SUBSCRIBE TO DIGITAL AND/OR PRINT MAGAZINE

*this text originally appeared in our

2023 fall print issue

On November 6, 2023, we will gather at The Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in Toronto to celebrate the best in Canadian opera. This year we honour baritone Gino Quilico, soprano Isabel Bayrakdarian, music librarian Wayne Vogan, and industry change makers, Jaime Martino and Michael Hidetoshi Mori.

The Rubies: Michael Hidetoshi Mori & Jaime Martino—Change Makers

Lev Bratishenko talks about Martino and Mori’s mission to answer questions of relevance, growth and development in opera through Tapestry Opera’s programs

Why do some opera companies stay relevant while others die slowly and noisily like mammoths in a tar pit? Consider Toronto’s Tapestry founded in 1979 by Wayne Strongman as Tapestry Singers. The company was renamed Tapestry Music Theatre in 1985 and Tapestry New Opera Works in 1999, which tells you that it wasn’t created to be Canada’s neonatal intensive care unit for new opera—but that is what it grew into.

ARE YOU COMING TO THE RUBIES ON NOVEMBER 6?

Join us to celebrate the best in Canadian opera at

The Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in Toronto.

Performances by

Russell Braun,

Midori Marsh,

and Canadian Opera Company Concertmaster Marie Bérard,

all in collaboration with pianist Carolyn Maule.

TICKETS AVAILABLE HERE

This turn was influenced by resident directors Claire Hopkinson in the Nineties and Tom Diamond in the Aughts. Its most famous initiative, the Composer-Librettist Laboratory or Liblab, was launched in 1995: it’s like speed dating to make opera babies. Some of each year’s most precocious crops have excerpts performed at the annual Briefs production.

A list of their dozens of commissioned premieres is impressive but dry reading. The range of subject matter and a focus on contemporary stories, however, distinguish Tapestry today. Important early productions like 1992’s Nigredo Hotel by Nic Gotham and Ann-Marie MacDonald were landmarks for Canadian production, but its plot is abstract, psychological

thriller stuff, while 2001’s Iron Road by Ka Nin Chan and Mark Brownell pointed the way that the company would go.

It’s often telling what the current leadership thinks were the turning points in the history of a company, and for Tapestry

Opera General and Artistic Director Michael Hidetoshi Mori, it was Iron Road. Thousands, many Chinese-Canadian, came

from across the GTA to see an opera about a painful part of their family’s story, when the Canadian government forced Chinese immigrants to pay for the privilege to come here and die working on construction projects. He remembers being in the audience and thinking “how crazy it is that I can sit beside this sixty-something year-old woman from the suburbs who speaks broken English, and we’re sharing something quite profound.”

Later Mori learned that this production introduced Tapestry to a lot of the BIPOC creators they have worked with since.

The opera also preceded the Federal government’s apology for the Chinese head tax by five years. If even a Conservative

government felt it had to say something about the tax, that means public consciousness of the issue was at an extreme at the time, and it’s astonishing that one of the slowest and most complicated arts could produce something relevant years before this peak. An opera easily takes a decade or more to cook (Chan started composing it in 1990), it’s one of the few good excuses for why we expect topicality from some theatre and film, but not from opera.

Contemporaneity takes many forms in Tapestry productions, from stories that include current topics, like today’s so-called

“artificial intelligence” in 2022’s R.U.R. A Torrent of Light by Nicole Lizée and Nicolas Billon; to formal experiments, like

the Tapestry Explorations series of collabs with DJs, physical theatre, punk bands, or classical Persian music and hip-hop in

2018’s Forbidden by Afarin Mansouri and Donna-Michelle St. Bernard; and then there were the productions that offer audiences a way to think and feel together through discomfort. Productions like 2017’s Oksana G about human trafficking,

2016’s Naomi’s Road about the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War, or this year’s Of the Sea

by Ian Cusson and Kanika Ambrose, about Africans thrown overboard during the Middle Passage who survived and now

live in underwater kingdoms.

The thinking behind such programming erases the silly distinction between activism and practicality, and reveals an

interesting dynamic in the company’s management. Tapestry Executive Director Jaime Martino says, ”we accept that our

place is a political one.” So there is no such thing as choosing or not choosing to engage in the politics of our time, and Mori

adds that it’s absurd that opera audiences decline while cities are growing. “That is just slow death. You should be thinking,

wow, what an opportunity to grow our audiences!”

Mori had a solo—“lonely”—position for two seasons after becoming General Director in 2014 and realizing that “we

needed stability. We’d been growing in interesting artistic ways, but organizationally inconsistent ways” which was limiting

their ability to do greater things. The solution was a two-headed animal, influenced by Aislinn Rose’s and Franco Boni’s positions at Theatre Centre. It is telling that Martino comes from a social justice background rather than the world of arts administration, which tends to produce managers good at justifying why something can’t possibly be done right now.

“Administration gets overlooked for the power that it has to shape the way an organization moves through the world and

the impact that it has,” she says.

So a certain structural way of thinking seems important in explaining Tapestry’s relevance. A willingness to say: is your

structure really serving your mandate, your audiences, or your art? Today, the saddest parts of the opera ecosystem are the

big companies trapped in vicious cycles, usually lead by suave dictatorial administrators who say that it’s the audiences who

are conservative, which makes sure that young people and new publics don’t become interested in opera, which makes

the purse power of old guard even more disproportionate, and so on. It’s like watching a caged animal scratch off its own fur.

