Alessandro Scarlatti’s Il primo omicidio (1707), recounts the first murder in the history of mankind. Cain and Abel are the sons of Adam and Eve. Cain, a farmer, becomes enraged when the Lord accepts the offering of his brother Abel, a shepherd, in preference to his own. He murders Abel, whereupon the Lord punishes him to a life of wandering. With time, Cain settles, building a city and fathers a line of descendants. Indeed, this rare oratorio (seen Feb. 6th at Opéra national de Paris) proved fertile ground for a meeting of minds between the iconoclastic Italian director Romeo Castellucci and that cult-figure of Baroque music, purist and exigent researcher and conductor René Jacobs.

Given his age and notoriety, one would tend to see Jacobs as the conservative pole of this collaboration, but on the contrary, his interpretation is revelatory. By unearthing a virtually unknown score of indescribable beauty, he exposes us to an essentially new work. He breaks his own rules by augmenting the number of players in his B’Rock orchestra in order to adapt to the dimension of Palais Garnier—a wise decision considering the problems that other groups such as Les Arts Florissants have had with the acoustics of this hall. With a few more continuo players and a bolstered wind section, the Belgian conductor manages astonishing subtleties in turn humorous and tragic, grandiose and intimate, grating and then soothingly warm.

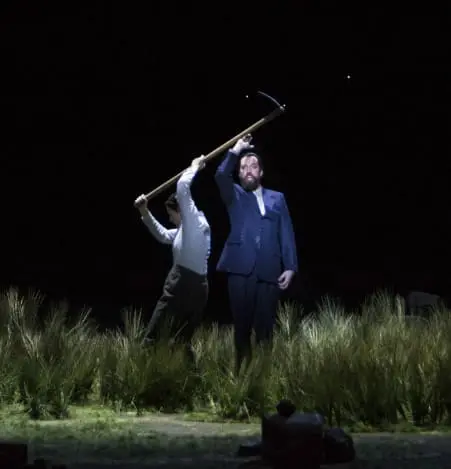

Olivia Vermeulen (Abele) & Kristina Hammarström (Caino) in Paris Opera’s Il primo omicidio. Photo: Bernd Uhlig

One of the great countertenors of his era, Jacobs is attentive to every breath and vocal inflection of the singers. One can see they are at ease, beginning with Swedish-born Kristina Hammarström whose rich timbre and excellent projection and diction are ideal for this repertoire; she is moving in the role of the child criminal Cain. Dutch mezzo-soprano Olivia Vermeulen is equally convincing as the younger brother Abel; her stylistic perfection, spinning tones and nuances are mesmerizing. As Eva, the Norwegian soprano Birgitte Christensen has some of the most stunning arias of the evening—in “Caro sposo, prole amata” she reins in her full-bodied timbre to create the finest pianissimi—the effect is riveting.

The role of the Voice of God could not be better served than by the clear ringing tone of German countertenor Benno Schachtner. Canadian bass-baritone Robert Gleadow is the only member of the cast who is not making his Paris Opera début; his first appearance here was as the Steuerman in Tristan und Isolde in 2008. His return in the relatively small part of the Voice of the Devil reveals his fabulous development in the intervening years. I heard him as Leporello at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in 2013, where, though his acting left an indelible impression, the voice was less remarkable. Here, he has audibly gained strength in the lower range, the projection is excellent throughout and the voice is thrilling. Another extraordinary performance was that of Scottish tenor Thomas Walker as Adam. It is rare to hear such precise intonation and rich timbre without faltering an instant in such a difficult and exposed part.

Romeo Castellucci has been the mastermind behind a string of operatic successes in recent years, and given that he is the sole designer of the sets, lighting and costumes, these are characterized by extreme coherence and unity. But in this staging of Scarlatti’s oratorio, many of his well-honed practices give an impression of déjà vu. His use of abstract images in the first act, and then a complete change for a realistic, physical setting in Act II—as he did effectively in his Brussels Magic Flute—do not make the same poignant impression here. This may be because with Cain and Abel, we are dealing with one of the fundamental parables of our civilization and not an illusory fairy-tale.

Nor does the unexpected apparition of a multitude of individuals in Act II—in this case, children, some of whom are doubling the six principle characters—further strengthen the narrative. As he often does, Castellucci gives the singers stylized movements, but in this production, they resemble badly executed Robert Wilson gestures from the 1980s. In the second act, where the children mime the main characters who sing from the orchestra pit, their gestures become a kind of parody of opera singers. Nevertheless, these mini-personages are fragile and deeply touching, especially Hippolyte Chapius who exemplifies the doleful remorse of Cain.

Birgitte Christensen (Eva), Thomas Walker (Adamo), Kristina Hammarström (Caino), Olivia Vermeulen (Abele), Benno Schachtner (Voce di Dio) in Paris Opera’s Il primo omicidio. Photo: Bernd Uhlig

Overall, Castellucci’s production is beautiful, in particular, the Rothko-like backdrops and visual concept in the first act, but the cutting-edge comes from Jacobs’ meticulous restoration and luminous interpretation of this 300-year-old masterpiece.