“In the fall of 1946, an unprecedented and unique form of instruction was introduced into the curriculum of the newly organized senior school of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto.” Opera and the University of Toronto, Kenneth Pegler

Developed by its first director, Arnold Walter, the Opera School, now the Opera Division of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, has had an enormous influence on the musical life of Toronto, of Canada and the world at large.

As Pegler noted early on in his study: “The performances of the ‘Opera School’ were by no means the first of their kind in Canada. Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia played to pre-Confederation audiences in Quebec City in 1864.” Musicologist and former Dean of the Faculty of Music, the late Carl Morey, noted in his program note for the Opera School’s 1974 production of Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore that an Italian touring company had previously presented the opera to the good citizens of Toronto in the late 19th century, and the city hosted numerous touring opera companies in the early decades of the 20th century.

Like many North American cities of the time, Toronto had several opera houses, many of which were subsequently destroyed or torn down. (Interested readers can glean more information from Joan Parker Baillie’s excellent Look at the Record: An Album of Toronto’s Lyric Theatre, 1825-1984.) The historical record tells us that these theatres were only rarely used for opera. Instead, they were often pressed into service for vaudeville and various other touring attractions.

In Montreal, things were a bit more vibrant. The Montreal Opera Company produced 13 works between 1910 and 1913, including Carmen and La bohème, the latter less than 20 years after the opera’s premiere. The personnel of those productions—both artistic and administrative—were imported from outside Canada.

In 1928, Sir Earnest MacMillan, principal of the Royal Conservatory of Music of Toronto formed an ad hoc opera company which, although under the banner of the RCMT, presented works in the unlikely venue of the newly opened Royal York Hotel. The company offered unusual repertory, such as The Sorcerer by Arthur Sullivan and Hugh the Drover, composed only four years earlier by Ralph Vaughan Williams. But within two years, Toronto and its conservatory had been badly battered by the depression and Sir Earnest’s company reluctantly ceased operation.

Opera in Toronto would remain dormant for five years till, in 1935, the Opera Guild of Toronto endeavored to establish a company that would provide operatic entertainment to the city while affording opportunities for Canadian artists. The guild’s objectives were straightforward:

[1] To afford facilities to Canadian singers for engaging in the singing of opera, thereby giving a breadth of character and color to their training which is not otherwise obtainable in Canada.

[2] To create and develop in singers and in the general public a genuine appreciation of operatic music and the technique of opera.

[3] to develop an organization of Canadian artists capable of producing all-Canadian presentations of opera.

[4] to present operas from time to time, casting as much as possible from Canadian singers.

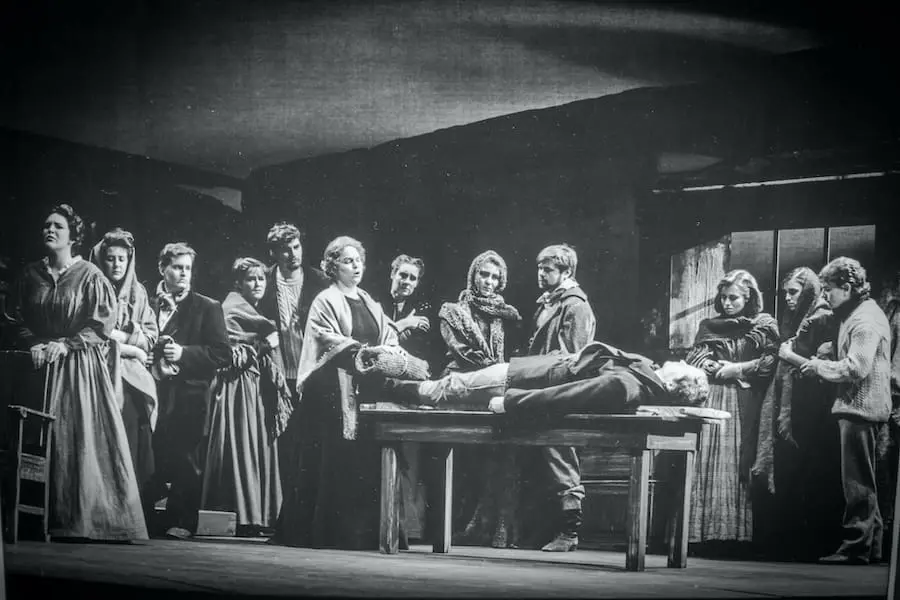

Soprano Adrianne Pieczonka (left) and company in the 1988 staging of Vaughan Williams‘s Riders to the Sea Ⓒ COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

The historical record tells us that within their four years of existence, the Guild presented remarkably sophisticated seasons that included such works as Tosca, I pagliacci, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin. Utilizing the original four objectives of the Guild, augmented by a report commissioned from Ernest Hutcheson, then president of the Juilliard School of Music in New York, plans emerged to revamp the senior school of the Royal Conservatory of Music. Out of that reorganization emerged, under the artistic guidance of Dr. Arnold Walter, the “Opera School.”

