On the road to war as a Canadian War Artist (Afghanistan), I met General Roméo Daillaire, former force commander of the United Nations Mission for Rwanda, who famously witnessed the Rawanda genocide. At the time, I also met master warrant officer “Smitty” who served in Bosnia in the mid 1990s. While Daillaire’s struggles are well known, other peacekeepers’ are often not, and Smitty, who looks after military personnel with PTSD, suffers with the legacy of these wars himself. His job in the Balkans was to gather evidence from mass graves for war crime trials – shoes, wallets, you name it. The work was grim and haunts him still. He told me “I hate walking in forests… The snapping of twigs underfoot triggers memories of walking through Bosnian forests and realizing it wasn’t twigs snapping underfoot – they were children’s bones, very tiny children’s bones.”

Last night, at the Canadian premiere of Sophia’s Forest in a dramatic scene in which two children and their mother make their way through a war-torn forest of an unnamed locale, Smitty’s haunting stories came crashing back for me. This is the power of trauma and the power of art, that in the midst of a city at peace on a warm and beautiful May evening, sitting in a cosy theatre amongst a well-dressed audience, images of bones of dead children were triggered by this opera.

Sophia’s Forest, a one-hour chamber opera with libretto by Canadian Hannah Moscovitch and music by Estonian-American composer Lembit Beecher, was directed by Julie McIsaac and thoughtfully conducted by music director Gordon Gerrard. The orchestra consists of a very fine string quartet, percussionist and an intriguing assembly of sonic, midi-controlled sculptures (more of this later) manipulated by the composer. The opera examines the interior and exterior legacies of children in war and their experiences as refugees, specifically, the conflict of one child after witnessing the horror of her sister’s death while still having to function through the disconnect of removal to a peaceful and foreign society.

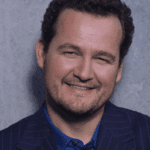

The pre- and post-war scenario is manifested throughout the opera through the guise of a young girl played impressively by Arya Yazgan, who remembers what has come before, often through gesture, drawings (projected) and silence. She is “weird,” does not speak often, and has been virtually abandoned through a complicated relationship with her war-scarred mother, Anna. Sophia is alternately portrayed succinctly as a grown woman by soprano Elena Howard-Scott. I write “succinctly” because the vocal lines of the grown Sophia’s melodies can be complex, “jagged” and challenging, but Howard-Scott delivers them with skill.

Photo Credit: Michelle Diamond

Sophia (Elena Howard-Scott) deals with trauma and her memories of the past

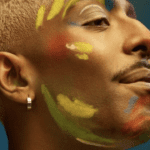

Mezzo Adanya Dunn is particularly strong in the role of Sophia’s mother, a woman who self-medicates with alcohol, drugs and sex in an attempt to cope with the horrors of seeing her child shot dead, having to abandon her body on the border and losing her husband. The guilt of the survivor, especially that of a mother who sober is cranky and drunk is neglectful, is very well expressed vocally and bodily by Dunn. For anyone who has been exposed to post-war PTSD, hers is a recognizable character.

Audrey Gao is effective and very memorable as Emma, Sophia’s lost sister, as is Luka Kawabata, who plays Wes, Anna’s Canadian boyfriend, capably. The role is thin, and I would like to have had more of Wes. The only hesitations I had with the libretto were the over-use of the vernacular f-word in Wes and Anna’s interactions, which tends to distract from the dramatic impulse of their scenes, and the tendency for adult Sophia’s role to be narrative rather than active. At times, I found it difficult to follow the story, but I think this reflects the challenges of fitting so much into only an hour’s performance time.

I spoke with Beecher about the wine-glass and bicycle-wheel sonic sculptures that are used in “dreamy sequences.” The composer described them as “electronically controlled acoustic sculptures, 16 wine glasses, each a different pitch, with 16 electronic fingers” that ring various tones, and a “digital audio station, midi-controlled, [from which he] can control the speed and the fingers.” The result is lovely, curious, and improvisatory. The music is provocative, intriguing, and borders on challenging for an ear conditioned to lyric opera. There is no ensemble work, but as my “everyman” companion Jeff said after the show, the score is “fascinating.” It is intriguing, difficult and must be a joy and challenge to conduct, perform and sing. Beecher conceptualizes the soundscape as “the world we live in” (the string quartet and percussion) and the sonic sculptures as the “the inner life,” while the voices are “journeying through this world.”

