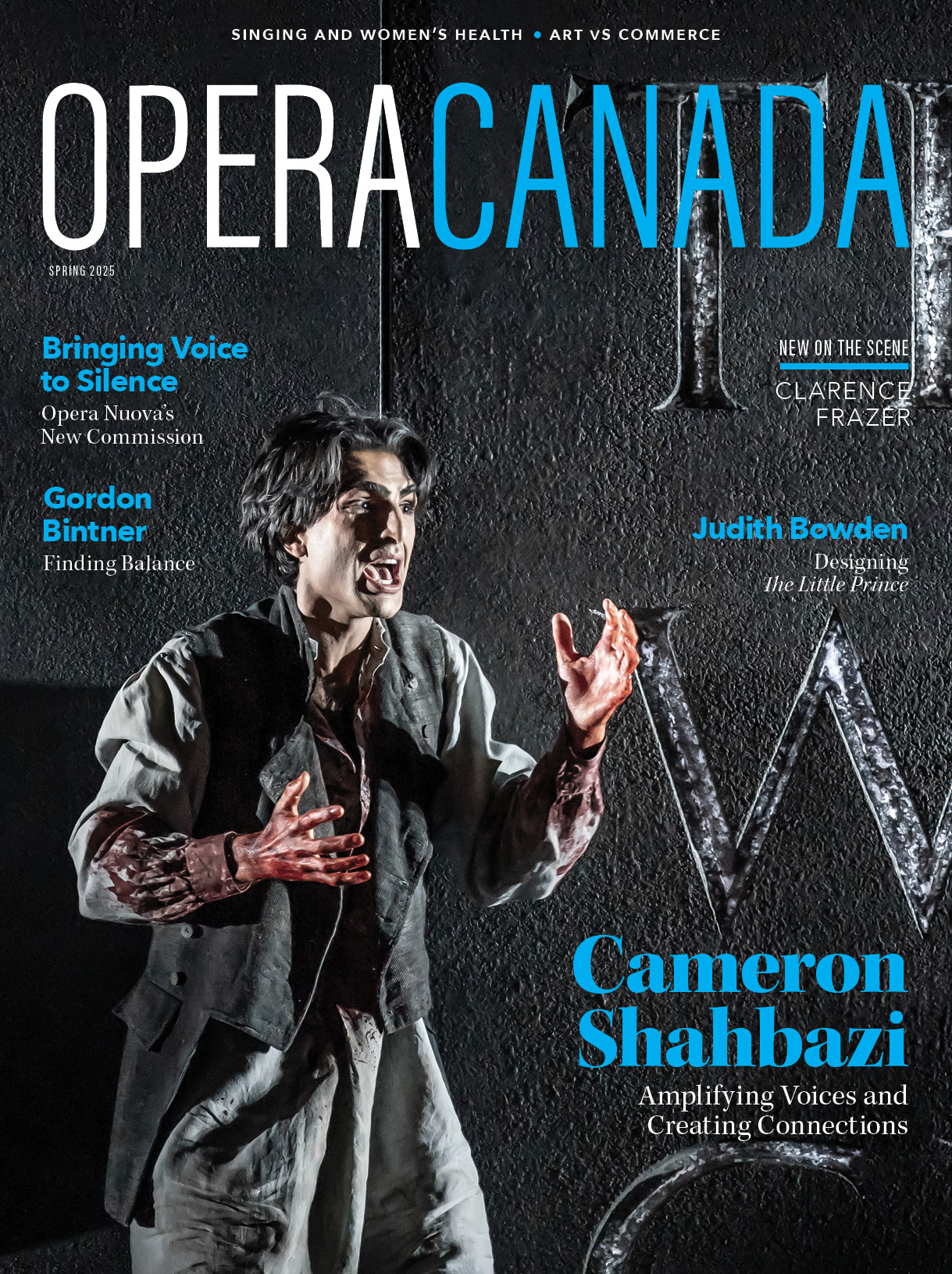

As an opera, Missing is under-written. As an important piece of theatre that builds over its short 80 minutes to a shatteringly emotional conclusion, this Pacific Opera Victoria production is something every Canadian should see.

