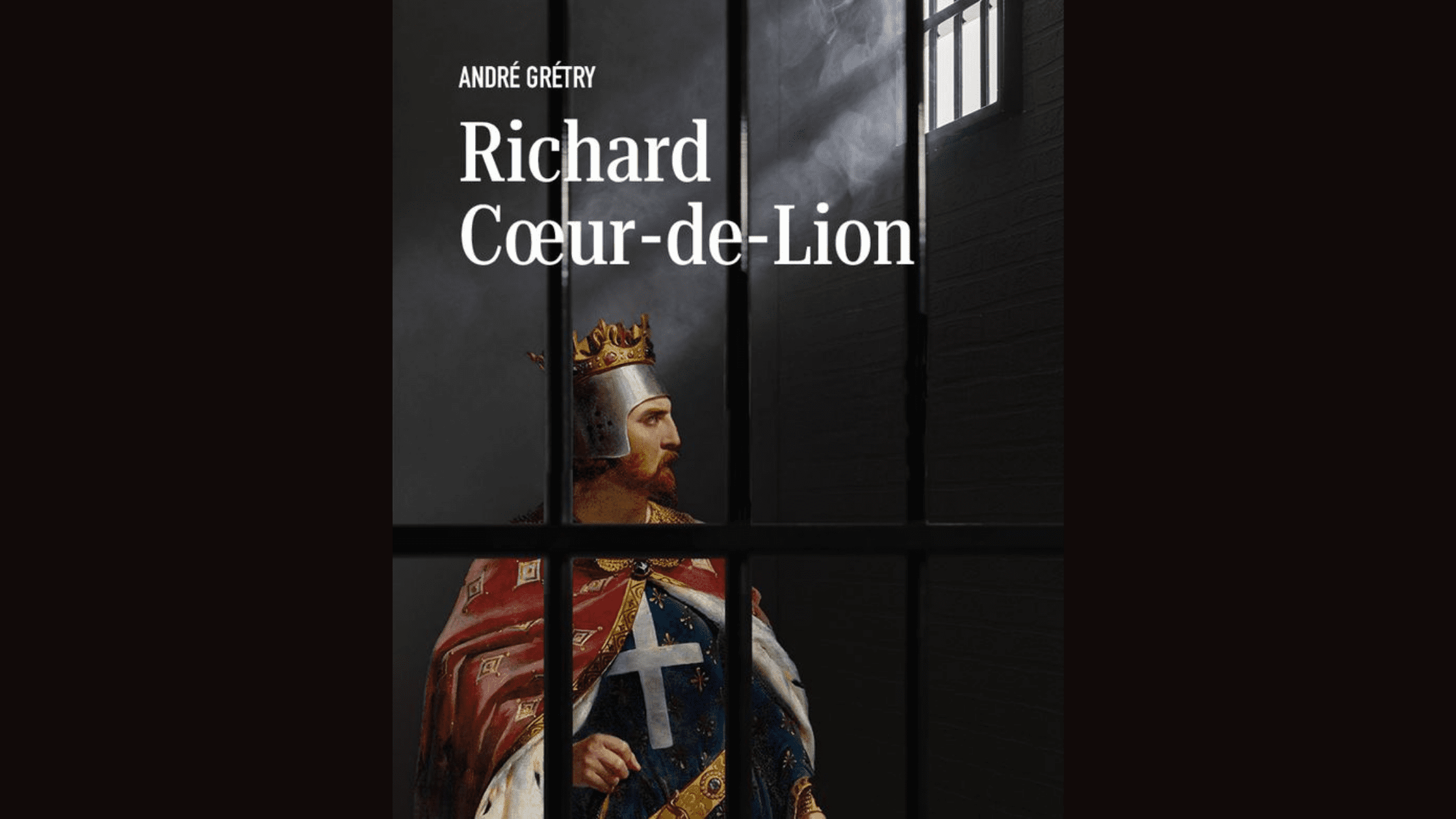

Just a few years after the 1784 première of André Grétry’s Richard Coeur-de-Lion at the Salle Favart in Paris, the ripple effects of the French Revolution would be felt throughout the opera world. Championed by the monarchy under the patronage of Marie Antoinette, the genre had a complex journey through regime change. Its overt themes of fidelity to the “abandoned” monarch were ideal fodder for anti-revolutionary conservatives, and as an opera emblematic of the last years of the ancien régime, both Richard and Grétry’s status struggled to survive through the 19th century.

