Innocence starts with a wedding toast that seems gloomy. The eerie, haunting overture offers clues. The Bride, we soon learn, does not know that her Bridegroom’s brother is a mass murderer of ten years past. The audience discovers this crime’s full nature only with unfolding action. And she only towards the end. But this secret contains other secrets that explode into a huge, final dramatic reversal of the kind found in classical tragedy.

Kaija Saariaho and her brilliant librettist Sofi Oksanen built their potent one-act opera in this form, explicitly in view of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck and Richard Strauss’s Elektra. I suspect also Arnold Schönberg’s Erwartung—all in atonal idioms. Conductor Clément Mao-Takacs led the complex score with authority and a subdued taste, perhaps lacking a final degree of intensity. He worked closely with Saariaho and with her son, Aleksi Barriére, who composed the spoken lines. San Francisco, as one of the commissioning companies, has done itself proud with this U.S. premier.

The numerous scenes unfold in continuous flow upon a huge two-level rotating cube that fills the stage (direction by Simon Stone, revival by Louise Bakker). This dynamic cube not only supports the story, but becomes part of it. For, different from typical rotating sets, where the perhaps three scenes continually reappear, this cube presents numerous rooms as it moves around, sometimes familiar, sometimes new. (The army of stage hands that managed it got the first curtain call.) The cube, designed by Chloe Lamford, with costumes by Mel Page, glowered as if in film noir under lighting by James Farncombe and sound by Timo Kurkikangas.

This impressive machinery enables the cinematic flow of Innocence. This flow is central to the work’s unrelenting power. Since the cast is fully miked and made up both of singers and actors, the orchestra can seem to be sounding an accompanying score as if in film. Saariaho composed the vocal line around the many different languages of the players.

They never break into aria, or even arioso in the manner of, say, Monteverdi or Wagner. As with many contemporary opera composers, we get varied lines that never depart from accompanied recitative. Although percussion and brass heavy, the orchestra often emits floating sounds reminiscent of horror films, punctured by huge outbursts at potent moments or breaks almost like entr’actes. An underlying tension builds to almost unbearable levels through 100 minutes.

The past crime is a shooting at an International School, in which ten students and a teacher died under the gun of the brother. We see him being bullied in this production, but not the gunfire that litters the scene with dead, dying, and terrified students. These moments interlace with the wedding and with others representing the survivors and their memories within an intricate tapestry of guilt and trauma (Can I stand with my back to the door of the church when I get married?). An invisible wordless chorus reminiscent of Debussy or Ravel reinforces the ghostly atmosphere, breaking out at the end and before to chant the names of the dead. Time approaches a quantum continuum.

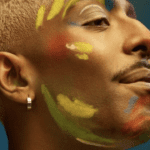

Photo Credit: © Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

The focus of emotional energy is a waitress, the mother of a dead student named Markéta and the random replacement helper serving the wedding for a sick colleague. Soon, seeing that the groom’s brother murdered Markéta, The Waitress’s tension builds to confrontations with family members. Her burning anger centers some of the work’s most intense moments. Ruxandra Donose sang with real mezzo power in the role, and she is a fine actress, but did not project the obsessed demonic fury truly demanded by the part.

If the Waitress is the central living character, Markéta is her ghost doppelgager, and the only dead student who sings, although the living actor students sometimes engage in stylized speech. Saariaho wrote the girl’s part specifically for a singer of Finno-Ugric songs named Vilma Jää. Her very high nasal tones live in a magical realm outside usual singing–be it popular or operatic. In the end she implores her mother to return to a life beyond obsession.

The school’s surviving Teacher leads the mourners. Unable to focus after her trauma, she relives it at her every appearance, breaking late into a long, quite chilling passage of Sprechstimme. Lucy Shelton, who originated the part and for whom it was written, assumed tragic dimensions on behalf of all present.

Canadian Claire de Sévigné made her San Francisco debut as the groom’s emotionally cornered mother, who had wished to invite the brother to the wedding. This part is large, dramatically vital, and written at an extremely high soprano tessitura that challenges vocal expression. De Sévigné compensated with fine acting, while discharging the vocal line with precision and tonal beauty. (In a parallel summer production of The Magic Flute, Canadian Olivia Smith really was first voice in the surprisingly present role of First Lady.)

Rod Gilfry shone in the difficult role of the more conventional husband, who believes that all will turn out if properly smoothed over. Lilian Farahani (the original Bride) sang with power and insight upon learning of the brother and expressing her sustained love for the Bridegroom, Tuomas, (the convincing tenor Miles Mykkanen). With plenty of guilt to go around, a family priest who early suspected the brother (Kristinn Sigmundsson) and a surviving student named Lilly (Beate Mordal) who hid in a closet and locked out others share in the catastrophe. Iris (the tall and commanding actress, Julie Hega) becomes the most prominent speaking student in Innocence. She reveals at the climax and tragic reversal, along with Tuomas, that they planned the shooting with his brother and silently retreated in last minute doubt at the entry to the school. The secret within the secret tears at our overwhelmed hearts. The audience erupted.

Related Content ↘

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.