There has been little if no question over the years that Mozart’s opera seria, Idomeneo (1781), is considered to be the composer’s masterpiece in the genre. But something new seemed to pop out at Toronto’s Ed Mirvish Theatre on April 6 that I had initially missed when I first saw Opera Atelier’s (OA) production of the opera eleven years ago.

After viewing this highly successful remount, I found that Mozart’s last, pre-Viennese masterpiece would be better understood, not via our conventional perception of 18th-century opera seria, but through the lens of the composer’s self-described genre of grosser oper (best translated as either ‘great’ or ‘grand opera’).

Idomeneo has traditionally left me a little cold over the years. I could not help asking why OA’s production worked as well as it did.

The answer to this may be found in how co-artistic directors Marshall Pynkoski and Jeanette Lajeunesse Zingg approached the term grosser oper and how well they researched Mozart’s score and his letters. The result was an Idomeneo which finally made sense.

Effectively, Mozart fused French tragédie lyrique with Italian opera seria creating a kind of hybrid performance genre. We know from Mozart’s letters that the stars of his new fusion opera were to be, by every design and intention, the orchestra, the choir, the painted sets, even some rare ensemble singing (for example, the splendid Act III quartet), and finally, solo dancing. This was to be an opera where all the elements of the production were to play an equal part alongside the very difficult music written for the singers. If anything, singers were supposed to interact and move with the staged action. In this last respect only, it is unclear that Mozart got exactly what he wanted here.

But certainly, OA very much achieved that vision with some superb dancing, Gerard Gauci’s gorgeous painted sets including a tsunami scrim and a warped dimensional palatial set mirroring the off-kilter story line, and remarkable choral and orchestral performances of a daring, timbrally adventurous score that equitably matched the visually turbulent sets. Who didn’t love the off-stage brass quartet depicting Neptune’s spooky deiform presence?

Idomeneo’s plot is essentially another Metastasio-inspired daughter/son sacrifice tale, a vehicle which Mozart appeared eager to use for launching the next phase of his career. He seemed intent on capitalizing on the popularity of Gluck’s great Parisian successes, especially the relatively recent Iphigénie en Aulide (1774) and the revised French version of Alceste (1776), each ensconced within a resurgent public interest in Greco-Roman art and architecture. With these elements in mind, OA created its own reconstruction of this rather historically unique opera in Mozart’s output.

There are multiple passages of chord progressions in Idomeneo that appear to have been lifted from Gluck’s two very popular Parisian operas, a typical compositional convention of the era. And after Mozart’s successful Munich premiere of Idomeneo, he sought to hew the opera even closer to Parisian custom when he revised it for a concert performance in Vienna. Did Mozart envision blending his love and intense study of dance with opera in the hopes of garnering more commissions for the ballet-loving Parisian public?

We shall never know. Mozart moved to Vienna almost immediately after the opera’s Munich premiere and it was to be the last time that so many integrated dancing/singing scenes were ably braided into Mozart’s rich orchestration and choral montages. OA’s production finally allowed me to understand the importance of these dance scenes depicting the freeing of the Trojan captives, the rites in honour of Neptune, and the compulsorily lengthy, entirely cathartic dance celebration concluding Act III, so typical of traditional French opera. If we don’t see these dances, we lose the 18th-century audience’s expectation for dramatic release after such a long and tense presentation of near-death shipwrecks and filial trauma.

Lajeunesse Zingg’s choreography was set in French style after the celebrated 18th-century ballet master M. Le Grand. Mozart took an intense interest in the ballet sequences to say the least, suggesting which artists would perform each of the dances, and writing special music for M. Le Grand himself.

In OA’s production, the proxy for Le Grand was rising star dancer Dominic Who, a prodigious talent who dazzled every moment he was on stage, particularly in the finale with his high cabriole stage right and an impressive grand manège to close.

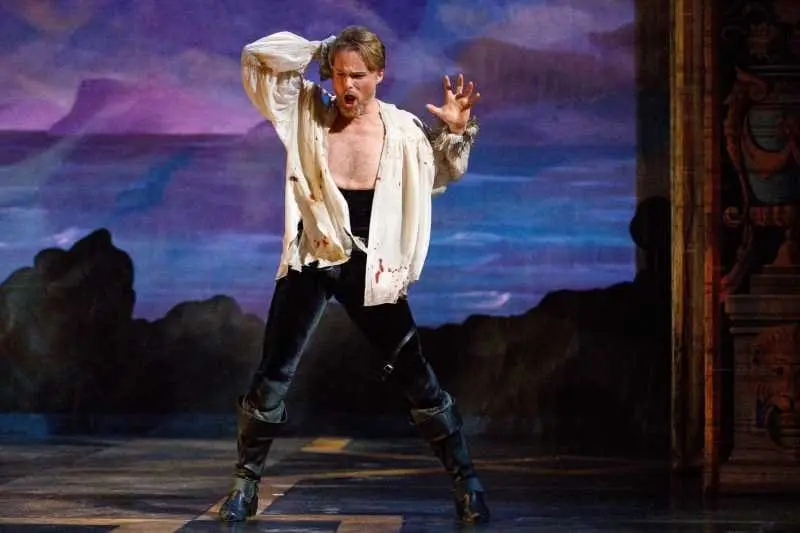

(l-r) Measha Brueggergosman (Elettra), Wallis Giunta (Idamante), Meghan Lindsay (Ilia) & Colin Ainsworth in the title role of Opera Atelier’s Idomeneo. Photo: Bruce Zinger

I also enjoyed the staging’s neo-Classical textbook acting, complete with historically accurate gestures and movement. Many I overheard near my seat and at intermission seemed troubled by ‘overacting’ or overly dramatic gestures they had observed throughout. But, I prefer to see OA successfully integrate the feel of an opera’s period dramatic qualities, emphasizing each character’s sturm und drang and thereby clarifying a piece that otherwise fundamentally lacks much plot punch.