As far as we know, Richard has never been staged in Canada, making Saturday’s performance from Opera in Concert (OiC) an exciting event. In presenting this foundational work of opéra comique, OiC fulfilled with great success its mandate to bring lesser-known repertoire to Toronto audiences. “Rarely heard” operas sometimes are better off staying that way, but Grétry’s drama is emphatically not one of these. An early example of the “rescue opera” (the most well-known of which to modern audiences is Beethoven’s Fidelio), Richard has the necessary ingredients of sentimentality, disguise, imprisonment and escape. But so too is it defined by comic and pastoral tropes topped with a dusting of 12th-century Crusade history – an idiosyncratic mix which the cast and direction from OiC brought to life with vitality and wit.

Opera might have always been something of a grand affair, but it doesn’t always need to be big. The rather eccentric repertoire of 18th-century opéra comique can benefit from more modest settings. The relaxed environs of Trinity St-Paul’s Centre are well-suited to OiC’s condensed two-act version of Richard, presented on an intimate, stripped-back scale whose best feature is the immediacy of connection established between performers and spectators. For example, spoken dialogue, a defining feature of opéra comique, was presented in English, a sensible choice with much precedence. The translation and delivery came through especially well when sitting mere feet from the performers, allowing the humorous improbability of the drama to be communicated effectively, assisted by the comic timing and thoughtful acting choices of the cast.

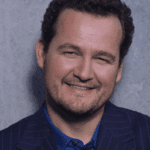

The King holds the title, but the star of the show is undoubtedly Blondel, squire to Richard, sung and acted with remarkable aplomb by Yanik Gosselin. A clear, powerful voice with careful attention to tonal nuances, his performance was that of a true French lyrical tenor, most notably in the opera’s most famous air “Une fièvre brûlante.” Leaning into the comic quirks of the drama, his acting talents were as promising as his vocal.

Though unfortunately afflicted with illness, Colin Ainsworth nevertheless was ideal to take on the figurehead role. While his principal aria suffered somewhat in lower registers, Ainsworth under the weather is no less a delight to hear, and he brought the requisite stately presence of the venerated monarch to the stage. The imprisoned King, in fact, rarely appears, and the bulk of the drama concerns Blondel’s rescue efforts (plus a few love intrigues along the way).

Colin Ainsworth, Yanik Gosselin and Nicole Katerberg

So too is the case for Richard’s fiancée, Marguerite Countess of Flanders (a wholly ahistorical character, incidentally), who is granted only a few appearances. More’s the pity for us: soprano Nicole Katerberg, taking on her second role for OiC this year, was a triumph. With a warm but formidable tone, she brought a maturity of voice and stage presence that is quite striking for this point in her career.

Several smaller roles similarly saw a delightful array of young talent. Acting as Blondel’s guide, mezzo-soprano Madeline Cooper took on the trouser role of Antonio with great success. She offered a lighter tone within a clear and strong voice that is ideally suited to the character, projecting a perfect mix of insouciance, confidence and amorous desperation à la Cherubino. A remarkably rich bass in Joseph Ernst, meanwhile, brought a welcome gravitas to the role of English exile Sir Williams, while Alice Macgregor shone as his daughter Laurette, the frustrated ingenue.

The chorus brought the vigorous energy needed for a concert performance, especially powerful when placed in the side balcony, a clever choice that maximized the hall’s acoustics to make 11 voices sound like 50. OiC occupies a valuable place in providing a platform for emerging singers to gain professional operatic experience, and I came away hoping to hear a lot more from all of them.

A few tweaks could have refined the performance considerably: the grand piano sitting centre stage resulted in some awkward choreography and a confusing acoustic effect of overwhelming the singers in several passages. While I longed for a harpsichord and a small chamber ensemble, Suzy Smith performed superbly on the piano, in touch with all the expressivity of the singers. I could see the logic of placing violinist Soltan Mammadova in the balcony to provide Blondel’s violin playing, but issues of intonation and precision marred the delivery somewhat, and the distance ultimately hindered the effect.

Of course, much of this comes down to financial practicalities and available resources, and I was glad to hear general director Guillermo Silva-Marin announce that OiC’s new sponsor, the Azrieli Foundation, is providing seed money to help the company revive plans for an orchestral component. A little will go a long way in this regard. There is a strong niche for chamber opera in the current performance landscape, and OiC continues to prove that there’s space and desire for centuries-old drama alongside contemporary premieres.

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.