Canadian Opera Company’s (COC) season-opening presentation of Puccini’s Turandot (seen Sept. 28th) showcased the full force of legendary avant-garde director Robert Wilson’s genre-shattering impact on opera. As much as Wilson’s sparse, hard-edged aesthetic felt deeply at home with Turandot’s bizarre vision of a cruel and otherworldly Beijing—in which the exiled Prince Calaf must survive Princess Turandot’s series of deadly trials before finally melting her heart—it was also starkly alien to what audiences have come to expect from Puccini’s lush and exotic score. It was precisely this dichotomy, however, that allowed Wilson to re-imagine not only Puccini’s opera but opera itself, all the while setting the ideal stage for a masterful musical performance.

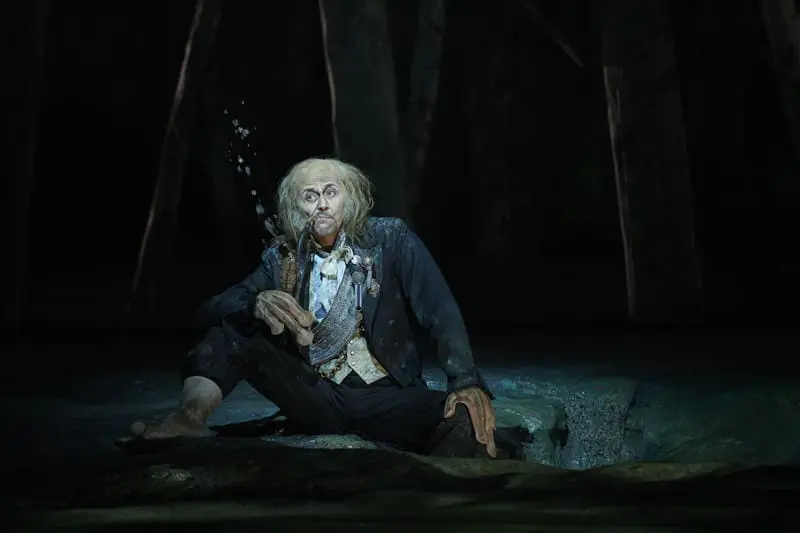

Though minimal to the extreme and intensely hostile to any trace of naturalism, Wilson’s direction was immediately entrancing, immersing its audience in an abstracted world entirely distinct from mundane reality. Singers faced the audience head-on every moment of every scene, holding stiff, squared poses for minutes on end. Dramatic beats were marked with little more than constrained twirls or mechanical gestures. With their faces painted sharp white under grotesquely exaggerated features, the cast looked and acted more like porcelain dolls than people.

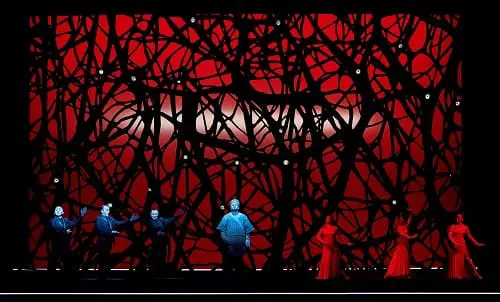

It could be said that Wilson imagines opera as a genre wholly separate from thespianism, allying it instead with the visual arts of cinema, sculpture, and painting. Among the production’s most remarkable aspects was its lighting (also designed by Wilson), whose ubiquitous contrast of ghostly blue-white and deep, piercing red defined not only the opera’s staging, but also its energy and pace. Similarly, Wilson’s no-frills set design offered a masterclass in thrift, as simple, slow-moving geometric shapes accomplished enormous tonal shifts throughout the narrative.

Special mention must be made of the court ministers, renamed Jim, Bob, and Bill—instead of Puccini’s original Ping, Pang and Pong—as performed by baritone Adrian Timpau and tenors Julius Ahn and Joseph Hu. Appearing in distinctly contemporary, black business suits, the trio mounted a crucial self-parody of Wilson’s distinctly austere style. In one scene they emulated the main cast’s stiffness before jauntily hopping around the stage, wobbling their joints like marionettes, laughing at each other as if to mock the narrative as it played out.

Unfortunately, the jesters’ comic stylings—especially those of Ahn and Hu, who were also the only singers of obviously East Asian descent cast in the production—slipped too easily from the commedia dell’arte buffoonery that inspired Turandot to the vulgar racist caricatures of Puccini’s era. Despite production consultant Richard Lee’s call for “an honest conversation” about Turandot’s cultural appropriation and racial stereotyping in official COC marketing materials, the portrayal of Jim, Bob, and Bill (who continued to be co-named Ping, Pang, and Pong all over the official program and in the sung text) did little to substantially address the issue, leaving the opera’s problematic history an alarmingly loose end of the production.

Joseph Hu (Bill/Pong), Sergey Skorokhodov (Calaf), Julius Ahn (Bob/Pang), Adrian Timpau (Jim/Ping) in Canadian Opera Company’s Turandot—Photo: Michael Cooper

On the whole, Wilson’s genius lay in his driving a clean wedge between his aesthetic innovations and the musical prowess of the original score. As a result, the score shone through all the more brightly. Much of this was owed to conductor Carlo Rizzi, who elicited dynamic shadings and expert timing from the COC Orchestra carrying the pace of the opera with impeccable tact.

In the role of Calaf, tenor Sergey Skorokhodov’s guttural, plaintive vocalism and authentic passion suggested a constant struggle to break free of the statuesque poses dictated by Wilson’s aesthetic. Hitting the famous high B of “Nessun dorma” with an enraptured thrust and a distinctly human grain, his voice mirrored his character’s out-of-place-ness in Puccini’s cold fairytale world. However, Skorokhodov had some trouble making himself heard in ensemble, experiencing more success when the stage was ceded to him alone.

This was by no means the case for soprano Tamara Wilson (Turandot), whose crisp, stately tones soared above the orchestra. In consistently achieving a rich, resonant sound, Wilson probably benefited the most from the production’s lack of physical movement, as her stillness only emphasized the incredible power of her unembellished voice. Meanwhile, soprano Joyce El-Khoury gave a rousing performance as Liù, swinging easily through smooth, glassy melodies and soft, echoing high notes that seemed to glide effortlessly from upstage to the house.

Overall, this Turandot felt like an animatronic diorama acting out a breathtaking opera: the craftsmanship was exquisite and the music masterfully produced, but there were no humans here. By fixating on the divide between each character’s physical and vocal presence, director Wilson abandoned the prospect of portraying any kind of connection—or, dare I say, love—between them. For this very reason, however, the subtle revelation of Turandot’s humanness at the performance’s close—though accomplished with nothing more than an awkward smile and the simple embodied motion of breathing—was especially cathartic. For those willing to wait out Wilson’s deft hand, this subtle turn was more than enough to elevate his vision from mere novelty to an astounding reinvention of Puccini’s classic.