The creators of recent mashups of history and science fiction or literature and fantasy, such as the regrettable film, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, may think they invented a genre. But Handel beat them to it by more than 300 years. Rinaldo, the composer’s first opera for his adopted city of London, which premiered in 1711, takes the real-life First Crusades and the siege of Jerusalem, mixes in a pinch of romance and a hint of betrayal—pretty much standard opera procedure—but then tosses in a few mermaids and an evil sorceress in a flying chariot pulled by a couple of fire-breathing dragons. Hmmm. What’s an opera company to do with that?

Well, if you are Pacific Opera Victoria, you forgo the flying chariot (but keep one non-fire-breathing dragon), play down the point of the Crusades (Christians trying to eradicate Muslims), and play up the opera’s storybook aspects. And it works, with a couple of minor caveats.

Rinaldo—a visual feast

POV’s production (seen Apr. 19), directed by Glynis Leyshon and designed by Pam Johnson, is a visual feast.

The curtain goes up as the overture begins, revealing a typical London streetscape, with four row-houses of diminishing size to the left: identical chimneys spewing identical smoke, an enormous moon hanging above them. The fifth and largest row-house at the right is shown from the interior, complete with staircase to the floor above. A mother and her two pajama-clad children wait for their father to come down that staircase, helmet in hand. It’s 1940, and he is heading off to war.

To help console the children, the mother turns on a giant radio. After they fall asleep and begin to dream, the radio opens like the wardrobe to Narnia and through that magic portal emerge both ordinary and extraordinary beings, including a quartet of Crusaders followed by their leader Goffredo and his noble knight, Rinaldo—who also happens to be the same man we just saw going off to war in 1940.

It’s a clever conceit, and the visual treats continue: dramatically falling flowers that create an instant garden, a black spider that skitters across the face of that huge hanging moon (skilfully used as a screen for a variety of still and moving images), only to turn into the wicked sorceress Armida as she emerges through the portal; a flying ship, and yes, a dragon in Act II, manipulated by four men in black.

Slight visual overload in Rinaldo

It’s great fun, but it does come with a drawback or two. First of all, the children are left on stage throughout, with little to do except wander from one spot to another. More serious, though, was the fact that the strong visuals, by playing up the most outlandish aspects of the plot, made it hard to come back down and recognize a deeply emotional or vulnerable interlude, and sometimes seemed to be there solely to distract the audience from our supposed impatience with lengthy bits where nothing happens, such as the overture and the opera’s many da capo arias.

But these were only minor drawbacks, not deal breakers.

Fortunately, Leyshon understood that there are a couple of arias in this opera that are so beautiful and intricate and wonderfully absorbing, you simply must let the whirling plot stop and leave the singers alone to simply stand and deliver. And they did.

Countertenor Andrey Nemzer a heroic Rinaldo

In the title role, Russian-born Andrey Nemzer is that most unusual creature, a heroic countertenor, able to dispatch incredibly high notes with absolute ease and no diminution of his huge sound. His “Cara sposa,” sung after Rinaldo has seen his true love Almirena kidnapped by the evil Armida, was handled with perfect vocal dexterity. He can act, too, and be silly when required.

As Almirena, soprano Stéphanie Lessard had the fearsome task of delivering one of Handel’s best known and loved arias, “Lascia ch’io pianga,” while dressed in bubble-gum pink tulle and tied up in Armida’s giant spider web. She succeeded, with a pure but still colourful sound.

