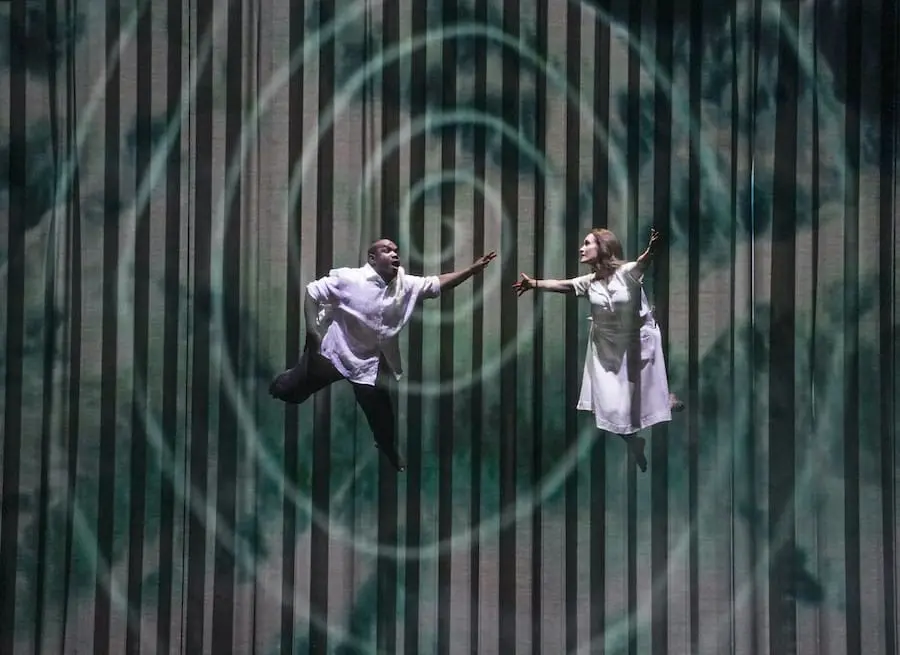

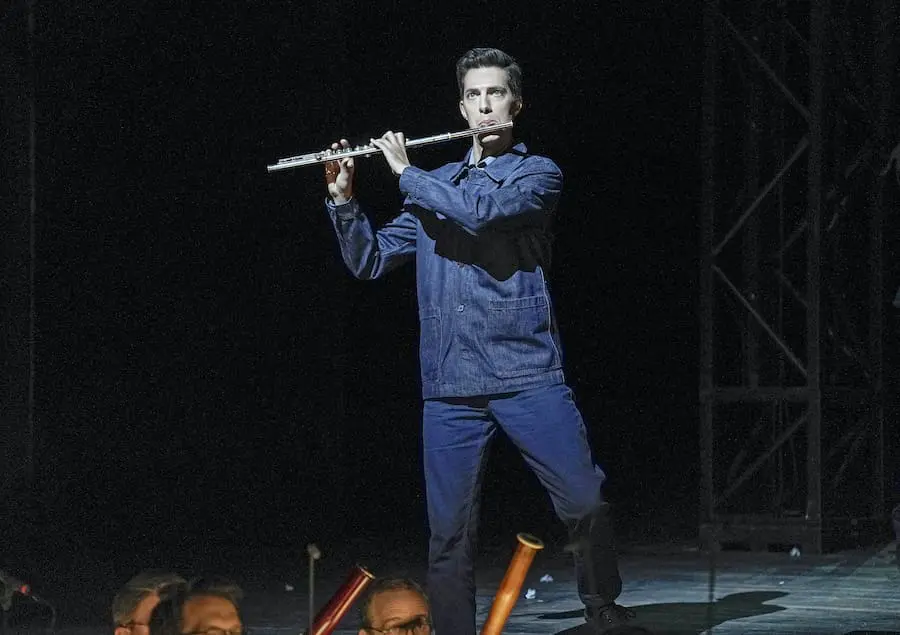

How often does an opera audience seem united by one big, heady communal high? That was the feeling at The Metropolitan Opera’s new Die Zauberflöte on May 22, a giddily joyous experience that sent me home in buoyant spirits. Simon McBurney’s tirelessly inventive, contemporized production, first seen in Amsterdam in 2012 and since then at the English National Opera and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, is at once simple and enormously complex, a combination of old-fashioned stagecraft and latter-day technological savvy. Michael Levine’s deftly mutable set isn’t much more than a cable-suspended rectangular platform on an otherwise bare stage, an elevated orchestra pit, and a passerelle. Far left on the stage apron, a blackboard-toting artist (Blake Habermann) sets up shop, sketching words and pictures that are projected (along, occasionally, with his busy hands) onto a scrim: “eine felsige Landschaft” becomes a charmingly childlike drawing of the rocky landscape in question. His counterpart to the far right is an equally busy Foley artist (Ruth Sullivan), a varied arsenal of evocative noises at her disposal. Performers enter and exit from the Met’s aisles and side doors; the orchestra’s principal flutist Seth Morris gets commandeered by Tamino for a stint onstage; and staff pianist Bryan Wagorn is likewise recruited to man Papageno’s glockenspiel. (He makes a very funny tardy entrance in act 2, coffee cup in hand, having momentarily left the resourceful birdcatcher to fend for himself.) Sarastro, dressed like a hip contemporary CEO, takes to the passerelle with microphone in hand to address his opening remarks straight to the audience, then repairs to the stage to chair a meeting of his “board” at the conference table that’s the versatile central platform’s (it rises! it falls! it tilts!) latest guise. For their climactic trial by water, Pamina and Tamino “swim” aloft, high above the stage floor.

In McBurney’s staging, surprises become the norm, and keeping the public actively entertained is as much his goal as it was Emanuel Schikaneder’s, when that jack of all theatrical trades wrote the text for, produced, staged, and created Papageno in Mozart’s opera. Had he been raised from his Viennese tomb to watch the Met’s new Flute—and once he’d gotten over the shock of two centuries of technological advancement—he surely would have recognized in McBurney a closely kindred spirit.

