The music came to a sudden stop and the curtain fell onto the stage with mechanical precision. As the choir hummed, a heart-rate monitor blared out a sinister flat-line and for a moment I thought I’d died. Sadly though I was still very much alive. When the lights snapped on for intermission and the audience wandered along the aisles in confused somnambulism, I felt as though a hundred inner-voices expressed the same desperate cry:

“Oh god, is there really another hour of this?”

Pink Floyd’s The Wall is the brainchild of bassist Roger Waters. It is widely regarded as one of the greatest concept albums of all time, exploring nuanced, scathing caricatures of post-imperial Britain and the way trauma breeds depression and anger. Another Brick in the Wall by contrast is an interminable slog of an opera, desperately grasping at any sort of point-of-view or depth and coming up pathetically short.

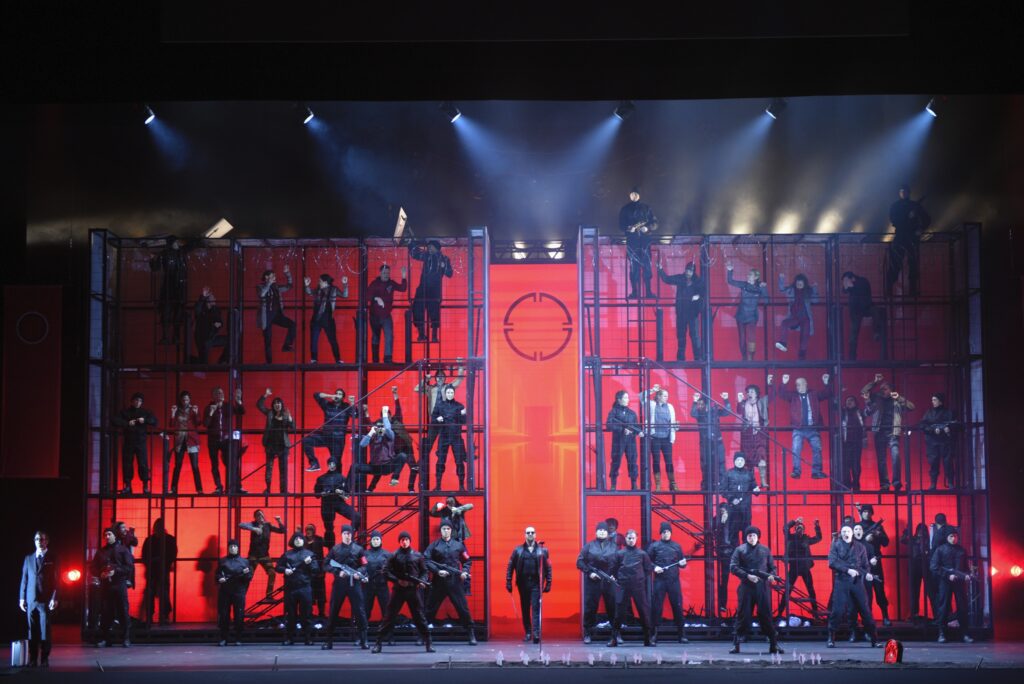

Let’s get the good out of the way before I burst a blood vessel. Despite how my cold, black heart might feel, there is a lot to praise. Kudos to Stéphane Roy and Étienne Boucher, the staging and lighting really are spectacular. Two enormous, white bricks rise to the ceiling and glide along the stage, opening and closing as befitting the metaphor of the wall. Videos by Johnny Ranger are projected onto these two slabs, creating a visual wonderland alongside flashing stage lights. Everything from the universe to empty cityscapes is projected onto the screen, sculpting the story’s cold, detached world. The walls eventually rotate to reveal enormous labyrinths of staircases and cages during the story’s Fascistic fantasy sequence, constituting the last sincere feeling of wonder I felt for the duration of the show.

Then there are, of course, the performers. Never have singers been given so much, yet so little to work with. Fresh off a run in Cincinnati, Nathan Keoughan’s Pink was a trooper, forging forward throughout the show. His explosive highs boomed into the audience and evoked the original album’s mean-spirited ennui well. France Bellemare, Jean-Michel Richer, and Caroline Bleau were also effectively emotive as The Mother, The Father, and The Woman respectively. They sang beautifully, or, at least, I assume they did. I couldn’t hear a damn thing!

Yes, Meridian Hall (formerly Sony Centre) is a fickle beast. Its cavernous interior created a black hole that swallowed all sound. The orchestra (who also suffered the beast’s merciless appetite) however is not blameless, and did equal work to drown out the voices. Act II offered a little respite as singers warmed up and more care was given to their audibility, but Richer’s aria, staged as a seminal emotional turning point, may as well have been sung underwater.