As such, the production required team playing from all artists to integrate careful control over their arm gestures, hand positions, and general movement while they performed. It’s a new and different movement language, and not always easy to take in. The result was as far from French Baroque drama as one could imagine. For the singers, this meant far less exaggeration of gesture than one might have witnessed in the earlier era’s operas by Lully.

Above all, the neo-Classical blocking and movement emphasized tremendous symmetry of motion, line, circle, and poised gesture to stimulate the senses, so as to create a manufactured melodrama.

By contrast, the dancers were choreographed to traditional four-step phrasing, this time a true holdover from the Baroque era of Lully and Charpentier. I loved the nuanced minuet they danced at the end of Act I—not quite Baroque, but a period-styled extension into the Neoclassical era.

While OA’s reconstruction of Idomeneo might have seemed idiosyncratic and melodramatic—it was not as over-the-top as it could have been. By our contemporary aesthetic standards everything might have seemed exaggerated, but Pynkoski’s direction struck the appropriate balance.

In keeping with this, much of that world was well-embodied in Measha Brueggergosman‘s acting and focused singing as Elettra. In one of her rare appearances on the opera stage, she was, by OA’s marketing design, ostensibly the box office draw as much as she was when she sang Vitellia in OA’s La clemenza di Tito eight years ago and Elettra for OA eleven years ago, to great success.

For me, it is difficult to escape her stage presence as a recitalist of conspicuous depth. I have had the distinct pleasure of hearing her in recital several times, twice in more recent years, and remain a devoted fan of her voice. But hers is a different instrument now—softer, with a dusky lustrousness in the lower and mid ranges—not a voice one would associate with Elettra. Brueggergosman no longer tears through these pieces as she once did, and, as might be expected as her instrument evolves towards a very different technique, making use of different kinds of breath support, the famous Act III rage aria “D’Oreste, d’Ajace” sounded quite different than we conventionally might expect, more like a contained concert piece than the essential dramatic upheaval Mozart intended.

Regardless, she earned bravi from her fans, but others groused about whether a younger singer with more vocal alacrity and projecting power might have been better for this production. My take on it all is to be fair-minded to the many perspectives I overheard at intermission and afterward, and accord Brueggergosman some praise for her acting and tone, and frankly, I like her vocal projection just fine. Others will get their chance to perform this plum role too.

Mezzo-soprano Wallis Giunta as Idamante and Meghan Lindsay as Ilia offered the most interesting music making of the evening. Giunta’s voice was warm and full, and she hit her stride in Act III in her deeply affecting “Padre, adorato,” ably depicting the story’s most compelling plot point about a son trying to understand his father’s (Idomeneo) remote behaviour only to discover it is the result of having to sacrifice his own son to propitiate the god Neptune.

As a perfect complement, Lindsay delivered a roller coaster of lustrous phrasing and expression throughout her emotionally torn performance, especially in her Act II emotional nadir “Se il padre perdei”, and also in the equally affecting and nuanced cantabile masterpiece “Zeffiretti, lusinghieri” in Act III.

Colin Ainsworth‘s Idomeneo never lacked in anything his role required, presenting vigor and dynamic acting skills throughout, even if there were mild moments of struggle with some of the broader passages of ornamentation here and there. All in all, it was a tremendous outing for his first Idomeneo.

It was hard to miss the remarkable bass-baritone Douglas Williams and his striking poses, making the most of his two musical minutes in the role of Neptune, including several scenes behind the scrim flexing angry-god poses while brewing turbulent storms. And then there was striking baritone Bradley Christensen as the High Priest and Olivier Lacquerre as Arbace, both lending essential dramatic lower tessitura counterbalance to the opera’s preference for upper register roles. Christensen and Laquerre are excellent singers and actors and I look forward to seeing them in more roles with OA.

Finally, much has been made of OA striking out into new acoustic territory with this move into the Ed Mirvish (formerly Pantages) Theatre. It is true that the sight lines are better, the orchestra pit is slightly bigger and the proscenium broader in its dimensions, but there are also many unfortunate and seemingly unavoidable disadvantages to staging opera there.

The chorus, situated in the side boxes, is even further away from the pit than in the company’s traditional venue, the Elgin Theatre. It created some difficult conducting issues for David Fallis. From where I sat eight rows back, stage right, there seemed to be very few problems of synchrony but from other positions in the balcony or on the opposite side of the theatre for example, there were reports of difficulties aligning choir with orchestra.

There were also numerous acoustical delay factors to deal with. At stage centre, the sound does not project as well as one might wish. Singing volume was adequate but not always audible to its fullest potential. Singers standing stage left found their volume limited either by acoustic shadow or, in an attempt to compensate by using the side boxes as a reflective surface, accidentally created a delay which could sound eerie and more out of sync than had they projected directly into the auditorium.

These issues are not insurmountable however. It will take several runs to overcome the spatial dimensions and their acoustical limitations in what was once a hall used primarily for touring Broadway musicals with artificial amplification. As experimentation with direction continues, there will likely be compensatory measures taken to ensure that volume is uniformly distributed and audible to everyone. These minor issues shouldn’t dampen an evening of splendid music making.