The opera was performed in German, dialogue (lots of it) and all, but I’ve never encountered a Flute audience more attuned to what’s being said; and for that I offer a salute to Cori Ellison, who devised the production’s back-of-the-seat Met Titles. (I find them hard to read and avoid them, but Ellison’s English earned high marks from their users.) I first viewed this production on video from Amsterdam, and I was worried whether its generous theatrical virtues would register in an auditorium well over twice the size of Dutch National Opera’s. I can’t speak for the Met’s upper reaches, but from my vantage point they came through just fine.

Musically, this Flute was top-flight. Nathalie Stutzmann and the orchestra seemed to relish their rare visibility, with a wonderful sense of give-and-take camaraderie between stage and elevated pit.

There wasn’t a truly weak link among the singers, from the piping trio of boys (Deven Agge, Julian Knopf, Luka Zylik) and the exceptionally appealing Three Ladies (Alexandria Shiner, Olivia Vote, Tamara Mumford), to Brenton Ryan’s nimble Monostatos and Ashley Emerson’s perky Papagena, to the firm and resonant Speaker of Harold Wilson and the physically imposing Sarastro of Stephen Milling—the right timbre for the role, even if its bottom-most notes eluded his easy grasp. The Queen of the Night’s extended range presented no such problems for Kathryn Lewek: she’s always been an excellent Queen, but in McBurney’s deglamorized vision, whether hobbling on a cane or furiously propelling a wheelchair, she was truly a woman possessed, singing with stellar accuracy and abandon. Lawrence Brownlee, with more voice than most Taminos, sang beautifully; so, with a lighter soprano than the classic German Paminas (Elisabeth Grümmer, Gundula Janowitz), did Erin Morley—her “Ach, ich fühl’s” was exquisitely poised and phrased. But the beating human heart of McBurney’s show, as it’s been since its Amsterdam premiere, is Thomas Oliemans’s easy, rumpled prole Everyman of a Papageno; nailing all his gags but never obtrusively milking them, he was a constant source of delight—and surely that visiting shade from Vienna would have given him, like his director, the Schikaneder seal of approval.

Related Content ⬇

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.

METROPOLITAN OPERA

MAY 19 TO JUNE 10

MOZART DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE

PRODUCTION AND CHOREOGRAPHY

Simon McBurney

SET DESIGNER

Michael Levine

COSTUME DESIGNER

Nicky Gillibrand

LIGHTING DESIGNER

Jean Kalman

PROJECTION DESIGNER

Finn Ross

SOUND DESIGNER

Gareth Fry

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

Rachael Hewer

Conductor Nathalie Stutzman

Pamina Erin Morley

Queen of the Night Kathryn Lewek

Tamino Lawrence Brownlee

Monostatos Brenton Ryan

Papageno Thomas Oliemans

Speaker Harold Wilson

Sarastro Stephen Milling

Met Opera Orchestra

Met Opera Chorus