But before we get into the nitty gritty, it is worthwhile empathizing something extraordinary about the arts in Canada, which is that training for the performing arts is almost as old as the performing arts themselves.

Consider the National Ballet of Canada. Ballet lovers in Toronto, anxious to create a professional presence, wrote to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, specifically to famed ballerina Ninette de Valois. These visionaries asked her advice; they needed a pioneer to create ballet in Canada out of whole cloth. Madame de Valois sent them her best and brightest, Celia Franca. She put her toe shoes to the grindstone and the National Ballet of Canada was established in 1951. Eight years later, in 1959, we had the National Ballet School.

Ditto, the Stratford Festival. Founded in concept by the Shakespeare-loving reporter, Tom Patterson, it officially opened on July 13, 1953, with a production of Richard III, starring Alec Guinness in the title role. Repeating the pattern of the ballet, the National Theatre School opened its doors eight years later.

The Opera School of the Royal Conservatory of Music, ultimately absorbed by the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, is a stunning reversal of that process; the Opera School, essentially an educational institution, would ultimately branch out and become the Canadian Opera Company.

So let us get into the time machine: Our voyage begins with Arnold Walter, who was born in Czechoslovakia, pursued his musical studies in Berlin, and then emigrated to Canada when Hitler came to power. Initially engaged at Upper Canada College, he later joined the Royal Conservatory of Music, ultimately becoming director of its senior school, which housed the newly formed opera school.

In Walter’s own words: “The Opera School… serves a double purpose: as a school it undertakes to train young singers and to make them familiar with all phases of operatic production; as an operatic company it presents those artists so trained… without the training afforded by the school, all-Canadian performances would be an utter impossibility; without seasonal productions, the training itself would be pointless”

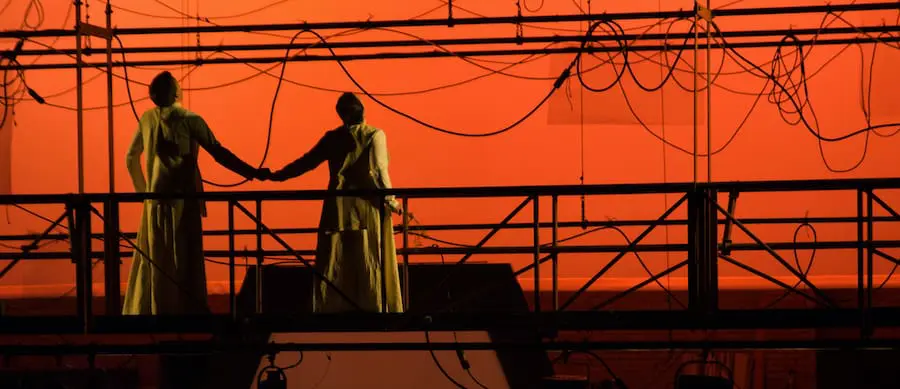

Scene from a 2016 student- composer project to make E. M. Forster‘s The Machine Stops into an opera

In a similar vein, Nicholas Goldschmidt, the school’s first music director, also came from Europe and arrived in Canada following initial immigration to the United States. Excited by the opportunity to be part of the creation of a new performing arts program, Goldschmidt was thus lured away from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Reflecting on his new life in Canada and the future of the Opera School, he wrote: “… if the opera school produces just one excellent singer each year, then it is well worth the effort and the expenditure.”

Goldschmidt would set a high bar, admirably sustained by subsequent music directors; Ernesto Barbini, James Fraser-Craig, Stephen Ralls and Sandra Horst.

The very first performances of the Opera School were given at Hart House Theatre on the University of Toronto campus, to this day a thriving, theatrical venue. Walter recorded his remembrance of that performance in his diary: “I knew on the night of December 16th, 1946, when we presented our first performance of excerpts… an uninterested observer would have found the settings primitive, the costumes humdrum and the lighting crude. What was it that aroused so much enthusiasm among those who saw the show?”

Felix Brentano was the opera school’s inaugural stage director. A student of the celebrated Max Reinhardt, he initially established his professional career in the Broadway commercial theatre and, astoundingly, commuted to Toronto for three days each week from his home in New York to supervise rehearsals. Walter remembered him as a gifted, imaginative artist, though not without temperament. “I had never seen anything like Brentano’s staging of Orpheus and Euridice, particularly the mask scene. At centre stage stood singers in a cluster, each of them wearing gloves to match their golden masks. But the gloves didn’t match and Brentano, who got very upset by such things, came to me and said: ‘This is impossible. We can’t perform this thing with those gloves! They’re just not right.’ So we stayed up all night dyeing those gloves gold. And after that, of course, we couldn’t use them for anything else, so I kept them and used them for my gardening gloves for the next 15 years.”

