Canadian Opera Company premiered a sensuous and sumptuous, new-to-Toronto production of Rusalka on Oct. 12th. Sir David McVicar’s wildly entertaining staging of Dvořák’s story of a doomed water sprite ranges from the delightfully silly to the profoundly human.

The lush vocals, superb sets, costumes, and choreography make this production a must-see. The design of the forest lake in the opening and final acts is stunning: a dense tangle of trees stretches to the full height of the proscenium, lit in darkly verdant hues by David Finn’s superb lighting design. Wood nymphs, as embodied by the production’s talented troupe of dancers, weave through the forest, thrusting and gyrating sexually as they flirt with the Water Goblin, Vodník, sung by Štefan Kocán. Likewise, a trio of wood nymphs taunt Vodník in song, and while Kocán occasionally sounded strained throughout the evening, Anna-Sophie Neher, Jamie Groote, and Lauren Segal weave their harmonies and tones together beautifully as the nymphs.

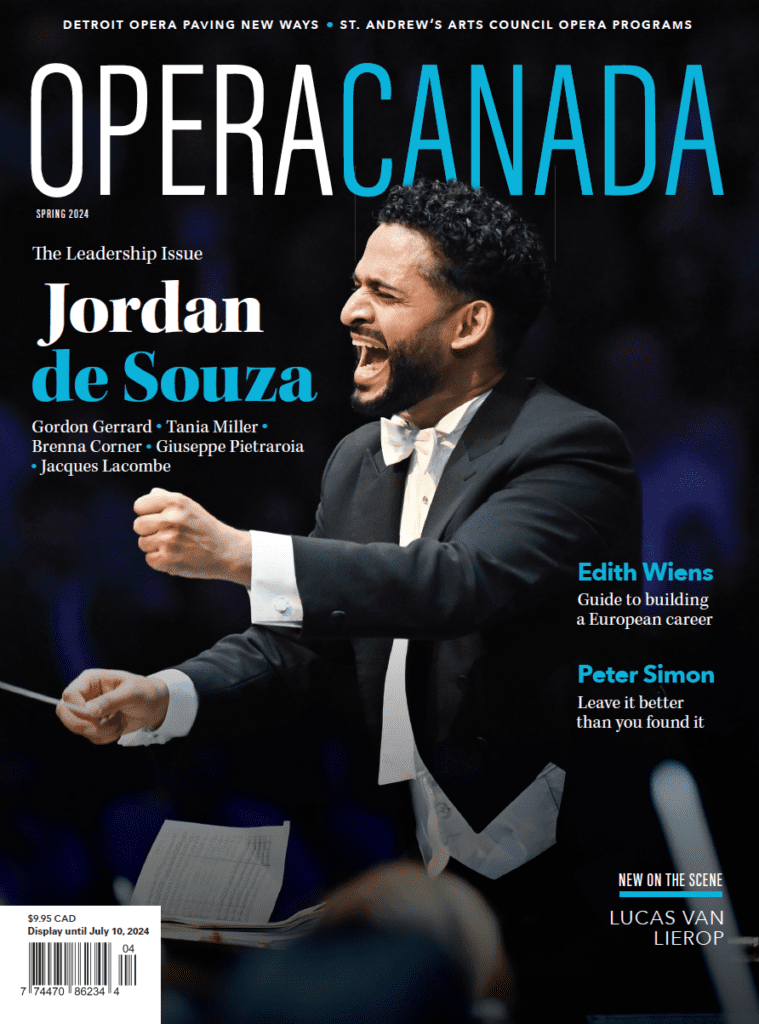

(top to bottom) Jamie Groote as Second Wood Nymph, Lauren Segal as Third Wood Nymph & Anna-Sophie Neher as First Wood Nymph in COC’s Rusalka—Photo: Chris Hutcheson

The power and depth of Sondra Radvanovsky’s impressive voice matches Dvořák’s rich score. In the titular role, Radvanovsky shows off the capacity of her instrument, flawlessly executing the demands of the score with power and grace. She is especially captivating during the opera’s most famous number, “Song of the Moon,” here sung to a massive shimmering moon hanging above the stage. Embodied in her vocalism and physical bearing, the Canadian-American soprano expresses a desperate, and occasionally intimate need for love throughout. While the COC Orchestra under Music Director Johannes Debus executed Dvořák’s atmospheric score very well (despite some minor errors from the horn section during the overture), it didn’t quite match the myriad colours of Radvanovsky’s vocals.

Meanwhile in his COC debut, tenor Pavel Černoch, fresh from performances of Cherubini’s Médée at the Salzburg Festival, sang the Prince with beautifully soft and subtle tone.

The production’s costume design effectively mirrored the contrasting environments of the opera, and Rusalka’s place in them. In Act II, Rusalka appears awkward in her 19th-century ball gown, highlighting how out-of-place she is in the human world. In the final act, as a ghost who is neither human nor water sprite, Rusalka is dressed all in white, establishing her newly liminal existence.

In contrast to the verdurous world of the forest lake, cruelty is subtly ever-present in the human world. Act II opens with a butcher’s blood-splattered kitchen deep in the bowels of the Prince’s castle. The Turnspit comically, but morbidly, stuffs a turkey as the Gamekeeper shares the recent gossip about the Prince and the “creature” he discovered in the forest.

From this grisly basement setting, the Act’s second scene moves to the castle’s luxurious ballroom. Saturated with warm red and orange hues, this transition to the castle’s upper levels provides a lavish backdrop for the opulent gowns and tuxedos worn by the ball guests. Yet even here a hum of dread remains as dozens of taxidermied deer heads adorn the walls behind the posh socialites, evoking the “white doe” that leads the Prince to Rusalka and also foreshadow her tragic end.

This human ugliness, manifest as crass passion, is also present in the choreography. Following the conventions of Romantic opera, a ballet interlude is included, here combining elegant classical ballet with sexual gestures as dancers flash their bottoms mischievously at the guests. Though often comic this vulgarity emphasizes the fickleness of sexual passion, providing insight into the Prince’s eventual infidelity. Human cruelty inevitably encroaches on the forest lake and the life teeming around its shores: a brutalist concrete sewer structure looms from the wings, overshadowing the waters at centre stage. It serves as a powerful symbol resonating with the Witch Ježibaba’s accusation that Rusalka has been “polluted with human passion.”

The production’s dancers are not alone in their masterful physical performance; Radvanovsky embodies Rusalka as a fluid entity, almost constantly in motion during Acts I and III. Elena Manistina as Ježibaba carries herself well as a comic villain, but often resorts to over-the-top gestures which sometimes overshadow her vocal intentions. Vodník, emerging out of the lake and sewers with over-sized webbed hands and feet, evokes iconic 1950s B-films such as The Return of Swamp Thing. The Turnspit and the Gameskeeper, (impressively sung by Lauren Eberwein and Matthew Cairns respectively) act as comic relief, and clownishly stumble and cower in fear when they beg Ježibaba to cure their master, the Prince, of the curse his love for Rusalka has brought upon him.

COC’s Rusalka is one of the company’s most entertaining productions in recent history, balancing the innocence of fairy tales with the deeper truths that often lie at their heart. Beautiful music, stellar singing, and a richly-detailed production make for a most satisfying theatrical experience.

Rusalka runs at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts until Oct. 26th.