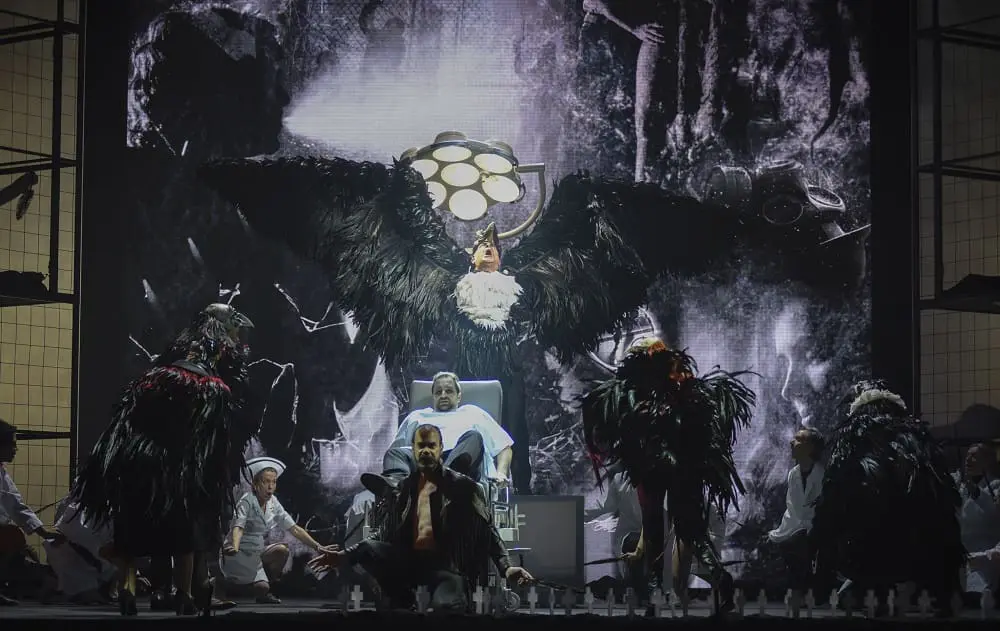

This would not have been as egregious if the music offered any excitement. Alas, the composition was dry and empty. Gone is any of the variety, funk, or tenderness of the album. Instead we get auditory wallpaper reminiscent of a subpar Marvel movie score. When Pink is hospitalized we are offered a synth-wave-laced instrumentation and visuals evoking 2001: A Space Odyssey, which set a high bar early on. But save for some playful string-plucking, the score quickly devolves into a repetitive, monotonous dramatic register; as monolithic and empty as the titular wall, crushing everyone on stage.

And really, there is a subtle disregard displayed toward the singers and the orchestra itself. No program was handed out, no cast-list to be seen on the show’s website. Another Brick in the Wall reduces the actual people on stage to cogs, all in the service of their super deep and important tale of individuality.

And what a tale! Another Brick in the Wall borrows the album’s basic narrative: Pink is a rock star haunted by the death of his father, his overbearing mother, and his abusive school system. He constructs a psychological wall between himself and the world, describing each trauma as a brick. After a rage-fueled bender precipitated by his wife leaving him, he fantasizes himself as a genocidal dictator. Horrified by his hatred, he puts himself on trial, reconciling his trauma and tearing down the wall.

The libretto is transcribed from the album’s lyrics, and comes across as gibberish. The words, stripped of context and occasional irony, are nonsense and clumsily clash with the already paper-thin characters. The Father sings “The Thin Ice” lovingly to baby Pink in a well performed scene. But why a father would threaten his child with the icy blackness of existential abyss is beyond me. It ties in with the bleak aesthetic of the world and the ideas the story lazily toys with, but it tells us nothing about this character. Or maybe he just kind of hates his kid, what do I know?

Speaking of ideas, the themes are all so smug and pretentious. Pink’s inner-child wanders around, planting crosses sullenly and reducing Pink’s trauma to that all too trite theme of lost innocence. Gone is any self-awareness or sardonic sense of humour. Everything is dark and serious and deeeeeep and leaves the story laughably delusional. Even the fascist sequence comes across as goofy. “Look how edgy we are,” says the show even as its jackboot soldiers look like they hopped off an SNL skit. To Another Brick’s credit, this does culminate in a moment so cheesy and on-the-nose it almost comes back around to being great: Child Pink, played by Vittorio Campenelli and Eliott Plamondon, goose-steps onto the stage clad in riot gear and prepares to execute the spectre of Pink’s dead father, all while political prisoners chant in unison. Wow. So deep. So thought-provoking. So psychological.

Ugh.

Really, what sinks the show is that the story says so little while convincing itself of its profundity. What’s more, moments of genuine humanity are scattered throughout. Moments like Stéphanie Pothier’s Vera Lynn, who extols an end to war in a beautiful swell alongside the consistently lovely chorus. Moments like Pink’s confrontation with The Woman, an interaction freed of overbearing themes that allows the actors’ humanity to do the talking. But these moments are few and far between because these aren’t characters: they are symbols stripped of any humanity. Maybe that’s the point? But the show doesn’t seem to have the self-awareness to pull that off.

Another Brick in the Wall comes close to a thesis during Caroline Bleau’s Act I aria as The Woman, where we see her leading a protest in front of a projection of the U.S. Treasury. The protesters look at once thuggish and juvenile. And the message is muddled. Is it anti-capitalist? Anti-government? Anti-money? Libertarian? Socialist? Anarchist? It is all of these things because it is none of them; because there is no point besides a desperate bid to tap into a zeitgeist of popular discontent without getting political so as to risk offending anyone. It is vehicle for the Pink Floyd fans of yore, who traded in their bongs for Bentleys, to feel like they haven’t lost touch. It is vindication for every smug 14-year old who ever complained that ‘real music’ died with Freddie Mercury. It is a way for the establishment, the old, the ones who’ve caused this mess we’re in, to absolve themselves of blame by crafting a faceless ‘man’ in which to pour our discontent. It is a performative, meaningless expression of rage.

And it is boring.