The set, soundscapes, lighting and projections are all compelling and draw the audience in well before the action of the opera begins. Director McIsaac makes some fine choices in her staging, especially when we observe Sophia and her sister Emma riding bicycles through their war-torn city, then as the mother and her two daughters escape their burning city through the forest (perhaps the most cohesive scene musically and dramatically). The conundrum brought through this scene in the forest, however, is that it illustrates both the strength of this one-hour opera yet also points to the near-impossibility of portraying such a profound subject – the price of war and exile, especially on children – over such a tight timeline.

Theirs are the stories that are literally begging still to be heard, and I hope they will.

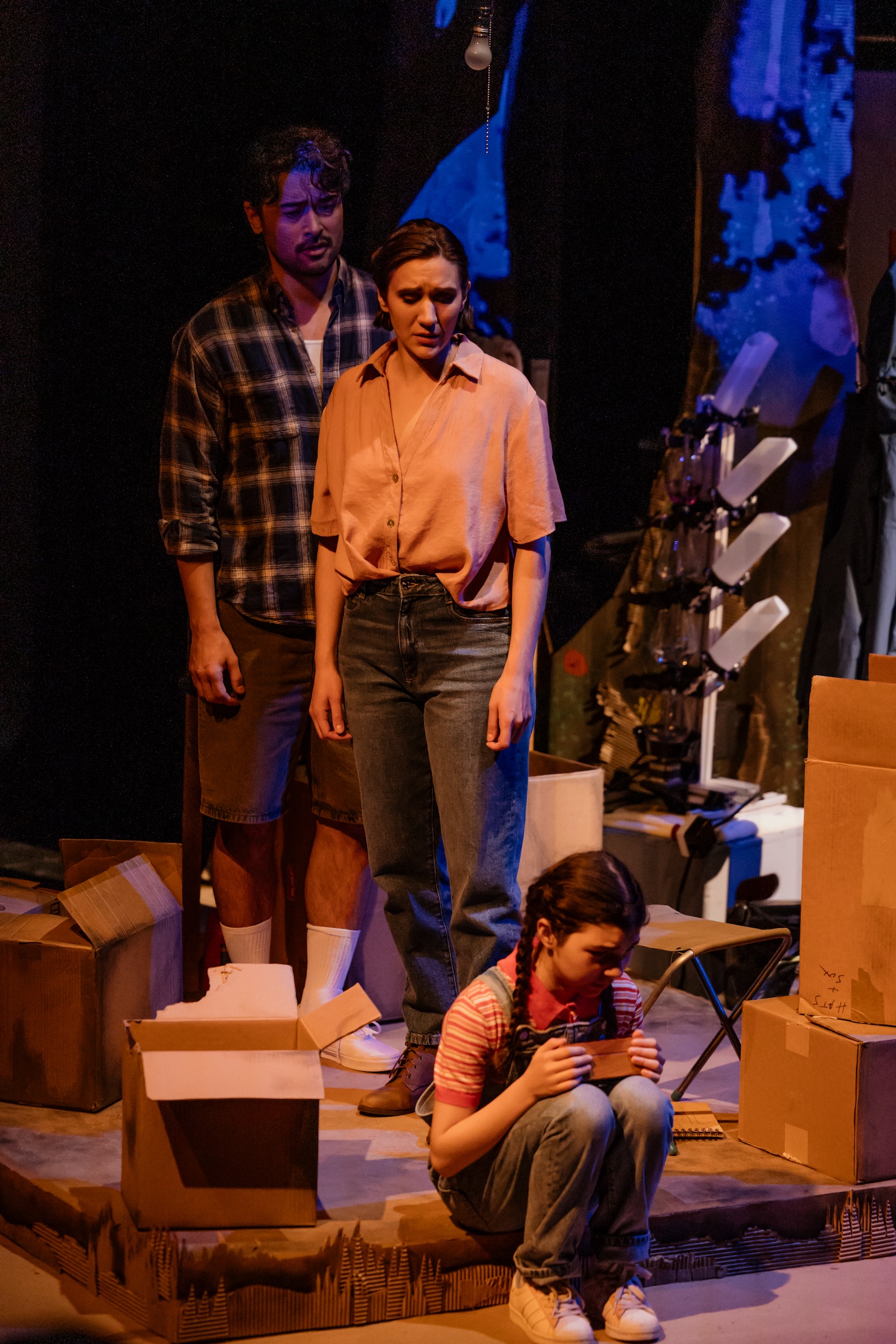

Photo Credit: Michelle Diamond

Wes and Anna (Luka Kawabata and Adanya Dunn) watch over the struggling Sophia (Arya Yazgan) in Sophia’s Forest

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.