Experiencing two concert presentations of Wagner’s Die Walküre within a week on two different continents presents a unique set of challenges. Along with the exhaustion of travel, how does one adjust to the diverse artistries of soloists, orchestras, and conductors? How does one scale the mountain of the epic while curling up in the valley of the intimate? Is it even possible to listen to Wagner with fresh ears in this, the age of Youtube and Spotify and iTunes?

These questions were vividly present as Vladimir Jurowski and the London Philharmonic Orchestra performed a concert-meets-theatre version of Die Walküre, one so singular it inspired a rethink of not only the work but of Wagner, 19th-century music, 20th-century music, religion, spirituality, art, love, violence, and theatre. Amidst all these big ideas (ones the maestro is unquestionably adept at presenting), the work’s musical intimacy was magnified to such a degree that breath-holding, chest-raising, eye-saucer-ing, nails-dug-in-hands moments were not the exception at the Jan. 27th performance but rather, the spine-tingling norm.

The LPO’s second concert presentation within the Ring Cycle (they performed Das Rheingold last season), Jurowski (who is Principal Conductor and LPO Artistic Advisor) led a precise, passionate, lushly sensualist performance, making the orchestra a full, ripe partner to the composer’s varied and recognizably human cast of characters. Pierre Martin’s video designs (featuring elements from the natural world) and Malcolm Rippeth’s moody lighting integrated music and drama in one seamlessly elegant package.

Freed from pit constraints, the LPO exuded theatricality while whispering intimacy; rather than falling into the bombast trap, its horn section offered curvaceous, wholly rounded tones that suggested quiet allegiances, sensual assignations, and shifting emotional states. Such an approach inspired a rethink of the link between immense and elemental within the greater dynamic whole, certainly a revelation for the opera, and indeed, the entire Cycle. Bass Stephen Milling, as Hunding, was a glowering, macho presence beside mezzo-soprano Ruxandra Donose’s soft, feminine Sieglinde; her chemistry with tenor Stuart Skelton, as a touchingly tormented Siegmund, was pure poetry. Jurowski favoured lush harmonic textures that underlined eroticism and soulfulness in their scenes, making the contrast with Act II all the more stark.

Indeed, the painful paradox between the spiritual nourishment of such connection and the terrestrial bounds of its realization was given a dramatic reading in fierce, scalding tones throughout most of the harrowing second act. Sculpted gestures toward what followed Wagner (namely Zemlinsky, Schreker, and the Second Viennese School) were integrated within sonically unrelenting portraits of Wotan (bass-baritone Markus Marquardt), Fricka (mezzo-soprano Claudia Mahnke), and Brünnhilde (soprano Svetlana Sozdateleva). Taut sectional colouration breathed of painful fissures between lovers, parents, partners, generations, men, and women.