Brentano was succeeded by Herman Geiger-Torel, who in 1938 left the oppressive political climate of Germany for South America, where he ultimately became the director of Rio de Janeiro’s Municipal Theatre. Geiger-Torel’s vast directorial and teaching experience made him the ideal candidate to create a curriculum that stressed not only musical development but also the honing of dramatic skills, including movement, stagecraft and role interpretation. He also recognized that public performances of complete operas were essential to the development of operatic artists.

“As the school expanded, the budget requirements increased sharply,” Pegler wrote in his history. “The school needed $10,000 for their production of The Marriage of Figaro. Dr. Walter went to the president of the university, Sidney Smith, to ask for the money. Dr. Smith was less than sympathetic, explaining that universities ran on public funds which could not be used for ‘show business’ enterprises. Private assistance had to be found, and soon guarantees were forthcoming from such personalities as Lady Eaton and Vincent Massey.”

Those historically important Figaro performances took place before capacity audiences at the fashionable Eaton auditorium. Not only were productions becoming more sophisticated and Canadian singers given opportunities, but adjunct musicians were developed as well. The La bohème house program of the time tells us that the production’s musical coach was George Crum, groomed to become the conductor of the National Ballet, and the concertmaster was Victor Feldbrill, later to take the reins of the Toronto Symphony.

Besides encouraging promising artists such as Jon Vickers and Mary Morrison towards operatic careers, Torel guided other talented singers to paths on which he felt they would excel. The young Robert Goulet a member of that early Opera School cohort, steered by Torel towards musical theatre. In 1959. Goulet enjoyed a celebrated Toronto homecoming when he appeared with his colleagues, Julie Andrews and Richard Burton, in the world premiere of Camelot, which opened the new O’Keefe Centre (now branded as Meridian Hall).

In 1950, with the creation of the Opera Festival Association of Toronto, opera in Toronto would begin to branch into two distinct tributaries. The Opera School would remain an educational program dedicated to training, while the Opera Festival Association would in 1961 become the Canadian Opera Association and ultimately, in 1977, the Canadian Opera Company.

In 1963, the Opera School, now UofT Opera, moved to its new home in the Edward Johnson building, whose crown jewel is the MacMillan Theatre, named for Sir Earnest MacMillan, a former Dean of the Faculty of Music and founder of that short-lived opera company in the late 1920s. The theatre is a fully equipped opera house, boasting a stage width of 134 feet, line-sets capable of flying 38 different pieces of scenery and an orchestra pit powered by hydraulics to adjust to any level required.

One of the great advantages of the MacMillan was the opportunity it afforded for more sophisticated physical productions, including Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, Verdi’s Falstaff and Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Toronto audiences also heard many works for the first time there, such as Cavalli’s L’Ormindo, Ward’s The Crucible, Janáček’s Katya Kabanova, Respighi’s Maria Egiziaca, Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta, Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias, Vaughan Williams’s Sir John in Love and Handel’s Imeneo. Canadian premieres have included Paisiello’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, Debussy’s L’enfant prodigue, Rea’s The Prisoners Play, Searle’s Hamlet, Britten’s Paul Bunyan and Richard Rodney Bennett’s The Mines of Sulphur.

Following the success of The Last Duel, a new opera composed for UofT Opera by Gary Kulesha and commissioned by Music Canada 2000, the school inaugurated a workshop to give student composers experience writing opera, following a process of composition, dramaturgy, orchestration and staged public performance. The concept proved so successful that the workshop was ultimately introduced as a formal course in composition at the Master of Music level. For more than 20 years, the student composer collective of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music has become synonymous with creativity and innovation. Initial works such as Antigone and The Essential Hamlet drew upon established storylines, but gradually more sophisticated narratives were explored: the The Machine Stops effectively dramatized the E.M. Forster dystopian short story and Maid & Master, The Massey Murder, presented a compelling piece of Toronto history set in 1915, when Carrie Davies, an 18-year-old British maid shot Charles Bert Massey to defend herself against his sexual advances. Fearlessly tackling the challenge of operatic comedy, student composers produced the political satire, Rob Ford, the Opera, while the murder mystery parody Who killed Adriana? invited the public to fix the opera’s conclusion, necessitating the rehearsal of six different endings.

The present curriculum has been expanded beyond stage performance to include the implementation of a course for stage directors and répétiteurs. Masterclasses with established and developing artists provide a candid perspective on the realities of the profession while acting classes incorporate training for spoken text as well as the exploration of concepts expected of today’s performer. Sessions devoted to financial management and website design address the pragmatic aspect of building a career, while workshops in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion critically examine the role of the artist in today’s diverse society.

*this story originally appeared in our Spring 2022 print magazine

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.