SUBSCRIBE TO DIGITAL AND/OR PRINT MAGAZINE

SPEED ROUND WITH

MARK WILLIAMS

Favourite living composer?

John Adams.

Book you’re currently reading?

John le Carré’s

A Most Wanted Man.

Favourite neighbourhood in Toronto?

College Street!

Favourite quality in a person?

Humour.

*this text was originally published in the spring 2022/23 print version of Opera Canada magazine

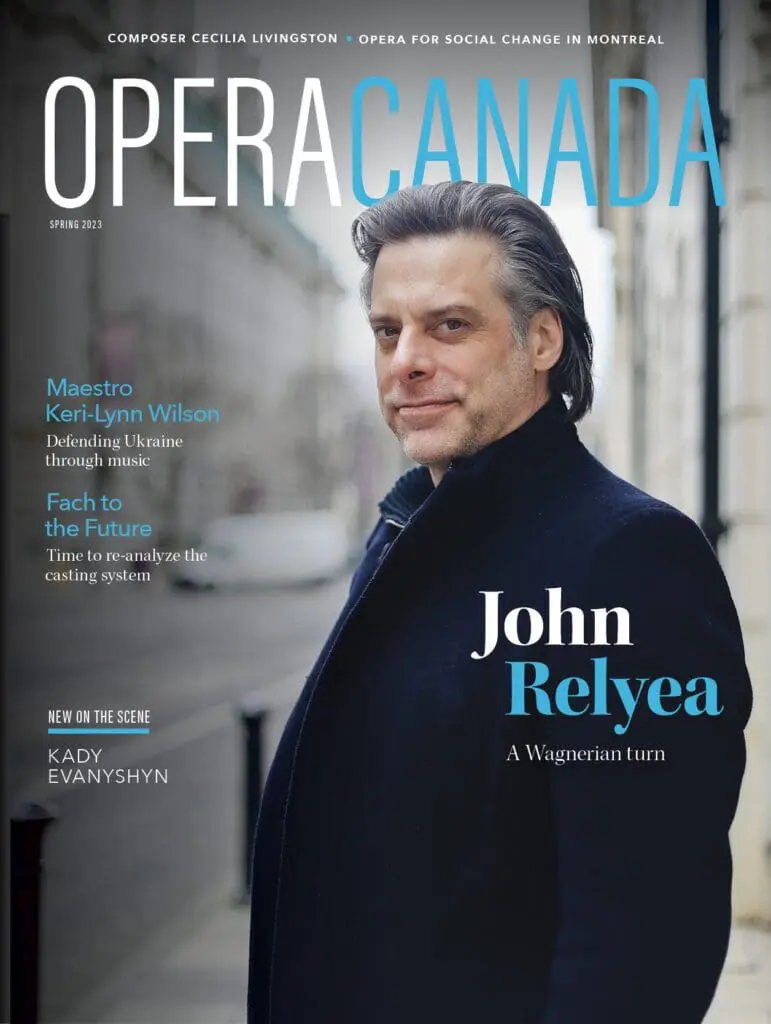

Mark Williams is the new CEO of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. He has served in leadership roles with The Cleveland Orchestra and the San Francisco Symphony.

Lucia Cesaroni: From San Francisco to Cleveland and now Toronto, how have you developed your leadership style?

Mark Williams: Trust and integrity are fundamental for me, but they require give and take. A dictatorial approach can get you so far, but without trust, you don’t have speed. Speed in business is incredibly important, and the primary driver of speed is trust.

LC: Okay. Why?

MW: If I trust you, you come to me and say: this thing you did, it’s not working. We skip the doubt or defensive “you’re trying to get my job” or “you’ve never liked me” parts. Established trust means I know that what you’re saying is for my good and the good of the company. And I can immediately get to solutions. Action. We’ve saved a lot of time and emotional energy. A facilitator recently presented trust as an equation: T = C + R + I / O (trust equals credibility plus reliability plus intimacy divided by self-orientation, or ego). So if you are credible, you’re reliable, you can develop intimacy with people, but divide that by a very high ego and that makes trust or vulnerability more difficult. The lower the ego, the faster we can arrive at trust.

I started in this business when I was 22 years old. I was young, black and I’ve always looked younger than I am. I felt people assumed that I didn’t know what I was doing. So it’s also about credibility for me. I wanted to walk into a room and I wanted you to know that I know what I’m doing. Now I’m at a different stage in my career. People don’t question my credibility. So what happens if I continue to lead in that way? What happens to your team when they constantly feel they’re being tested? Instead, I want to know: What motivates you? What are your values? And this establishes intimacy and trust. Intimacy in a professional context, of course!