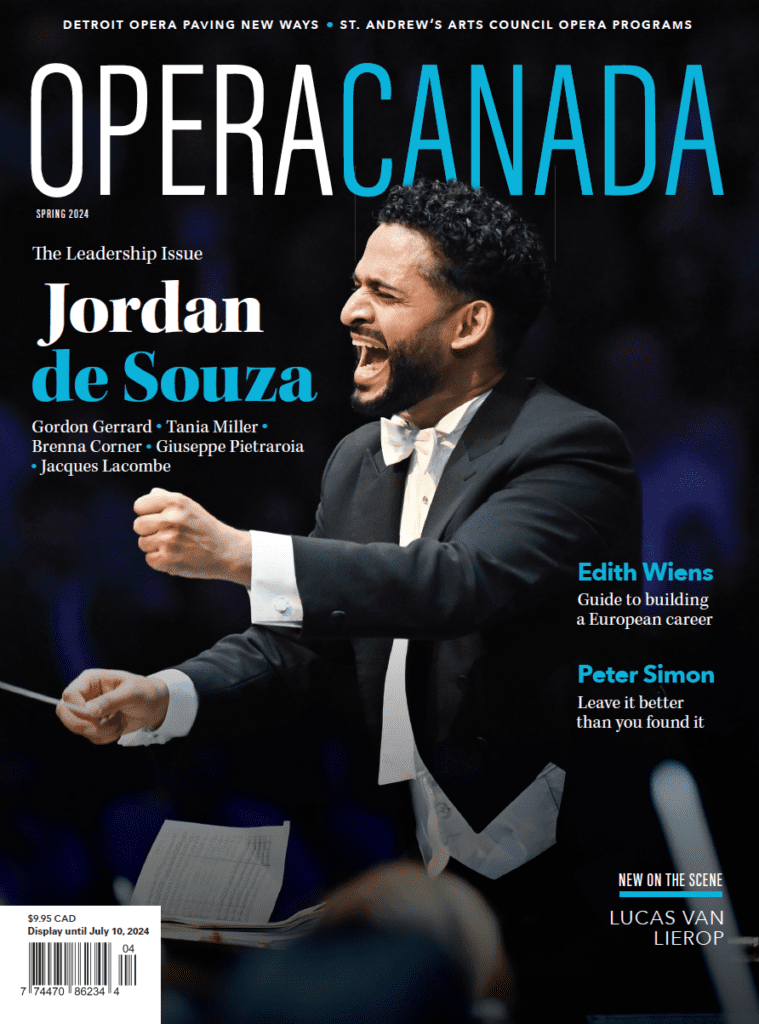

Markus Marquardt (Wotan) and Svetlana Sozdateleva (Brünnhilde) in London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Die Walküre. Photo: Simon Jay Price

In Jurowski’s hands, Wagner’s epic drama sounded less a narrative on the fall of the gods than a portrait of a family coming apart. In the program notes he commented that he thinks of Act II as “an Ibsen play put inside a Homer epic” and indeed, the performance was Ibsen writ large, in wrenching tones of blue, black, and shattered gold.

The famous “Ride of the Valkyries” which opens Act III was less boom-bang intimidation than a sonorous fluttering strings and lilting woodwinds, providing requisite lightness and delicious textural contrast.

This focus on divergent sonic structures between and within acts and scenes realized its ultimate expression within the opera’s the closing scene. With Sozdateleva simply sitting on a chair (one of two placed symbolically on either side of the podium) one could feel Brünnhilde entering her deep sleep encircled by fire, as the sensuous rippling of the strings, briskly paced, whispered licks of hot flame in curly-cue lines. Thus was the delicious anticipation of Siegfried born in this magically quiet moment, less of a curt conclusion than a sighing ellipsis.

In all fairness, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Andrew Davis, had an entirely different task in presenting solely the first act of Die Walküre (Jan. 31st, seen Feb. 2nd). A blazing reading of “Ride of the Valkyries”, along with a performance Alban Berg’s “Three Pieces For Orchestra”, made up the program’s the first half, with a chorus of “Happy Birthday” inserted into the former (with members of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir filling the choir loft), catching the delighted maestro entirely by surprise, and turning the auditorium of Roy Thomson Hall into a giant, jovial singalong.

Unlike the LPO, the Toronto orchestra was arranged with smaller strings firmly on one side and in front of the maestro, cellos/basses on the other. This gave less of a sweeping feel to Wagner’s epic score, though such placement nicely highlighted the bronzed warmth of the low strings, and allowed the work of Principal Cellist Joseph Johnson to shine. His songlike reading of the solo moments, supported by a watchful Davis and very careful orchestra modulation, allowed for an equal partnership with the talented trio of vocal soloists, making for a lovely sonic unity.

Nevertheless, Davis (who is TSO Conductor Laureate and Interim Artistic Director) took a workmanlike and engagingly even-handed approach, emphasizing geometric horns and buzzsaw strings, each section jostling in a fashion that nicely reflected the power battles inherent to the work. This was very much a concert performance, with no theatrical elements within the presentation, and artists performing basic perfunctory gestures, but it was no matter, for within the glowing tones lay a square focus on momentum. Right from the first thrumming notes, which brimmed with buzzing basslines, Davis engineered a keen, relentless drive that highlighted the work’s cinematic scope. The pace didn’t allow the TSO much in the way of leaning into phrases or exploring varied textures, but the upshot was an orchestrally attentive approach where the spotlight largely stayed on soloists Lise Davidsen (soprano), Brindley Sherratt (bass), and Simon O’Neill (tenor), all making their TSO debuts.

Sherratt’s Hunding was less outwardly murderous than inwardly brewing, an avuncular if charismatic figure of quiet intensity; such an approach was a delightful contrast to soprano Lise Davidsen’s bright Sieglinde. A statuesque presence, the 2015 Operalia winner navigated the score’s soaring lines with thrilling aplomb, her pure, gleaming tones and smooth flexibility hair-raising in intensity at points. Likewise Simon O’Neill’s lyrical reading of Siegmund brimmed with a fiery warmth to match the orchestra’s. His “Walse!” was a richly textured cry for cosmic unity (an interesting contrast to Skelton’s approach in London, which came across as an anguished shriek into the void). O’Neill’s scenes with Davidsen were shot through with lyrical tenderness and yearning.

Two wildly different approaches to one ferocious score across two continents makes for an exhausting, exhilarating, and very enlightening experience. One comes no closer to plucking out the heart of Wagner’s mysterious world of gods and humans, but is left feeling awed, grateful, and keenly aware of the deep, dark recesses of human nature, and the fraught nature of living, loving, and listening.