It’s no mere tilting at windmills that Mozart’s Don Giovanni, rising from its own grave 231 years since its premiere in Prague in 1787, shudders with even greater resonance in today’s brave new #MeToo world, where modern day moguls fueled by their own narcissistic power and appetites eerily echo opera’s quintessential bad boy and continue to prey on vulnerable women.

Manitoba Opera opened its 46th season with the Wunderkind’s two-act dramma giocoso, composed to Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto, in turn inspired by the legend of Spanish nobleman and libertine Don Juan. It’s astonishingly only the first staging of the classic by the company since 2003, with this latest incarnation directed by award-winning Spanish-born director Oriol Tomas marking his MO debut.

Hipster-vibe costumes from Edmonton Opera, as well as a wonderfully imagistic, tiered set of a skeletal bullring evokes past glory—and gory—days of blood-soaked bullfights, or alternatively a non-specific, burnt-out shell akin to Rome’s Coliseum, effectively lit by Scott Henderson’s saturated blue and red hues, further heightened by billowing stage smoke.

MO’s Music Advisor and Principal Conductor Tyrone Paterson led the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, as well as the Manitoba Opera Chorus (prepared by Tadeusz Biernacki) during their brief stage appearances with customary finesse.

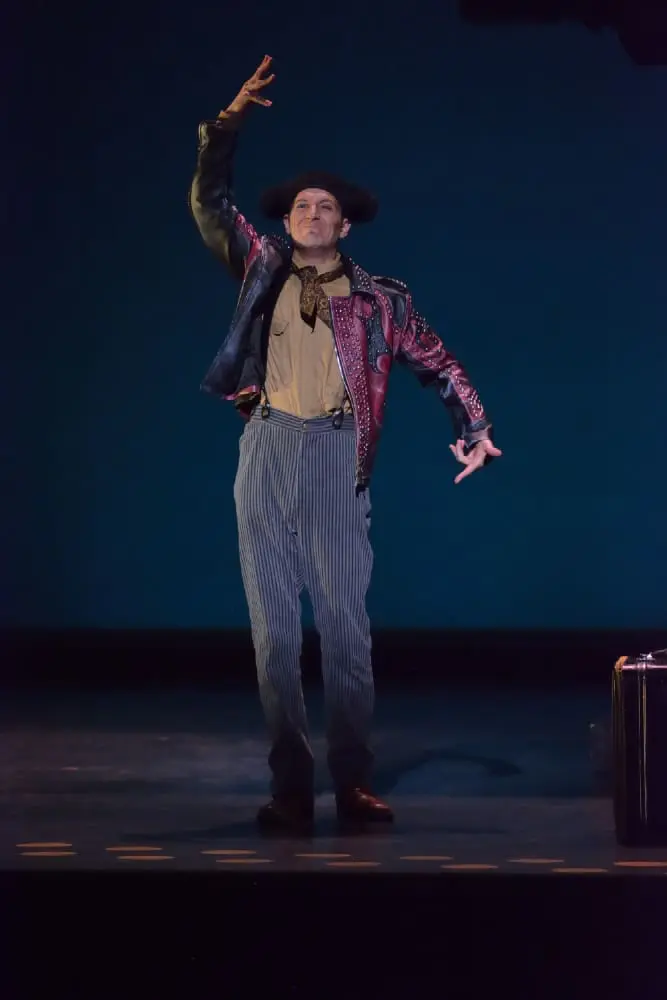

What makes this production sing are its two male leads. Canadian bass-baritone Daniel Okulitch who last appeared on the MO stage as Count Almaviva in 2015’s The Marriage of Figaro, electrified the Nov. 24th, opening night audience with his signature portrayal of the title role he has now performed dozens of times worldwide. His morphing into a swaggering, flask-swilling matador injected its own potent commentary on the increasingly controversial Spanish rite of slaying beasts for sport, as well as the ever-raging cult of deified celebrity.

Okulitch displays a no-holds-barred embodiment of the Don’s deepest, most volatile desires, striking haughty, toreador poses punctuated by whip-cracking foot stomps, as well as oozing charisma during his serpentine seduction of the female prey caught in his bull’s-eye crosshairs.

His wheedling of Zerlina (soprano Andrea Lett) during Act I’s wedding scene, quickly escalates to full-on sexual assault, which juxtaposed to Mozart’s genteel orchestral accompaniment is the stuff of nightmares—kudos to both these strong singing-actors for their unflinching realization of the stomach-churning narrative.

Okulitch’s richly resonant vocals, clear diction and agile phrasing were displayed in his trip-off-the-tongue recitatives, and rapid-fire delivery of ‘Champagne Aria,’ “Finch’han dal vino,” as effervescent as a glass of bubbly and contrasted by a lushly romantic “Deh vieni alla finestra,” as he woos Elvira’s maid.

Canadian bass-baritone Stephen Hegedus easily holds his own against Okulitch’s bravura performance as long-suffering valet/sidekick, Leporello. He creates oceanic riptides of sub-text as he rails against, reveres, and finally, triumphantly wrests power during the brilliant final image as his master perishes in hellfire. His biting into an apple as forbidden fruit packed its own emotional wallop; a singular moment crafted by Tomas’s sensitive direction that also included numerous, compelling stage tableaux, including one invented for the overture where “Don G” puffs and preens in full matador regalia.

Hegedus’s spot-on timing had the audience in stitches in Act II’s opening scene, where he disguises himself in Giovanni’s sartorial jacket, as well as with his ‘catalogue aria,’ “Madamina, il catalogo e questo,” in which he nonchalantly lists Giovanni’s conquests to a gaping Elvira.

