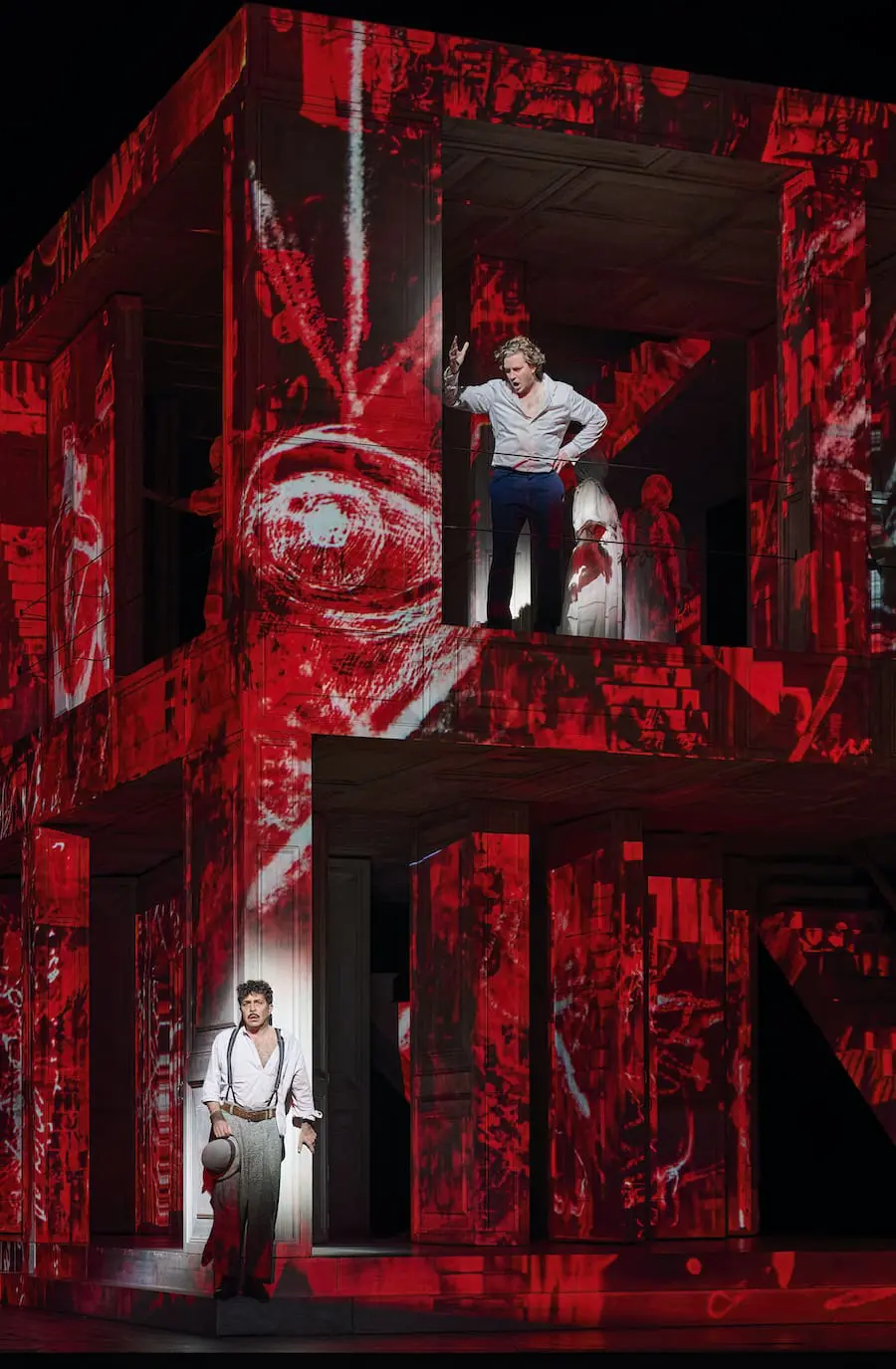

Paolo Bordogna as Leporello (below) and Gordon Bintner as Don Giovanni (above) in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Don Giovanni, 2024

© Michael Cooper

Maestro, the biographical-drama film of Leonard Bernstein released to general acclaim last year, we are presented with a portrait of one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated musical figures, a larger-than-life character whose intensely passionate musicality was sustained, at least in part, by his endless appetite for company, by the presence of others. The Canadian Opera Company’s revival of Kaspar Holten’s popular staging of Don Giovanni (February 2, 4, 7, 9*, 15, 17, and 24, 2024)—spearheaded by Amy Lane—takes a similar angle in its depiction of the eponymous depraved lothario (to be clear, I don’t equate Bernstein with the Don). Put under the microscope here is more than just the (anti-)hero’s sexual appetite: it is his voracious need to be surrounded by people, not just women. Within a split-level stage of doors and hallways, the (sometimes revolving) maze in which he has trapped himself becomes a visual manifestation of a thirst that can never be sated.