Co-commissioned by Pacific Opera Victoria and City Opera Vancouver, Missing opened first at Vancouver’s traditional, proscenium arch York Theatre on Nov. 3. It then moved to a sold-out run at POV’s Baumann Centre headquarters, a more intimate space where the audience sits flat on the floor, practically face-to-face with the performers on their low platform. We can hear them breathe; they can see our eyes and know intimately how their performance is affecting us.

The Highway of Tears

POV clearly worked closely with the Indigenous community to ensure the production reflected and respected Indigenous culture and values. The centre smelled of burning grass as we entered. Local elder Bradley Dick introduced himself and his ancestry in his first language, then in English, and offered us a traditional song before the opera began. Smudging and cedar brushing were available after the performance for anyone who felt the need to soothe their soul. And these details were important. It made sure that we, as a predominantly white audience, felt welcomed even though, as the libretto by Métis-Dene writer/actor Marie Clements made clear, the Indigenous community has little reason to love us.

Missing begins along the Highway of Tears, the 720-kilometre stretch of Highway 16 in northern BC between Prince George and Prince Rupert, where an unknown number of Aboriginal women and girls (the police say 19, but Aboriginal communities place it at over 40) have been murdered or have disappeared since 1969. Very few of their cases have been solved. Joined with other cases across Canada, the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls reaches over a thousand.

The Native Girl

In this story, a young white woman named Ava (soprano Caitlin Wood) is badly injured in a car crash. Thrown into a tree, she sees the body of another young woman, known only as Native Girl (compelling Métis soprano Melody Courage), on the ground below. Their eyes meet and they connect profoundly. Native Girl keeps reappearing in Ava’s life, reflected in windows and mirrors; Ava begins to work with UBC professor Dr. Ruth Wilson (strong First Nations mezzo Marion Newman) to learn the Gitxsan language and culture; she marries white boyfriend Devon (Kaden Forsberg) in a Gitxsan ceremony; Ava witnesses Native Girl’s murder in a dream.

Weaving in and out of this narrative is a second, involving Native Girl’s mother (Coast Salish mezzo Rose-Ellen Nichols) and brother (bass-baritone Clarence Logan, whose mother is from Moosomin First Nations). Native Mother’s grief is so deep, much of the time she can only sit and mourn. Native Girl’s brother feels guilty because he was not able to protect his sister.

All of the roles were well sung, including the small, thankless part of Jess (mezzo Heather Molloy), a law school friend of Ava’s who embodies everything that is hateful about unthinking prejudice. They were also all meticulously performed under the direction of Peter Hinton, although the technique of having characters pace slowly from side to side, effective early on to give body to the weight of grief experienced by the Indigenous community, felt slightly overdone by the end. But that over-repetition became noticeable only because the singers simply did not have enough to sing.

The opera

The musical intention of Clements and composer Brian Current may have been to avoid the usual arias, duets and choruses appearing at regular intervals to break up the recitative. But there isn’t, in fact, that much recitative and, instead of being an opera, this feels more like a chamber music suite (ably performed by a seven-member ensemble under Native American conductor Timothy Long), with some singing here and there. Current’s orchestral language is spare but gripping, and would be interesting to listen to with no singing at all, but the few times the characters were given the opportunity to express themselves in aria or ensemble form, his work (and the libretto) lifted to the very nearly sublime. Native Mother’s one keening song to her lost child, in Gitxsan, was both a universal cry of anguish, and a searing look into her damaged soul.

Missing needs more of that: more libretto, more opportunity for all of the characters to tell their stories and become three-dimensional. At the same time though, its dramatic and visual power—helped by a stunning set that includes a giant, skeletal rib cage on the floor and haunting projections on the scrim covering the bones of a longhouse, by Euro/Omushkego Cree artist Andy Moro—and the simple force of the tragedy the Indigenous community continues to face make this production a must-see, for all Canadians.