Canadian tenor Michael Schade has been waiting patiently for the latest formal nod to his life’s work—and this one comes with a personal connection. “The Rubies mean a lot to me, because I knew Ruby,” says Schade, who next month will be named an Honouree of the Opera Canada Awards, lovingly nicknamed “The Rubies”, after Ruby Mercer, the Canadian operatic force of nature who founded both Opera Canada magazine and the Canadian Children’s Opera Company.

“Ruby was one of those larger-than-life characters,” Schade says, recalling her unique, old-world flair and strong connection to Canada’s operatic network. “You had the feeling that you were in the presence of royalty.”

Schade has been on the short list several times for a Rubies honourific, and it’s clear that the tenor is tickled to finally celebrate with fellow Canadians. “It’s right up there with that other honour I got, which is to be an Officer of the Order of Canada,” he says, with an audible smile in his voice. “I tell you, without a joke, that I think the Ruby is just as important.”

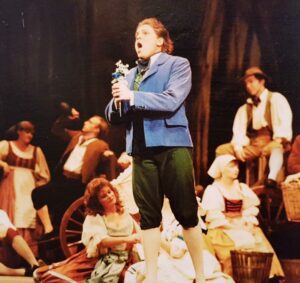

Born in Geneva and raised jointly in Germany and Canada, Schade’s career has been as international as his daily life. His training took him from St. Michael’s Choir School in Toronto, to the University of Western Ontario, and finally to Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. His professional operatic debut came in 1988 on Canadian soil, as Jacquino in Fidelio at Pacific Opera Victoria. Over three decades later, Schade’s operatic career is anchored in his long-standing collaborations at Canadian Opera Company, Salzburg Festival, and Vienna State Opera; signature roles like Tamino (The Magic Flute), and Tito (La clemenza di Tito), and his GRAMMY and JUNO-winning discography of recital, concert work, and oratorio.

Now in his thirty-third season, Schade is lauded on both sides of the Atlantic. In fact, Schade’s 2017 appointment as Officer of the Order of Canada was an echo of his being named Kammersänger (“chamber singer”) by the Republic of Austria in 2007, a title reserved for distinguished singers that he received alongside fellow Canadian Adrianne Pieczonka. “I’ve been very lucky, and I’ve had a whole bunch of really lucky breaks. Yes, and I did work very hard with that luck.”

Schade takes clear pride in his work, and attributes much of his success to consistently diversifying his singing. As a student, Schade received advice on what were considered the only two career paths for a young Canadian tenor: sing for the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and hope for a break on the Met stage, or get into the coveted Ensemble Studio program at the Canadian Opera Company. “Nobody ever thought about working hard on recitals, nobody thought about how important oratorios were,” he says. “They are three related cousins, essentially—opera, oratorio, and recitals.

“People have these crazy preconceived ideas to this day, and it’s wrong. It’s completely wrong,” Schade says, with all the hindsight of his career guiding his simple advice. “What you need to do is really learn vast amounts of repertoire, and learn how to sing. It’s more than just opera singing.”

For Schade, diversification goes hand-in-hand with constantly exploring new repertoire, an exciting, ongoing experiment in vocal development. After retiring his Tamino after 285 performances of the role, he has debuted heftier roles like Britten’s Peter Grimes, and Florestan in Fidelio. “I’m trying to keep the options open for repertoire, but I never push it beyond what is healthy,” says Schade. “I’ve had a 33-year career already, and I feel terrific.”

Schade’s options also evidently include the mentorship of opera’s young artists, an area of his career that continues to grow. The tenor initiated Salzburg Festival’s Young Singers Project in 2008, and was its Creative Director until 2010; he is also Artistic Director of the Hapag Lloyd Stella Maris International Vocal Competition, famed for its unique venue aboard a cruise ship. Most recently, Schade has begun a professorship of vocal historical performance practice at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna (MDW). “I love young singers, because generally speaking, they are full of life,” he says. “They are often as volatile and as insecure as I was when I was their age.”

And, in step with the impressive reputation that Canadian opera singers have abroad, Schade has observed Canada’s young talent with great enthusiasm. “It’s amazing to see what the actual progression is,” he says, noting the likes of Canadians Rihab Chaieb, Wallis Giunta, and Joel Allison as artists to watch. “It reminds us that voices are a little bit like fine wine. If you have really great grapes and really great earth, you get to make really great wine. And Canada has really good, good earth to make really great singing wine.”

For Schade, becoming a Rubies Honouree has unique value in its connection to young Canadian artists, and to his homegrown audiences. “It’s not an unattainable thing for people who are starting now. It is a milestone that you can look to,” he says, hoping to be an example of success for those coming up behind him. “It feels like a great honour because for me, Ruby was such a milestone and such a shining light.”

Schade spoke with Opera Canada from his home base in Vienna, a vantage point enough removed to observe the Canadian opera scene with some objectivity. “I would describe it as vibrant, supportive, proud, wonderful,” says Schade. “The last years of the Canadian Opera Company have been such that the COC was a shining light of not only Canadian pride, but the world was noticing what was happening in Toronto.”

Currently, the performing arts certainly look quite different in Canada than they do in Austria, yet Schade looks on with optimism. “I try to wake up happy and I try not to get down, and I try to stay positive, whatever I do. And I’m not going to jump on this bandwagon that it’s all decimated, all is destroyed, it’s all terrible, and it’s all been rendered useless. I do think there’s a potential seismic shift that could happen.”

Yet if there’s advice he can offer from his platform, newly enriched as a 2020 Rubies Honouree, Schade insists that opera’s post-pandemic recovery will come not only out of patience or money, but out of devotion to the art. “It would be a mistake to think that somebody’s going to turn on the tap and it’s all going to come back to normal. That will not happen. We have to work really hard to keep it viable, and we have to work really hard at showing the joy of it. That doesn’t work with money managers, that works with artistic directors who have a vision.”