Nowhere does this become more viscerally apparent than when the scenery is taken over by Luke Halls’s projections, most strikingly in the swirling vortex of staircases that lead nowhere. Celebrating its tenth anniversary this year since it was first seen at The Royal Opera Covent Garden in 2014, visual effects are the essence of this production, which brings some nuanced interpretation to a perennial favourite that can be challenging to redo anew. The focus is on symbolic representations of Don Giovanni’s vicious cycle: the more he seeks out companionship, the louder tolls the bell of his mortality, sucked into the collapsing hallways of his own fate.

Ghost-like figures lurk silently around corners as omnipresent reminders both of his immoral past and his inevitable demise; names of his global conquests sprawl like a teeming, dissolute family tree. Surrounded thus, he is faced with a list of crimes for which he will be sentenced, not a catalogo of amorous victories. Dripping and splashed liquid alternately reads as blood, ink, or tears, a neat multiple symbolism that carries over into the costumes, too, such as Donna Anna’s black-stained pink dress.

Clever deployment of projections compensates for the fact that often the action onstage and character depth can seem a tad lacklustre. Elements of stage presence were curiously inconsistent: at times, physical and emotional conflicts between characters lacked the necessary violent urgency; at others, it was suitably forceful to the extent that one wall of the set had a minor but audible wobble after poor Leporello was shoved against it. There were some thoughtful uses of lighting the bi-level staging, though, notably in “La ci darem la mano,” with Don Giovanni and Zerlina’s diagonal positioning emphasizing the asymmetrical power in that relationship.

Under Johannes Debus, the orchestra is on fine form at the moment: alert and precise, in tight control and projecting a rich ensemble throughout. Moments of what felt to be pit-stage disagreements over tempi and rubato occasionally reared up, but tended to settle quickly. Gordon Bintner’s Don was keenly powerful, and matched well vocally with Paolo Bordogna’s rich buffo bass capturing the hapless but underrated wit of Leporello. Bintner shone especially in the more forceful passages, while I would have welcomed more consistency in quieter moments, particularly in the seductive “Deh vieni alla finestra.”

Making her COC mainstage début, Armenian soprano Mané Goloyan impressed in Donna Anna’s moments of fiercely righteous grief, particularly in the impassioned Act 1 aria “Or sai chi l’onore,” and displayed a confident control of the demanding sustained lines in “Non mi dir.” Personally, I disliked the disjunction between how Donna Anna’s assault and her narration of the experience were choreographed. I had thought we were rather past the moment where we are comfortable glossing the opening scene as a thwarted seduction, and yet this is how it was played, with Goloyan’s Anna seemingly a willing, but frustrated, lover, not a victim. As she recounted her attack to Don Ottavio later, however, it was rendered with genuine anguish, not with a duplicity that convinces her betrothed. It’s not easy to handle, but is something I want to see addressed with consistent intentionality.

Mozart’s writing for the (non-toxic) male love interests is not among the most exciting in the opera, I’ve always found, but Ben Bliss was a very agreeable Don Ottavio, nicely in control and with a refined tone in the tender “Dalla sua pace.” Anita Hartig’s Donna Elvira always brought an air of regal stature to the role, but a generally powerful and imposing voice slipped around the coloratura, now and then, with a slightly strained edge. Simone McIntosh and Joel Allison made a charming pair as Zerlina and Masetto, McIntosh especially fizzing with energy from her first notes and bringing a nice warmth of tone to both arias, while David Leigh captured well the quiet, stony fury of the Commendatore.

Here, the lieto fine is cut, which offers the remaining characters to breathe a sigh of relief free from the wicked Don, and go about restoring their lives. It’s a perfectly valid choice with plenty of historical basis; a favourite option of nineteenth-century stagings (Romanticism far preferred to languish in the agony of inferno), it suits the dark soul of this production, edging us closer to tragedy than dramma giocoso. I’m of the opinion that it’s unnecessary to pick a side in the “but is it really a comedy?” debate, and I’m certainly no fan of trite endings, but I found it far too abrupt, with bows beginning before the last notes had barely finished. Mozart’s sextet finale can sound rather pat, but it is also dramatically satisfying in a way that felt absent in this case.

If, for Jean-Paul Sartre, hell was other people, for this Don, it’s the opposite. There are no flames or burning brimstone in his final moments on stage, but instead, every door (literally) closes—his total abandonment, a punishment worse than death.

*reviewed on February 9, 2024

Related Content ↘

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.