I can’t believe that it’s 2021, one week after the U.S. swore in its first woman and first person of colour Vice-President, and yet here I am reviewing an opera where a white director sees no problem with putting an all-white cast of singers in brownface makeup and hijabs to portray fictional characters.

On Jan. 21, Montreal contemporary opera producer Chants Libres premiered a filmed sneak peek of L’orangeraie, a new opera by Lebanese composer Zad Moultaka, with a libretto that Québécois writer Larry Tremblay adapted from his own award-winning, internationally best-selling 2013 novel of the same title (The Orange Grove in its English Translation). If the excerpts shown represent the opera’s choicest bits, it doesn’t augur well for the complete work’s premiere, which has been postponed to September 2021 due to COVID-19.

Tremblay’s story is about twin brothers from an unnamed sunbaked, fragrant desert country. After a bomb form “over the mountain” kills their grandparents at their orange farm, the brothers’ father swears revenge. He decides to sacrifice one of his young sons to the war, against their mother’s wishes. Although Tremblay has picked a vaguely Levantine setting, mentions suicide bombers, and uses Muslim-sounding names for his characters—Aziz, Amad, Soulayed—he carefully avoids any mention of specific geography or religion. The book has been described as a fable about the innocence of childhood and how adult hate and prejudices corrupt that idyll. Tremblay’s poetic language paints pictures of the environment through sensual, richly evocative descriptions, rather than fleshing out the psychology or motivations of his characters.

By leaving so much to the reader’s imagination, Tremblay’s book largely avoided criticism of stereotyping or cultural appropriation. The same can’t be said for the opera version’s staging due to the director’s unfortunate choice of a literal, geopolitically realistic interpretation of the test.

The staging is by Chants Libres’ founder and artistic director Pauline Vaillancourt. Vaillancourt has a reputation for her avant-garde ideas, but here she demonstrates a singular lack of imagination. She darkens the white singers’ complexions with greasy brownface makeup (and badly executed brownface at that). She dresses the mother—fair-haired, blue-eyed soprano Stéphanie Lessard—in a hijab, only to have her rip it off in front of everyone in a moment of emotional anguish.

The audience is confronted by the most basic, vulgar form of privilege: Dress a white person up in the skin tone and clothes of a person of colour; plunder the religious symbols of a group that faces prejudice and suspicion and use them as props; and take an allegorical plot and assign it an ethnic identity, essentializing people from that ethnic group and reducing them to the most insulting, demonizing and dangerous of stereotypes. Because let’s not forget that L’orangeraie is being staged in a city where actual Muslim women face discrimination and even violence for the hijab, and in fact are barred from wearing it in certain professions.

These singers can wipe off their foundation and change their clothes at the end of the night, and return to the comfort and security that their natural-born skin affords them. But by dressing the mother in a particularly recognizable style of hijab and artificially bronzing the skin of her performers, Vaillancourt comes frighteningly close to insinuating that those specific people—rather than the undefined people in the book—are terrorists, brutal and barbaric, willing to kill their own children. And this just three years after a young white man entered a Québec City mosque and murdered six Muslims at prayer.

If L’orangeraie is meant to be a fable and a metaphor, Vaillancourt could have selected any other setting, fantasy or not. Making the father and militants into white supremacists would have been a brave choice, not to mention a timely one. Alternatively, if Vaillancourt wanted to keep the work grounded in some kind of Middle Eastern aesthetic and societal construct, she could have taken the trouble to cast brown singers. By doing neither, she has succumbed to that cheapest and laziest of artistic devices, Orientalism.

L’orangeraie contains more practical disappointments too. Moultaka’s vocal score comes across as somewhat monotonous. There’s little variety to his formula: one syllable per note with repetitive loops of minor thirds or diminished fifths with no attempt at anything approaching harmony or lyrical shape. The instrumental writing is better, with sinuous phrases for the woodwinds and interesting layers of percussion. In comparison, the singers are so limited they’re almost superfluous, and you’re left with the impression that the whole things would have worked better as a play with incidental music (Tremblay has already adapted L’orangeraie for the theatres in 2016).

