Giuseppe Verdi dearly wanted to add King Lear to his string of Shakespeare masterpieces, Macbeth, Othello and Falstaff. While that never came to pass, echoes of Lear abound in his Rigoletto, not only in its themes of treachery and retribution, but also in the presence of a Fool, the timing of a thunderstorm, and the indelible image of an old man mourning the death of his beloved daughter, knowing he was the one who caused it.

Pacific Opera Victoria’s Rigoletto, set in Victorian London rather than medieval Mantua, combines Shakespearean darkness and tragedy with high comedy in telling the story of a father trying to protect his daughter from the debauchery and moral decay that surrounds them. One is more effective than the other.

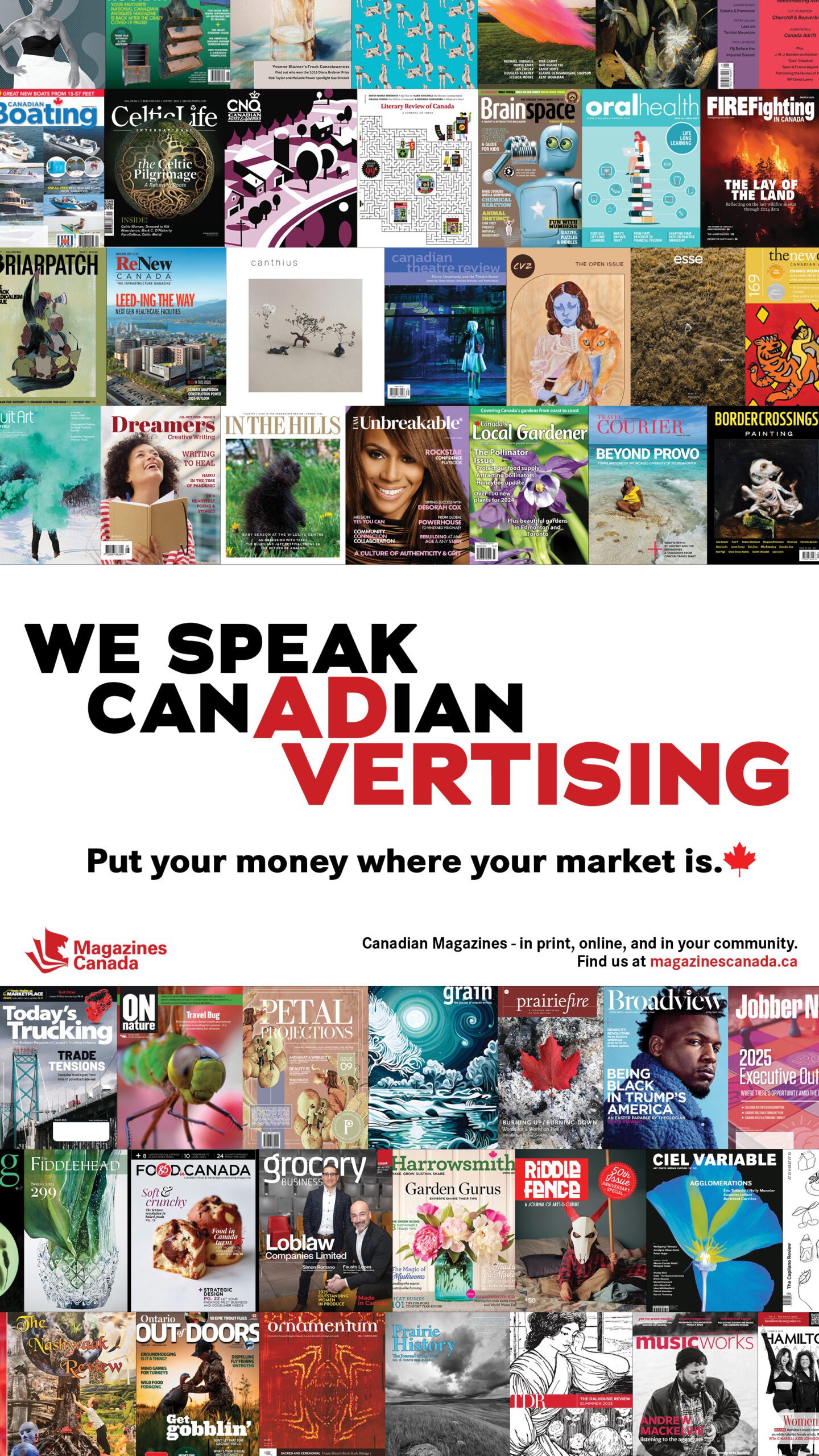

The arrival of the chorus during the overture vividly sets the dark tone. Dressed in black cloaks with eerie white face masks, it becomes clear that these are men who live double lives. On the surface, they are upstanding members of a fine Gentleman’s Club, overseen by the beady eye of Queen Victoria herself, but underneath, they salivate at the appearance of naked women in the painting of an orgy that, with the flick of a crank, replaces the monarch, and they bow to the power of the amoral Duke who rules the club. The servant Rigoletto, who sweeps the club’s floors, is at first happy to cement his place within the Duke’s retinue by viciously mocking Count Monterone, a father whose daughter has been corrupted by the Duke, but the tables quickly turn when Rigoletto’s own daughter, Gilda, is abducted and delivered to the Duke for his pleasure.

A true singing actor, American baritone Grant Youngblood gives his Rigoletto a snarling nastiness that was easy to reconcile with his devotion to his daughter, because they are both equally intense: one adopted for survival, the other springing from love. It is the naturalness of that love for Gilda (sung by Canadian soprano Sarah Dufresne) along with the brilliance of their singing that anchors this production. No matter how much Rigoletto yearns to protect his young and naïve daughter from danger, including odious young men like her new suitor (the Duke in disguise), he is bound to fail, because love also drives his daughter. In the end, she will sacrifice herself to save the dissolute nobleman from an assassin’s dagger.

Though the Duke gets the most famous tune, Youngblood and Dufresne deliver their gorgeous duets with beauty and ease and their solos with heart and craft. In the great second act aria, “Cortigiani, vil razza,” Youngblood’s smooth, rich voice takes the audience on a goose-bump-inducing journey from rage to despair. More goose-bumps break out whenever Dufresne sings. Her voice is silvery, ever so slightly metallic, and her delivery, even of the scariest high notes, is precise, pure and strong. She is a major talent, and the audience, electrified, knew it.

Photo Credit: David Cooper Photography

The Duke (Matthew Pearce) and Sparafucile (Matthew Treviño)

