The COC‘s Hansel & Gretel (seen Feb. 6th) gives Englebert Humperdinck’s classic 1893 opera a Toronto twist, with benchmark vocal performances and an uncompromisingly creative staging that only rarely misses the mark.

It is difficult to imagine a fairy tale more closely linked to a location than “Hansel and Gretel.” The forbidding forests of medieval Germany and the alluring gingerbread house of the witch are veritably baked into our collective consciousness. For the COC’s Hansel & Gretel, Director Joel Ivany’s vision gleefully subverts these tropes, transplanting the story to a contemporary Toronto apartment building. The resulting set by S. Katy Tucker is a visual feast. The audience views several adjoining apartments in cross-section, each acting as a small stage to propel the plot or provide divertissements as tenants go about their lives. The lived-in atmosphere of each apartment is periodically enlivened by fascinating graphic projections that bring scenes to life like television special effects; particularly enthralling are the kaleidoscopic candy-striping of the witch’s lair and a dazzling scene at the end of Act II wherein the entire set transforms into a scintillating starry night.

The starry night sky projections from Canadian Opera Company’s Hansel & Gretel. Photo: Michael Cooper.

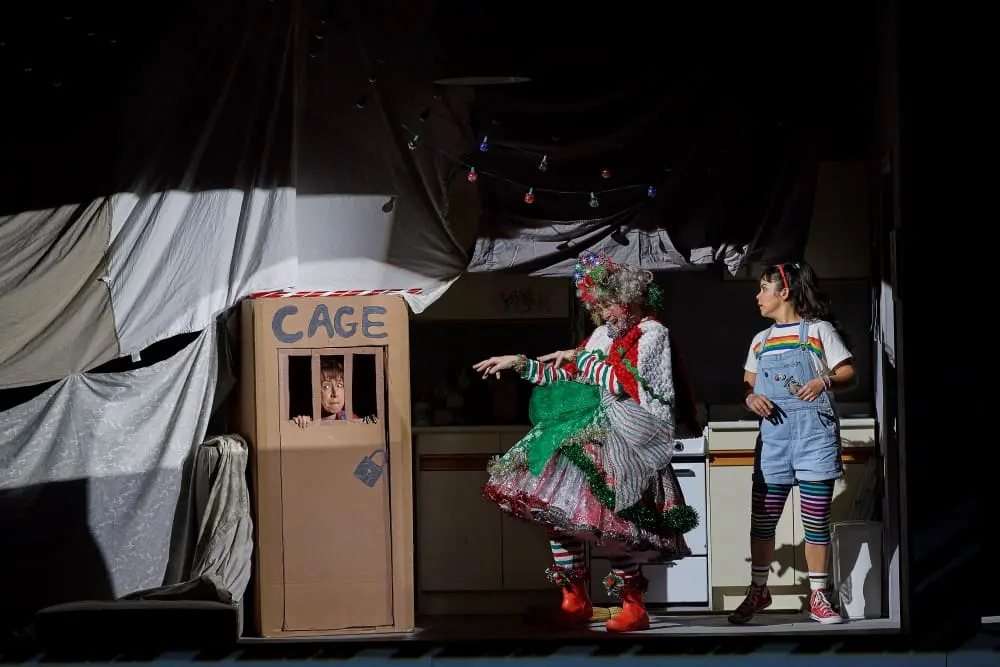

Hansel (Emily Fons) and Gretel (Simone Osborne) are marvellous, their effortlessly childlike demeanour never calling into question their formidable talents as singers. At once individualistic and complementary, their clear and articulate voices rise above the orchestra with youthful ease. In Act II’s “Abendsegen” duet, the two blend with a pure timbre and well-matched vibrato. Their exaggerated physical motions speak to all of childhood’s earnestness and melodrama, and there can be no greater evocation of contemporary youth than the pair’s ‘flossing’ and ‘dabbing’ dances in Act I. The childrens’ father (Russell Braun) also makes a strong impression, delivering robust baritone tone with an unbridled enthusiasm almost matching that of the title characters. Appearing in Act III, the witch (Michael Colvin) is delightfully odious, part slapstick-style clown, part predator. The Irish-Canadian tenor delivers the role (sometimes sung by a mezzo-soprano) with a vocal flexibility that adopts theatrical nasal qualities and whips through certain moments that recall Gilbert and Sullivan patter-style song.

Krisztina Szabó (Gertrude) and Russell Braun (Peter) in Canadian Opera Company’s Hansel & Gretel. Photo: Michael Cooper.

It must be said that the Toronto setting is both a visual masterpiece and a source of some problems for the libretto, which presupposes a Black Forest setting. When Hansel and Gretel sing of gingerbread hedges, they are in the hallway of an apartment building rather than standing before a witch’s front yard. Indeed, the apartment building set is all we ever see on stage, creating some ambiguity about place as the children go exploring. Their encounter with the deep, dark forest takes place in what was, mere moments before, the welcoming home of a friendly senior on top of their own family’s apartment. Even as Hansel and Gretel admit they are lost and frantically shine flashlights into the audience, and even among video projections of skeletal trees, their presence within such a small space undercuts the primal fear of being lost in the expanses of a dark forest.

The setting also creates some mild dissonance against the score and style of the opera. Firmly embedded in the late-Romantic German musical style, Humperdinck’s score owes much to his close relationships with Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss. The harmonic language is dense, with quotations of German folk songs conjuring all the attendant connotations of Oktoberfest and the Black Forest. The Toronto setting introduces a tension, therefore, between the kind of setting the music evokes and what we actually see on stage. COC Music Director Johannes Debus leads the COC Orchestra through the charming and technically demanding score. The orchestra was joined on opening night by five young string musicians from the COC Orchestra Academy, who offered their own strong contribution to the overall polished, flexible, sensitive reading of the score. Debus’ direction is characteristically assured, and the string sections handle the score’s many higher tessituras with grace and precision.

Fairy tales endure because of their ability to take on the forms and anxieties of any age—the libretto for Hansel & Gretel (penned by Humperdinck’s sister Adelheid Wette) itself reflects the Victorian sensibilities of the composer’s time by omitting some of the fairy tale’s more sordid details. In the current production, income inequality and isolation are the topics du jour. The prospect of poverty and hunger bites more deeply when we see it played out in an ordinary apartment building, and the opening video montage drives home the curious nature of high-density housing—so many people leading similar lives, yet never meeting those on the other side of their walls. In the COC’s Hansel & Gretel, Ivany deserves applause for not taking an easy way out, carried by a strong artistic vision, excellent performances, and visuals that will linger in the audience’s minds for weeks to come. If there are occasional misalignments between setting, libretto, and score, it is a small price to pay for an undoubtedly innovative production.