After stints in Berlin and Madrid, Claus Guth’s 2008 production of Don Giovanni finally arrived on the Opéra Bastille stage this week for the opening of the 2023 season. The question is: is it fifteen years too late? Can revivals be effective more than a decade after their creation? I liked the production when I first saw it at the Salzburg Festival in 2011 with Yannick Nézet-Séguin—then, just a rising star—conducting the Wiener Philharmoniker. It was impressive how thoroughly he mastered the score from the first crashing chords to the finest nuances, his sensitivity to the singers, and acute awareness of what was going on the stage.

Perhaps it’s due to this indelible Salzburg memory, which set the bar very high that the Paris reprise was disappointing. And Antonello Malacorda, who is an excellent conductor, got off to a bad start with an underwhelming overture and languid tempi in the first act, hence the lack of synchronization with the singers.

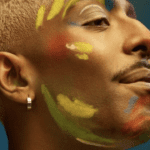

The cast of Opéra national de Paris’s production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni Ⓒ Bernd Uhlig, Opéra National de Paris

In its day, Guth’s production was visionary: economy of means in the stage designs and masterful precision in the dramatic direction. A single location features a forest or, rather, a patchy fir grove and rocks on the outskirts of some urban sprawl. Designed by Christian Schmidt, it slowly rotates like a dark merry-go-round where the characters search for each other, cross paths, or hide. There’s a bus shelter on its edge, where Donna Elvira (Gaëlle Arquez) sits gripping a small suitcase while singing her despair. Joined by Leporello (Alex Esposito), the two, stranded in the middle of nowhere, resemble Didi and Gogo in Waiting for Godot. Don Giovanni (Peter Mattei) is on the prowl, shot and injured by the Commendatore (John Relyea) in the first scene; he’s not the notorious seducer but a wounded animal desperately hunting his prey. Leporello supports him to the bitter end. Instead of master and valet, they are equals and fellow addict-derelicts, sharing a passion for women and heroin.

For in Guth’s concept, all characters are equal in the face of life and love’s tragic illusions. Social standing has no importance. In scene 1, Donna Anna (Adela Zaharia) is not a rape victim but a woman in hot pursuit of Don Giovanni; together, they play a game of erotic hide and seek through the woods at night. But after furtive lovemaking, she remains smitten for life while he ticks off a fresh conquest on his list and continues his desperately addictive search. The question is, who is worse off?

Don Ottavio (Ben Bliss) is equally disillusioned as he helplessly observes the downward spiral of his fiancé. Finally, Donna Anna steals his pistol, runs into the woods, and shoots herself.

The pair Masetto (Guilhem Worms) and Zerlina (Ying Fang) usually offer some comic relief and down-to-earthiness. However, here again, Zerlina appears irretrievably smitten after her encounter with Don Giovanni, and it feels like Masetto has enough pent-up anger to incite a revolution.

Don Giovanni (Peter Mattei) and John Relyea (Il Commendatore) in Opéra national de Paris’s production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni Ⓒ Bernd Uhlig, Opéra National de Paris

Worms is very promising in this role, even if, on opening night, he got little support from Malacorda and was out of sync with the orchestra in his first aria. Notwithstanding, he and Ying Fang deliver the freshest and most energetic performances of the evening, which otherwise tended toward a feeling of “been there, done that,” especially on the part of Peter Mattei, who has sung the role for over twenty years. He lags slightly behind in the first act, seems listless in the duo with Zerlina, perhaps in keeping with his character’s injury. But “Finch’han dal vino” is spectacular and his beautiful timbre and phrasing in the much-awaited serenade is unequaled.

For that matter, all singers delivered top-level performances: mezzo-soprano Gaëlle Arquez takes on the testy role of Donna Elvira with ease, and though the intonation was unstable in her opening scenes, she gains precision in the following. Adela Zaharia has impeccable style, sensual vocal colors, and nuances. Gripping in “Or sai chi l’onore,” delicate and nuanced in “Non mi dir,” she holds the audience’s attention even when the overall dramatic energy wanes. Ying Fang has a lovely voice with sparkling high notes.

Making his debut at the Paris Opera, the American Tenor Ben Bliss sings with endless breath, supple vocal line, and beautiful vocal colors; his two arias are show-stoppers of pure poetry. Alex Esposito‘s “no future” Leporello becomes the driving force behind the production as he castigates Don Giovanni in Notte e giorno fatigar, teases Donna Elvira in the Catalogue Aria, prods Masetto, “Non balli, poveretto?” providing the vital vocal and dramatic energy to sporadically enliven the evening. Likewise, John Relyea‘s final entrance as the Commendatore is electrifying, his massive stature, charismatic presence, and sonorous voice, looming through the penumbra to deliver the final and fatal blow.

Why, then, with so much talent on stage, does it all fall flat? One can’t only fault the conductor, who indeed has good moments especially in the Finale. The problem is that the very dark side of this production, which shocked audiences in 2008 and was its force and its difference, now rejoins the same routine grimness that we’ve all grown accustomed to. And— the drama is gone. It seems that the ambitious productions of great directors like Claus Guth and Krzysztof Warlikowski (Iphigénie en Tauride 2006), are the most difficult to revive. In contrast, the classic repertoire house productions like those of Zeffirelli at The Met or Boleslaw Barlog at the Wiener Staatsoper, where it’s more a question of décor and costumes, are easier to re-staged.

With Guth’s Don Giovanni, by the Finale, the game has already played out; there is no graveyard, no final banquet, no musicians on stage. A tree stump serves as a table for preparing more drugs, and cans of beer replace the “eccellente Marzimino.” The epilogue having been omitted, the performance ends after Don Giovanni’s unspectacular death—so there’s no catharsis, just time to go home after yet another of those “no future” productions.

Related Content ⬇

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.