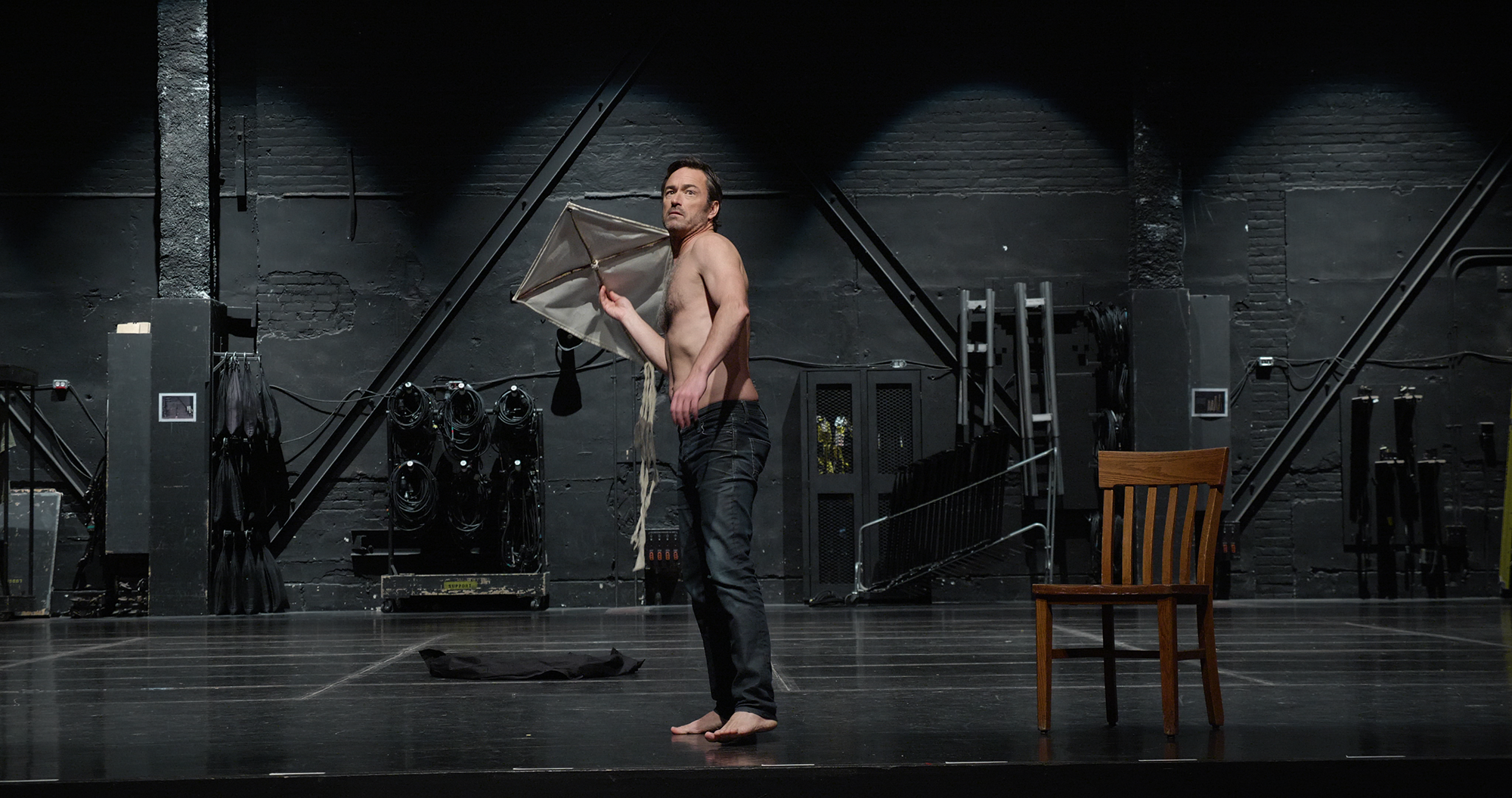

There are also significant problems with the production that have nothing to do with the appropriative elements. Light, warmth and colour play huge roles in Tremblay’s text, but they’re completely absent from Vaillancourt’s staging. The lighting is cold and dingy, to the point where it’s difficult to see the singers’ faces. There are no backdrops or projections—Vaillancourt places her performers either in various locations in the hall, or on the bare stage with the orchestra, with all the backstage cables and crates exposed, student workshop style. It’s not clear if other visual elements are still being developed or if this is, indeed, the final look.

The book features a narrator-teacher figure who frames the story. Vaillancourt keeps this character (actor Sébastien Ricard) but inexplicably makes him a silent, pantomimed cipher, shirtless and barefoot. At times, a recording of his voice speaking lines plays at the same time as the singers are intoning something, making it hard to understand both. Anyone who hasn’t read the book will only be confused by this element which, in the absence of any helpful narrative or musical function, serves no clear purpose.

The singers do their best with the material Moultaka gives them. There are notable performance by Vancouver countertenor Nicholas Burns as the brother Amad, baritone Geoffroy Salvas as the recruiter Soulayed, and tenor Jacques Arsenault as the father Zahed. I’d be interested in knowing if any of them balked at the brownface, or raised objections—not that they should ever have been put in that awkward position in the first place. The Nouvel Ensemble Moderne play with their usual intellectual and technical virtuosity, efficiently conducted by Lorraine Vaillancourt.

It says a lot about the amount of gaslighting people of colour have to endure that I initially questioned whether brownface was actually used, and went to great pains to scrutinize production stills and artist headshots, instead of simply trusting my own eyes. I’m also fully expecting this review to be vigorously contested by people who don’t believe racism and discrimination are problems in the opera industry. I’ll be told that I “misunderstood” the director’s intent, or that no disrespect was intended so that makes it ok. A North African friend warned me to be prepared for backlash.

I won’t go so far as to call L’orangeraie overtly racist, but it is shockingly insensitive and regressive. At a time when we are celebrating how far we have come, it’s also a reminder of how far we have to go.

You can read Chants Libres’ response to this review here.

Prelude to the opera L’orangeraie was available to view online by purchased link January 21-24, 2021.