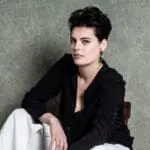

Frédérique Vézina, voice teacher and soprano, talks about unleashing your ‘It’ factor.

When I was 19 years old a teacher asked me why I sang. I told her it was as if I were whispering my most intimate secret into someone’s ear as they slept. And that my secret could go straight to their heart because their mind couldn’t get in the way. How utopian it would be for artists to exist and be received that way, always? Pouring intimate and secret pieces of themselves directly into their spectators’ souls—a communion of sorts. As idyllic as this sounds, I am certain you can think of one or two artists who possess this supernatural ability. They just have ‘It.’ The stage, to them, is where their soul lights a thousand matches so you can peer inside.

Placing profound inner truth above aesthetic beauty of sound has always been important to me. But it’s not that simple. My students might say I’m also passionate about vocal technique, and they are right. There is no way for an artist to dig deep into themselves if they are shackled by their vocal production. Here’s the reality: most singers are highly intelligent artists managing several high-stakes pieces while performing for thousands of people. All at once, their minds and bodies are managing virtuosic vocal technique, complex compositions, stage directions, listening to the orchestra, watching the conductor at all times (down stage or through monitors placed in the wings), making sure they are in their light, handling performance anxiety, all while also attempting to connect to their innermost selves and make their voices transcend the page and reach the hearts and souls of their audiences! The task before any singer, novice or professional, is colossal.

The way we teach singers does not often afford the necessary time for these inner explorations to occur. Educational institutions are there to measure skills and achievements. How would they measure a student’s ability to dig deep into their inner worlds, how would they grade their capacity to bind their newly developed skills to the intangible ‘It’? Furthermore, how can we, as teachers, create that space where our singers learn to stand at the frontier between technical prowess and unrestrained abandon?

The two years I spent at the Juilliard Opera Center (JOC) offered some extraordinary avenues into accessing the depth of our own life experiences. Stage director, Stephen Wadsworth, is attuned to this complexity of stagecraft for singers. I have come to teach my own students how to find connections in their own lives to anchor their singing, as he first taught me. What I’m referring to here is a particular way of digging into our selves to provide even the briefest glimpse of the world as it looks to other, normally very different, eyes. When singers are able to dig into themselves there is always a sense of awe and a particular sacred silence in the room.

Frédérique Vézina in Lillian Alling at Vancouver Opera © Timothy Matheson

Frédérique Vézina as Tatyana in a production of Eugene Onegin at Pacific Opera Victoria © David Cooper Photography

*this text was originally published in the summer 2022 print version of Opera Canada magazine

The key isn’t so much about rising above the technical, it’s about digging deep. Every day at the JOC, we practiced and dug deep into ourselves, like miners digging for gold. We sometimes came out of those sessions with muddy hands and shaken hearts, but slightly closer to that sacred ‘It’. In the studio, I lead my students to unearth nuggets of gold from their past. When a specific experience might have brought them to a state of desperation or hopelessness within themselves. For example, imagine we are asked to empathize with a murderess like Tosca. Our first feeling is likely to be that the woman is utterly foreign to us. Is she suffering? Is she vulnerable? Is she enraged or hysterical? At any rate, she is a figure with whom we have not the slightest connection or relationship. The necessary maneuver then is to draw upon less obvious parts of our own experience. There is in each of us a vast array of life lived that could be in sync with the mindset we associate with a 19th century aristocratic murderess. We might remember one day, late at night on the subway, all alone, being subjected to an unhinged man’s gaze, the putrid smell of his foreign body threatening to defeat our own; or the more universal time we were cornered by bullies in school, humiliated and defeated, as if it were a game to shatter our spirit.

And so, locked away in our memories is the potential to grasp what might be understandable about unleashing fury and facing the world down with an indomitable spirit of defiance to norms, expectations or regulations. In digging into a murderess we are seeking out artistically and detecting an overlap of experience with ourselves. We learn through our art to recognize in so many different characters an echo of our own intimate history.

It is hard work, to be assured. No one aims at opening the proverbial can of worms from the deepest corners of their soul to serve their art. There is infinite vulnerability in exposing the soft parts of ourselves in a world that judges our performances with a scalpel. Perhaps we should ask ourselves what a successful performance is? Is it perfection? Perfect high notes, perfect vowels, perfect body types, perfect casting? Or is it the hair-raising embodiment of the human soul, vocal production that is phenomenal yes, but also gritty and risky and not always perfect?

So where do we go from here, dear singers? Are we to assume that we either have ‘It’ or we don’t? It appears to be instinctive for an elite few. But I believe anyone can develop the ability to tap into their soul and wed it to their artistry. What is the ambiguous ‘It’ we have or lack? The answer lies in our ability to access our own experience in a way that is alive to the darker or less familiar, more distant and sometimes abyssal recesses of ourselves. Regions that we do not access or are not engaged with most of the time; these subordinate bits are the ‘secrets whispered into the heart.’ They can be a little more bold than expected, a little more entitled, surprisingly ugly, violent or euphoric, a martyr and a whore, a thief and a child, when society expects a merely democratic man, a woman, a good guy or a bad guy.

For me, the catalyst for these insights was Maria Callas. There was something unleashed and raw in her singing that left a deep impression. Whenever I listened to her, I felt a sort of fury coming right at me, like a bonfire of distilled emotions. For the quiet introverted child I was, the discovery of such a bold way of existing was seminal. Maria Callas has this power. She brings us back to our emotional lives when we tend to go too far into rational thinking and the dullness of modern life. She sets ablaze the profound feelings we all must keep subdued and controlled in ‘civilized’ society. Maria Callas’s admiring friend Tito Gobbi called her voice una grande vocciaccia (a big ugly voice). I imagine Callas had to give herself permission or even give herself the mission to trample the boundaries of exemplary vocalism in order to become La Divina, the one who could reach into our chests and rip our hearts out.

The singer who hasn’t accessed ‘It’ is rarely refusing the challenge of entering into the experience of a character; rather, they are most often wary of treading with sufficient courage into themselves.

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.