Mark Williams reported a surplus of $901,000 for the TSO’s 2022 fiscal year, resulting in an overall accumulated surplus of $781,000 in September 2022 Ⓒ Max Power

LC: Of course! Well, confidence follows competence.

MW: Leadership also takes vulnerability. You become a leader because you’re good at doing things. But as you get to the top, you are responsible for fewer day to day tasks. Your work is supporting everyone else, coaching and nudging a thousand things along. The value that you bring to an organization goes from what you do to who you are.

LC: Do you have a practice as a leader about which you’re particularly proud?

MW: I was recently meeting with some students in the arts administration program at Centennial College. Fabulous, curious young people, they asked me about management training, and I haven’t done a lot of that, but I have done a lot of therapy. I said, “Do you know how much of the family dynamic gets worked out at the office? You think you can run a company without learning how to manage your own family or your own feelings?”

TSO CEO Mark Williams, Yo-Yo-Ma, Board Chair Catherine Beck, and Dr. Laurence Rubin at the TSO’s 100th Gala © Toronto Symphony Orchestra

LC: Speaking of leadership as who you are, in my consulting, I see executive women working in a sea of employees. They are coached to conform to a very safe, predictable archetype. Ironically, they are coming from diverse backgrounds, but soon, they talk in jargon, they sound the same, they dress the same…

MW: So the question should be, what do I bring that’s unique? One can’t bring everything to work. But we can be shades of ourselves.

LC: Because what we’re really after is diversity of thought.

MW: It’s not just diversity for diversity’s sake. Though sometimes it makes people feel good that they’ve done something. But does it move the art or the business forward? It just breeds resentment because it becomes tokenism.

LC: It takes meaningful investment over decades so children are mentored and have access. A propos, let’s talk Toronto. To access many of the communities in our city, you need a car. And most arts organizations miss this strategic piece, because they don’t get out there. So what does that say? Why should these millions of people care? Most aren’t even aware of the TSO’s existence!

MW: An orchestra should not be in Armada. Start with going out to the community and asking the leaders: What do you want from us? What are you proud of that you do or you make out here? What are the challenges? Music builds community. For those two hours in the concert hall, we are a community experiencing the same thing at the same time, feeling the same emotions. When I was in Cleveland, we worked with one community, who at the time was dealing with child mortality issues. We’re not medical professionals. We play violin— we can’t solve poverty. Ultimately, members of our orchestra and composers worked with pregnant women in the community to write lullabies for their children.

At the TSO, we’re working on a project, The Art of Healing, with the Indigenous Healing Institute of CAMH. It started with listening circles, for patients to tell their stories. Gustavo [Gimeno] and I were there along with Yo-Yo Ma, Jeremy Dutcher, leadership from our orchestra and elders from the Indigenous community.

LC: There are a lot of wealthy, successful people in this city coming from all over the world, who, if they were asked, would have a sense of ownership and buy-in for our arts institutions. I want to hold up more civic minded people who give back.

MW: We’re partnering with the Rose Theatre Brampton, their orchestra and youth orchestra, the Rose Buds. We have this project, Reggae Roots, which began as an education concert and will become a community program telling the history of Reggae music and its musicians. Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser, our education and community ambassador, designed the show and it speaks to his Caribbean roots and the richness of this heritage all across the city.

This is a great opportunity to go out and show them who we are. And then shine a light on the music making that’s happening in their own community There’s also a benefit for the business. It’s not about crushing the competition. We don’t want to put the Rose Orchestra out of business. We want more people buying their tickets. Because those people will buy our tickets too.

LC: This flies elegantly in the face of the scar- city mindset omnipresent in our industry. It isn’t zero sum—the money, the donors, the new audiences are out there.

MW: In Cleveland, we invited Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra to play his Swing Symphony. And I remember going backstage and hearing: “I’m really nervous, these people are really good.” And then I’d hear from the jazz musicians, “We’re really nervous, your people are really good!” Artists see each other. And that mutual respect is where great collaborations and new works are born. But you have to bring them together. So as an administrator, as a business person, my job is to create the vessel, and say, “Go for it!”

LC: There is still a divide that I would like to see narrowed between management, admin- istration, and artistic. I campaign for more artists to be mentored into leadership posi- tions because artists can quickly identify excellence. That’s a skill you have developed as a musician that is now bearing fruit as a leader.

MW: I never thought about it, but you’re probably right. You go to the jazz club and maybe you can’t improvise, but boy, that person can. We know how good they are because we know how hard it is. I don’t think you can be effective in running an institution if you don’t care about the product. You don’t need to be a musicologist but you need someone out there who’s conversant, who really cares. I was a horn player but I started answering phones and sending paper press kits, so I’ve seen many different parts of the business on the road to where I am now. That has built understanding, empathy and experience.