Since hierarchy tends to uphold conservatism, the codirector model is supposed to preserve criticality by sharing power. Both directors have a peer to question them and someone to lean on. Behind this structure is an unusual board of trustees without a mandatory buy-in donation, and with “a pretty significant portion” of members who had never been to an opera before attending a Tapestry production, says Mori. So the board represents some of the audience they are looking for.

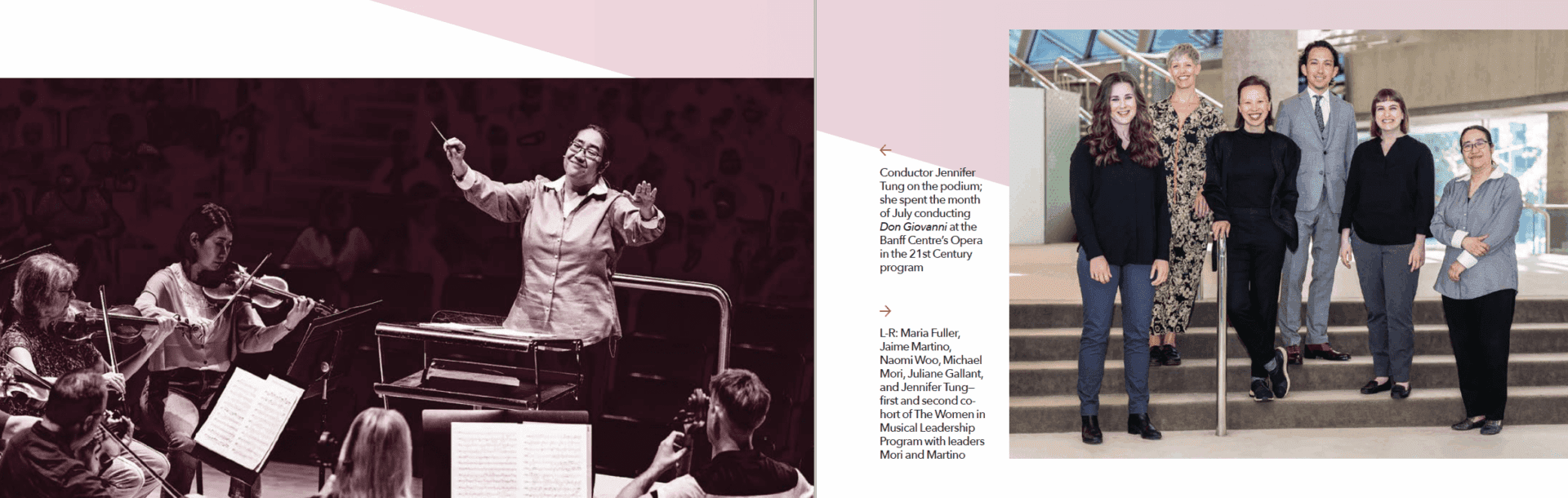

Three years ago, Tapestry started the Women in Musical

Leadership program in partnership with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and Pacific Opera Victoria to redress the fact that less than three percent of music director positions at Canadian orchestras are held by women. One of the major problems is the lack of opportunities in Canada for intense professional practice. The program provides women and non-binary conductors with mid-career mentorships, experience with professional companies, and contacts in the field. It started, says Mori, with a general directors’ conference call where everyone acknowledged the problem and nobody seemed willing to go any further. “I guess we can’t do anything. Okay, see you guys next week!” He laughs.

It would still take two years from that call to find funding to expand the program, but Tapestry could create its own

assistantships right away and that’s what it did. The program has grown with that mix of moral and practical appeal that

seems characteristic of the company’s approach: from eight partners to twenty with a lower cost of entry with each new

organization that joins. The logical next step is to ask, why can’t similar programs redress other kinds of structural issues

in opera, like the racial disparities on and offstage? At the tail end of years of pandemic funding like temporary

wage and rent subsidies, which now looks like the eye in a hurricane, it’s clear that change is coming. Live audiences have still

not returned, and neither have many staff, burned out and hit by inflation. Forced out of their longtime home in the Distillery

District in 2022, Tapestry, in collaboration with Nightwood Theatre—another organization with a shared co-director model,

hmm—and nonprofit developer St. Clares, announced earlier this year a project for a new arts venue at 877 Yonge Street in

Toronto. It is fair to assume that whatever new challenges inevitably arise, the company won’t meet them alone. If your goal is to shift the perception of an entire art form and create the future canon, you will worry about scale. Tapestry might have the budget for a show to run for a couple of weeks, reaching a few thousand fans, many of whom will already know what the company does. It’s a roaring success, in terms of one company, but how much can it shift the overall stereotype of opera? Mori says this keeps him up at night.

“What if we did the perfect show… but what it really needs to do is tour the world?” Film and streaming might help, but

opera just doesn’t scale up very well. The answer may be frustrating, because it’s contradictory. Perhaps, in order to be contemporary, companies have to set themselves impossible tasks. Success—whatever that means—might look like Iron Road happening around the same time as a bigger shift, rather than obviously causing it. Cultural shifts rarely have a single cause but afterwards it’s always apparent who actively participated and who died in the tar. Opera is swinging through such change now. Its future audiences are less interested in arts for its own sake than in art as a way to create a better world. Martino and

Mori are embracing this shift, experimenting in many directions and creating what is needed now, programs like Women

in Musical Leadership. Opera needs many more change makers like them.