The production also showcased three Winnipeg born, bred, or based sopranos each embarking on their own character’s respective journey, albeit with a few minor bumps along the way.

Now based in Europe, Jessica Strong (who last appeared here 10 years ago in the MO Chorus ranks), made an auspicious company debut as soloist, commanding the stage with her charismatic stage presence and lusciously warm vocals, including gleaming top notes displayed during her major arias “Or sai chi l’onore Rapire a me volse,” and later, a limpid “Non mi dir.”

Jessica Strong (Donna Anna) and Owen McCausland (Don Ottavio) in Manitoba Opera’s Don Giovanni. Photo: Robert Tinker

Strong navigated her role’s treacherous vocals including its notorious, florid coloratura, with a well-paced performance, including the eye-of-the-storm trio “Protegga il giusto cielo” sung with Don Ottavio (tenor Owen McCausland) and Elvira in which they plead for heavenly protection. The singer also created fascinating sub-text, showing Anna torn between lust and revulsion for Giovanni.

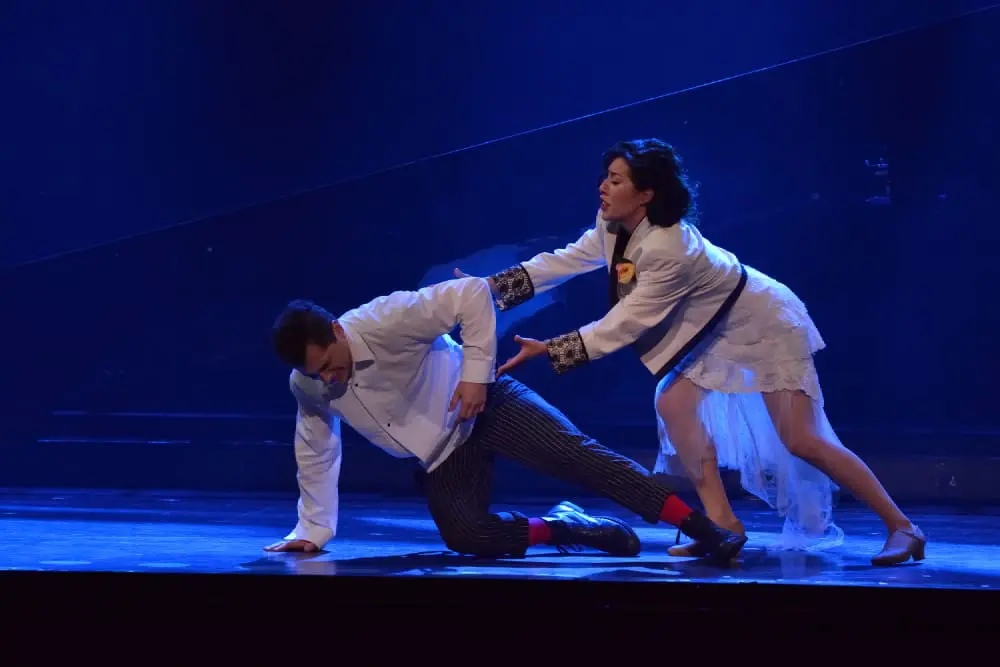

Lyric soprano Monica Huisman crafted a wildcat Elvira who becomes the moral checkpoint of Giovanni’s existence, bringing bushels of energy to the stage with her indignation, at times so heightened that it caused slight intonation issues with her uppermost range. This powerhouse delivered “Ah, chi mi dice mai,” with the fury of a woman scorned, and even more forcefully, her subsequent “Ah, fuggi il traditor” in which she thwarts Giovanni’s initial seduction of Zerlina that also showcased her innate dramatic flair.

Monica Huisman (Donna Elvira) and Daniel Okulitch (Don Giovanni) in Manitoba Opera’s Don Giovanni. Photo: Robert Tinker

Last but not least, Andrea Lett’s lighter, albeit crystal clear, assured lyric soprano voice nailed each of Zerlina’s arias, including (mercifully) injecting dramatic irony into “Batti, batti o bel Masetto,” in which she invites husband Masetto (baritone Johnathon Kirby) to beat her for being tempted by Giovanni, as well as “Vedrai carino,” flipping the narrative on its head as she seduces Masetto.

American bass Kirk Eichelberger instilled gravitas into his ghostly Commendatore, booming “Don Giovanni! A cenar teco m’invitasti,” directed at an increasingly defiant Giovanni. The Act II cemetery scene, in which tombstones are replaced by hanging, severed bulls’ heads created an arresting trompe–l’oeil, with (depending on sightlines) Giovanni’s own human skull seemingly replaced by that of a hulking beast.

Johnathon Kirby (Masetto) and Andrea Lett (Zerlina) in Manitoba Opera’s Don Giovanni. Photo: Robert Tinker

Tomas (wisely) chose to omit the final ensemble typically performed since the early 20th century, in which the cast reappears to deliver its moral lessons. However, the original finale still felt oddly anti-climactic. All-too-brief pyrotechnic effects felt less flaming-tongues-from-hell, than nifty special effects borrowed from your latest rock concert. And a rafter-shaking voice like Eichelberger’s really doesn’t need to be amplified—that frankly cheapened the scene—while the female demons that suddenly flounce onstage to disrupt the power dynamic between Giovanni and his women feel far too Canadian-polite.

Having said this, kudos to Tomas and his committed cast for bringing Mozart’s perennial classic to life, more resonant today than ever. The audience leapt to their feet at the close of the 175-minute (with intermission) production, delivering the ultimate accolade to Okulitch during his own curtain call: loud jeers and boos that he lapped up with relish, proving that Giovanni had seduced even these 21st century savvy listeners with his seductive power and nefarious ways.