Massenet’s Werther (seen at Oper Frankfurt on Dec. 30, 2017), based on Goethe’s epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther written in Wetzlar near the author’s native Frankfurt, is one of those timeless operas which has enriched the coffers of opera houses the world over for well over a century. Much of the opera’s success can be attributed to pages upon pages of beautiful music, though one could argue that the protagonist’s Act IV death scene goes on for far too long.

Timely it was that Oper Frankfurt revived Willy Decker’s staging of Werther this past December, considering that the opera’s climactic moments occur on Christmas Eve.

Classic Willy Decker production of Werther

Decker’s production, seen at its 30th performance at this house, also had a timeless quality, though not always in the best sense of the word. According to the score, the action takes place “between July and December,” a point that Decker and his set and costume designer Wolfgang Gussmann ignored. Either that or they felt that the weather in Werther’s Wetzlar ought to be the same in summer as in winter since none of the characters wore anything but period dress suitable for winter. Perhaps those one or two snowflakes which occasionally floated down from the gantry prior to the Act IV Christmas Eve snowstorm weren’t so stray after all.

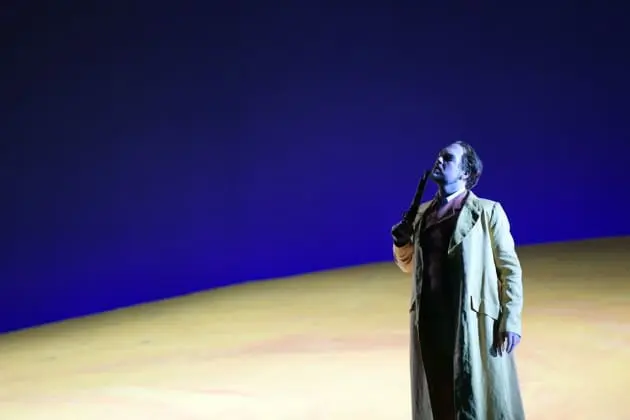

Joachim Klein’s lighting did help differentiate the seasons by establishing the opening act’s summer season with its sunny, yellow light, and the darkness of the final act’s winter night with ominous shadows being cast about. Further in the deuxième tableau of Act IV, neither Werther nor his costume showed any signs of a fatal pistol shot, the character even rising from a prone position to walk about extensively while singing before finally succumbing to his invisible wound. Alas, Decker gave away the opera’s ending when he had Werther stand with his back to the audience and a pistol to his head in a clichéd pantomime which played out during the first bars of the Act I Prélude. Decker also had Acts 1 and 2, then 3 and 4 play without break which deprived the Frankfurter Opern- und Museumorchester of much needed opportunities to re-tune.

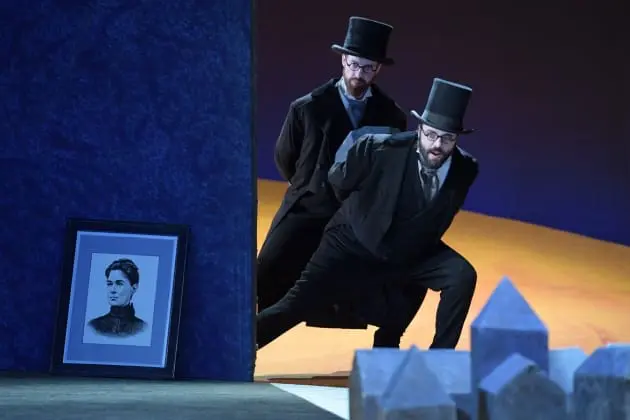

As for set design, this was a minimal Werther. A raked stage with a sliding, perpendicular divider wall, chairs, tables, a painted portrait of Charlotte’s late mother, Christmas carol sheet music for Charlotte’s seven younger siblings, Styrofoam miniature buildings and a pistol were all the trappings Gussmann provided.

Attilio Glaser was a convincing Werther, but vigorously pushed out high notes such as the A on the word “ciel” in Act I.

Julie Boulianne a memorable Charlotte

Canadian mezzo-soprano Julie Boulianne’s plummy tones and impeccable French made her a memorable Charlotte. The Letter Scene was a tour-de-force, Boulianne using a palette of varied hues.

Bass-baritone Franz Mayer sang an impeccable Le Baïlli with a firm vocal tone.

Sebastian Geyer’s brooding Albert added a weightiness to his scenes.

Louise Alder was a suitably pert Sophie who could produce ringing high notes such as the high A on “heureux” in “Du gai soleil,” eight bars after having sung “que Dieu permet d’être heureux” with hushed, straight tone.

Schmidt and Johann, Peter Marsh and Barnaby Rea respectively, at first acted as an anachronistic version of Dupond et Dupont from Tintin. As the opera progressed, they became Puck-like, going so far as to be totally involved in the handing over of the pistol near the opera’s close. Vocally, Marsh was sharp on the lower notes of Schmidt’s arpeggios in the line “De bénir le Seigneur.”

Six singers from the Nikolaus Henseler’s Kinderchor der Oper Frankfurt began “learning” the new Christmas carol using suitably screechy voices, before sounding like angels in the “finished product.”

Constantin Neiconi as Bruehlmann, Jianhua Zhu as Kaethchen, as well as their colleagues in the Chor der Oper Frankfurt as the townsfolk had no difficulty with their roles.

Overpowering orchestra

In the pit, Hartmut Keil paced Massenet’s score quite well, but his oversized gestures could never draw a hushed piano let alone a pianissimo from the orchestra after the heavy rinforzando in bar 10 and elsewhere. Several times, Keil let the orchestra get away from him and cover the singers, one such spoiled spot being the fortissimo passage at Werther’s Act I line, “Sans que nul à son tour les contemple un moment!”