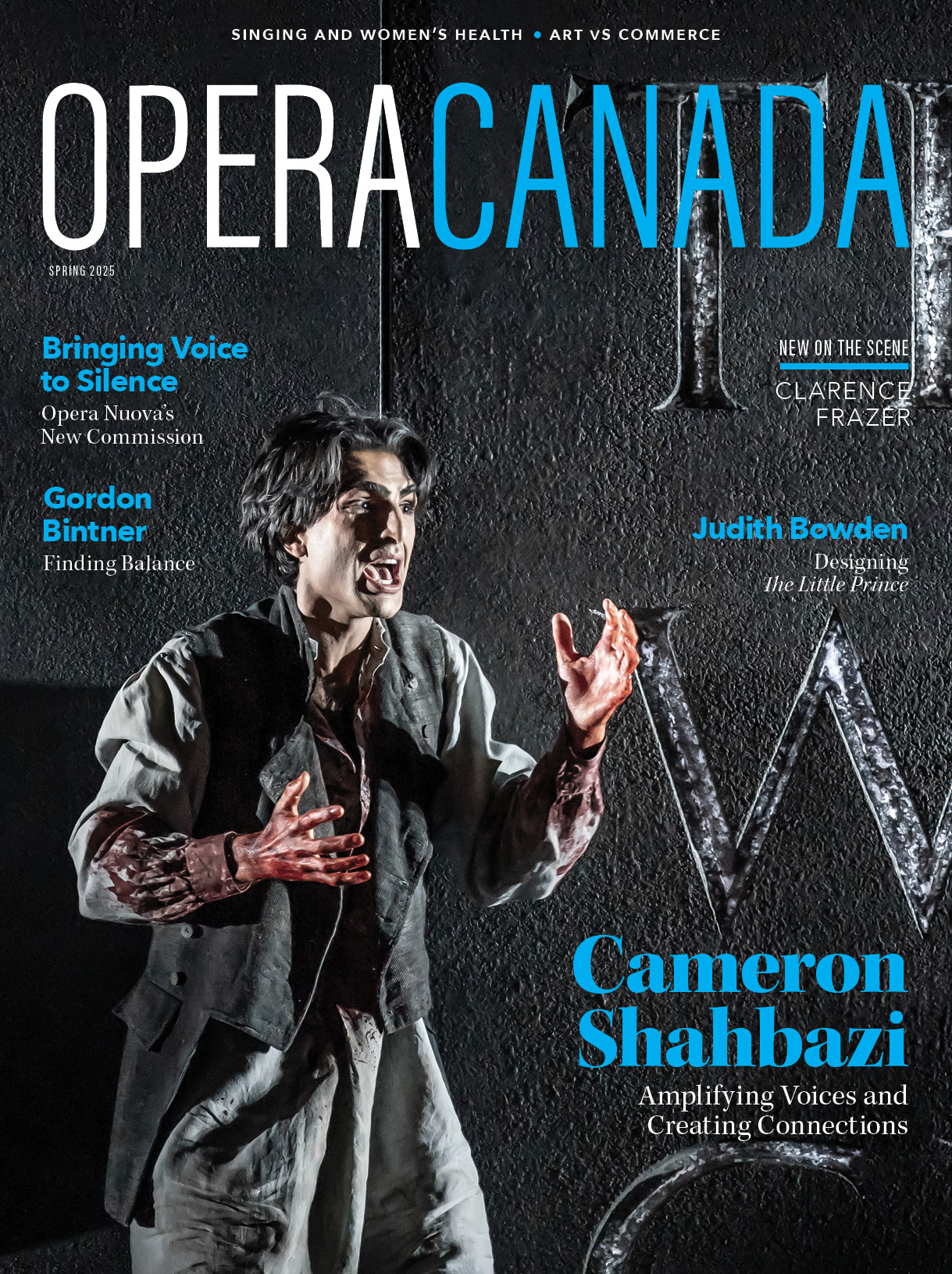

American tenor Matthew Pearce has a well-nigh perfect voice for the Duke – firm, clear, and bright – and his arias were exceptionally well delivered. But his “La donna è mobile” did not, as the best renditions do, stop the show. The Duke requires large doses of both charm and swagger. He may resort to rape when needs must, but most of the time he doesn’t need to, and the audience adored him even as he rebukes women for the sins he cheerfully commits. Of course, that has a lot to do with this wildly catchy tune, but pushing it over the top also requires commitment to character.

Bass Matthew Treviño hit fabulously low notes as the assassin Sparafucile and was chilling as he honed his blade while waiting for Rigoletto to pay him to kill the Duke. Mezzo Marion Newman’s Maddalena proved a sexy partner for the Duke as he quickly gets over his brief flirtation with maybe, possibly, perhaps, feeling true love for Gilda. The rest of the main cast, including James Demler (Count Monterone), Justin Welsh (Marullo), Jan van der Hooft (Matteo Borsa) and Andrew Greenwood (Count Ceprano), were solid. The all-male chorus was downright magnificent, and the orchestra, under Victoria native Robert Tweten, handled the opera’s sometimes startling changes in musical tone with precision and dexterity.

There were, however, also a couple of missteps in this production. It’s easy to see the allure of a Victorian setting, and both James Rotondo’s black-and-white set and Pam Johnson’s costumes are visually effective. But a men’s club janitor with a broom and a limp is not the same as a hunchbacked court jester (as intended by Victor Hugo, who wrote the play on which Verdi and librettist Francesco Maria Piave based Rigoletto). One is infinitely more pitiable and poignant, and it’s far easier to understand the animus of the Duke’s courtiers toward Rigoletto as a savage-tongued, equal-opportunity jester than as an insignificant servant. And at the very end of Act Three, director Glynis Leyshon’s decision to have Gilda rise immediately from her death bed as a spirit unfortunately robbed Youngblood of the attention he deserved in his great, Lear-like tower of grief.

But in the end, these are mere quibbles. (Though I will add one more: the slapstick elements in Act Two felt jarring, with servants out of an English farce and Gilda’s evil gang of abductors behaving like Keystone Cops. For me, the comedy in Rigoletto needs to be subtler.) On the whole, however, this is an accomplished and assured production of a great classic. It deserved the enthusiastic and sustained standing ovation it received on opening night and no doubt will continue to receive throughout its run.

Photo Credit: David Cooper Photography

Rigoletto and the Duke’s confidants confront Count Ceprano in Rigoletto at Pacific Opera Victoria

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.