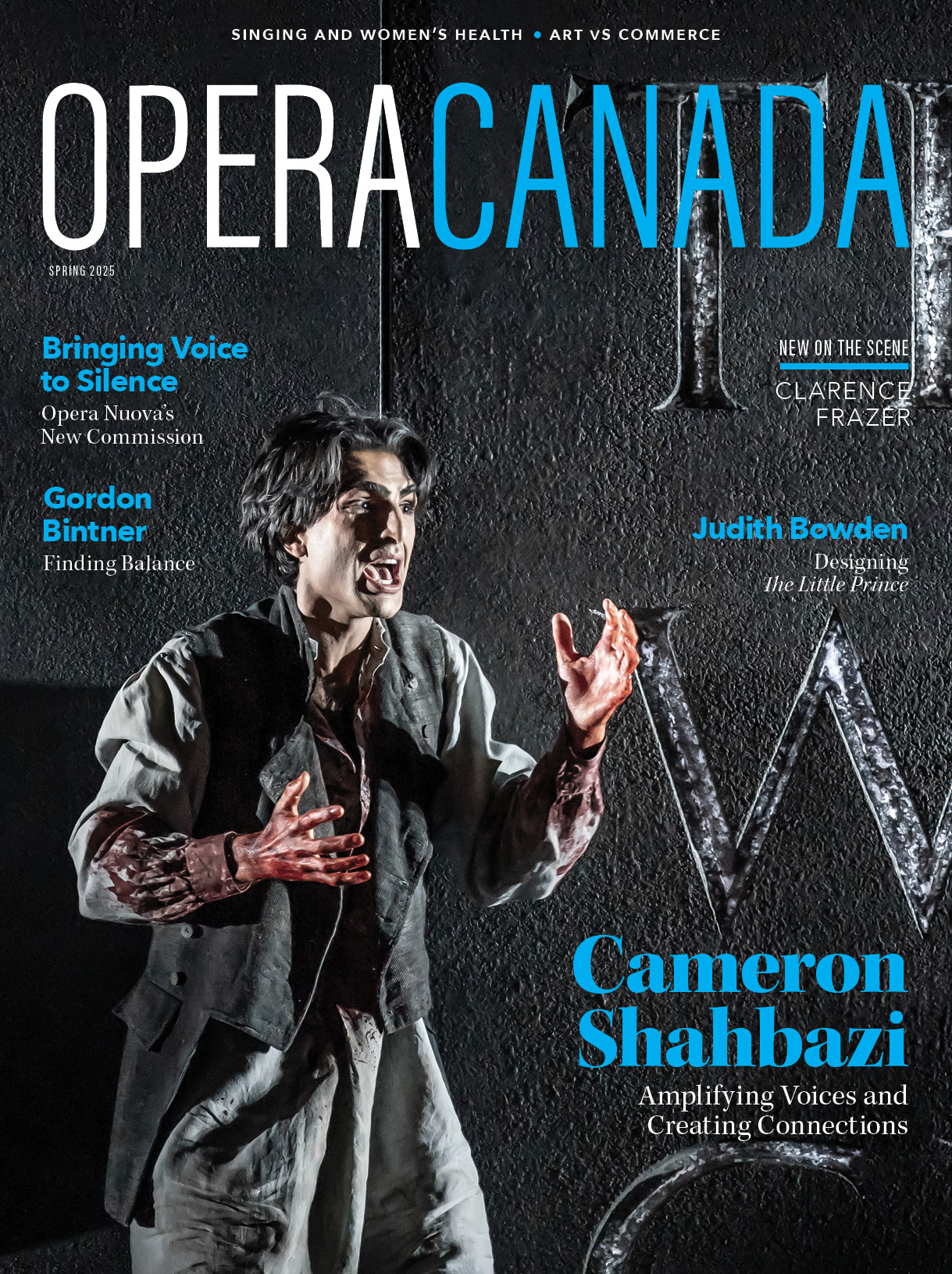

Andrey Nemzer (Rinaldo), David Trudgen (Goffredo) and Stéphanie Lessard (Almirena) in POV’s Rinaldo. Photo: David Cooper

Rinaldo strongly cast throughout

Armida herself, soprano Jennifer Taverner, brought vocal power to a role that required her to be furious most of the time, with just a brief interlude for falling silly in love-at-first-sight with Rinaldo. She handled both extremes well, but could use a little more darkness in voice and body to be absolutely convincing as evil.

As Goffredo, David Trudgen held his own against the power of Nemzer with a very different sound to his countertenor: lighter and sweeter but just as secure. A little more command in his acting would not have gone amiss, though. Baritone Christopher Dunham fortunately demonstrated that command in spades as Argante, King of Jerusalem, filling the stage with energy, as well as an alert, warm, expressive voice.

Conductor Timothy Vernon kept the complex music sure and steady yet lively enough to dance to, but specific mention must also be made of musicians Tatiana Vassilieva on the harpsichord, who garnered cheers for her fabulous harpsichord ritornelli in Armida’s “Vò far Guerra,” as well as oboist Michael Byrne, bassoonist Jennifer Gunter, and the entire trumpet section.