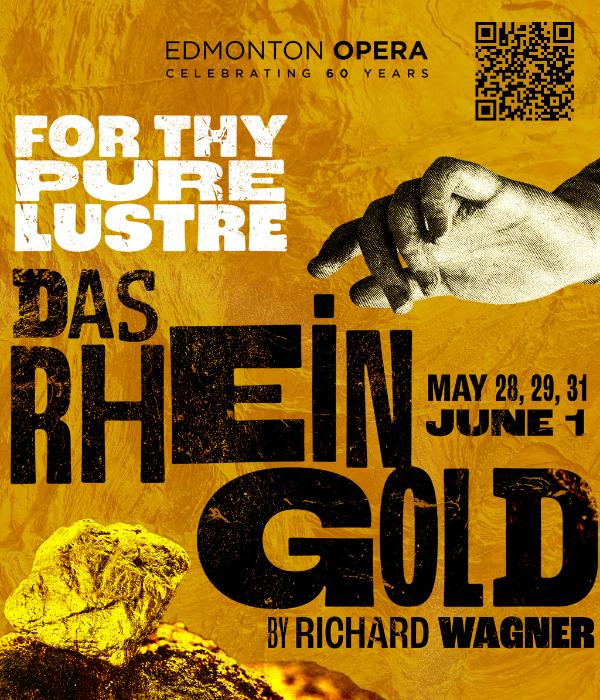

Wajdi Mouawad’s much anticipated production of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio made its Toronto debut last night, having first premiered at Opéra de Lyon in 2016. In his program notes, the Lebanese-Canadian writer and director makes it clear his vision would go far beyond the original 18th-century text’s “caricature, or casual racism” of Muslim culture to “approach the text in a new way and see a different point of view on these issues.”

Thankfully then, there is no trace of the traditional racist portrayal of Osmin, the harem’s guard, as a violent, mustachioed, turbaned terror. Mouawad reframes the original opera as a flashback—the production opens at a party celebrating Konstanze and Blondes’ homecoming to Europe after their incarceration in the East. Back in England, they converse with their respective beaus, Belmonte and Pedrillo, about their time in Bassa Selim’s harem, and urge these ‘enlightened’ European men to consider the possibility their Eastern sojourn was not all bad. Taken by itself, this vision works for the most part, making its points along the way not only about 18th-century (and by extension, present-day) Islamophobia but also, patriarchal attitudes towards women (which also unfortunately still loom large in the current political climate).

(l-r) Jane Archibald as Konstanze, Mauro Peter as Belmonte, Owen McCausland as Pedrillo and Claire de Sévigné as Blonde in the Canadian Opera Company’s The Abduction from the Seraglio. Photo: Michael Cooper

Text and music clash in The Abduction from the Seraglio

However, the intersection of this radical re-visioning with the original text creates some real problems. As much as it is a relief to be done with a racist portrayal of Osmin, the music Mozart composed for him does not change—it is still full of lively, percussive rhythms; bright instrumentation and rapid patter. Bass Goran Jurić observed all of this with robust, resonant tone and delightfully colourful word painting, but the dour directorial concept straitjacketed his portrayal, leaving us a little discombobulated.

The object of his affection, Blonde (soprano Claire de Sévigné), is a character drawn directly from the opera buffa tradition. However, Mouawad’s concept drained her of any of these comic origins and the much-needed contrast she provides to the ‘serious’ couple, Konstanze and Belmonte. That Sévigné still managed to win us over had more to do with her perfectly-placed high soprano and naturally sunny stage manner which trumped the surrounding gloom.

Beyond the past/present framing device, Mouawad goes even further to introduce elements into the ‘past’ (the opera proper) which are entirely of his own invention. Osmin and Blondes’ relationship has apparently gone far beyond the usual playful sparring—Mouawad makes it clear they have been sleeping together and she is pregnant with a child who will be returned to its father after she returns to England. In their comic duet, despite text indicating Blonde’s protestations urging Osmin to essentially ‘get lost’, both singers lay down on stage canoodling. These situations were no doubt invented to signal a much closer relationship than is usually the case, but is so far removed from the original text that one has to question, why bother staging Abduction at all—perhaps an entirely new piece would have served Mouawad’s purposes better.

(foreground) Jane Archibald as Konstanze and Raphael Weinstock as Bassa Selim in the Canadian Opera Company’s The Abduction from the Seraglio. Photo: Michael Cooper

Swiss tenor impresses

There now seems to exist a tired cliché in opera criticism of “the production didn’t work…but the singing was great” which I am about to invoke again here. The vocal discovery of the evening was debuting Swiss tenor Mauro Peter as Belmonte. In the realm of Mozart tenors, he possesses a uniquely dark, full middle range with a very heady, falsetto-y top that nevertheless projects clearly into the hall. He immersed himself into the proscribed portrayal, even when asked to spar (to what purpose?) with one of the bald-wigged eunuchs during the aria “Ich baue ganz”—a coloratura minefield often cut from performances—which Peter nevertheless handled masterfully.

Jane Archibald’s middle register is now much larger and darker than when she first appeared at the COC as Zerbinetta in 2011 but she still maintains a well-integrated upper range, despite some sharpness in this area in her opening aria. The conclusion to Konstanze’s great lament, “Traurigkeit” felt like the one moment in the evening when all the elements came together—music, words, staging (she was crumpled in a heap)—to evince palpable emotion.

Owen McCausland’s Pedrillo was sung with much fuller, heroic tone than one usually hears for this ‘comic’ sidekick—his fearless commitment to voice and action continue to evolve and impress. Israeli actor Raphael Weinstock created a wonderfully nuanced Bassa Selim—a role that interestingly, is hardly altered in this conception.

Scintillating orchestra for Abduction

COC Music Director Johannes Debus was back after an absence this fall and led a slightly slimmed-down COC Orchestra with great period style. It was another of this production’s incongruities that the sprightly, bright, scintillating sounds emanating from the pit seemed so at odds with much of what was happening on stage.

“What do you love most about opera?”

Several times, Mouawad allows the characters to speechify about similarities between societal norms in the West and the East. While enlightening, these moments feel unnecessarily ‘tacked-on’, given how thoroughly he has otherwise delineated his ideas. At intermission, a young woman attending her first opera boldly approached me asking “What do you love most about opera?” She explained she was not enjoying her first taste of it at all. Taken aback, I took a moment to recover and replied “When the music and words come together in such a way that I have a visceral, emotional reaction.” Unfortunately, this Abduction didn’t provide much of that, instead substituting a well-argued think piece which failed to function as theatre.