“Something wicked this way comes,” announces one of the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, heralding the arrival of the mountingly murderous king of Scotland. In America’s capital this mid-November though, the words could, with a semantic twist, be aptly applied to Washington National Opera’s new production of Verdi’s version of the play. It was wickedly good.

Not all was perfect. “Abstraction heightens the psychological tension,” asserts a program note, but Erhard Rom’s sets – gauzy curtains for the witches’ scenes and a very plain “castle” of two tiers and a movable staircase – simply looked low-budget. The scene-setting drop curtain, with its flickering, shadowy images and quotes from “William Shakespeare,” pleasurably evoked the title cards of silent and early talking movies, promising a kind of picturesque old-fashionedness that Rom didn’t otherwise deliver. The handsome costumes, mid-ottocento in flavor, were puzzlingly attributed to no one designer; “a co-production of Lyric Opera of Chicago and Canadian Opera Company,” the program offers, tacitly suggesting that they’re Moritz Junge’s for David McVicar’s staging.

Brenna Corner’s direction started out on the wrong foot, with an overintellectualized vision of the tricky-to-stage chorus of witches as (again I credit the program notes), “souls of the dead lost in the wars,” some of them incongruously fond of flaunting their grands jetés. But Corner – the artistic director of Pacific Opera Victoria – quickly proved her mettle at moving her players meaningfully and creating (the witches apart) taut and telling stage pictures. For the opening of Act Four, she fashioned a particularly eloquent tableau, with its chorus of oppressed Scots mourning their fallen – and Rom at his best here, with a simple backdrop of the distant ruins of a fire-ravaged castle. And surely Corner merits at least partial credit for the cast giving so unstintingly of their individual and collective best.

Heading the strong vocal lineup was Montreal’s Étienne Dupuis, for whom the Washington Macbeth was the latest stop in a Verdi-dominated season that began in Vienna in September with a new Don Carlo, continues in Berlin in January with Rigoletto, and ends up in London in July with Il trovatore, with more Posas (Don Carlo) in Vienna and a pair of Verdi concerts in Southbank, Australia, sandwiched in between. That Don Carlo production, which I viewed via YouTube, is the single most egregious example of directorial overreach that I’ve seen in many a year, an infuriating travesty of Verdi’s great opera (Kirill Serebrennikov was the culpable regisseur), and I can well imagine Dupuis’s relief that the Macbeth Corner was asking him to play was recognizably Shakespeare’s and Verdi’s.

Photo Credit: Scott Suchman

Étienne Dupuis with Ewa Płonka as the murderous Macbeths

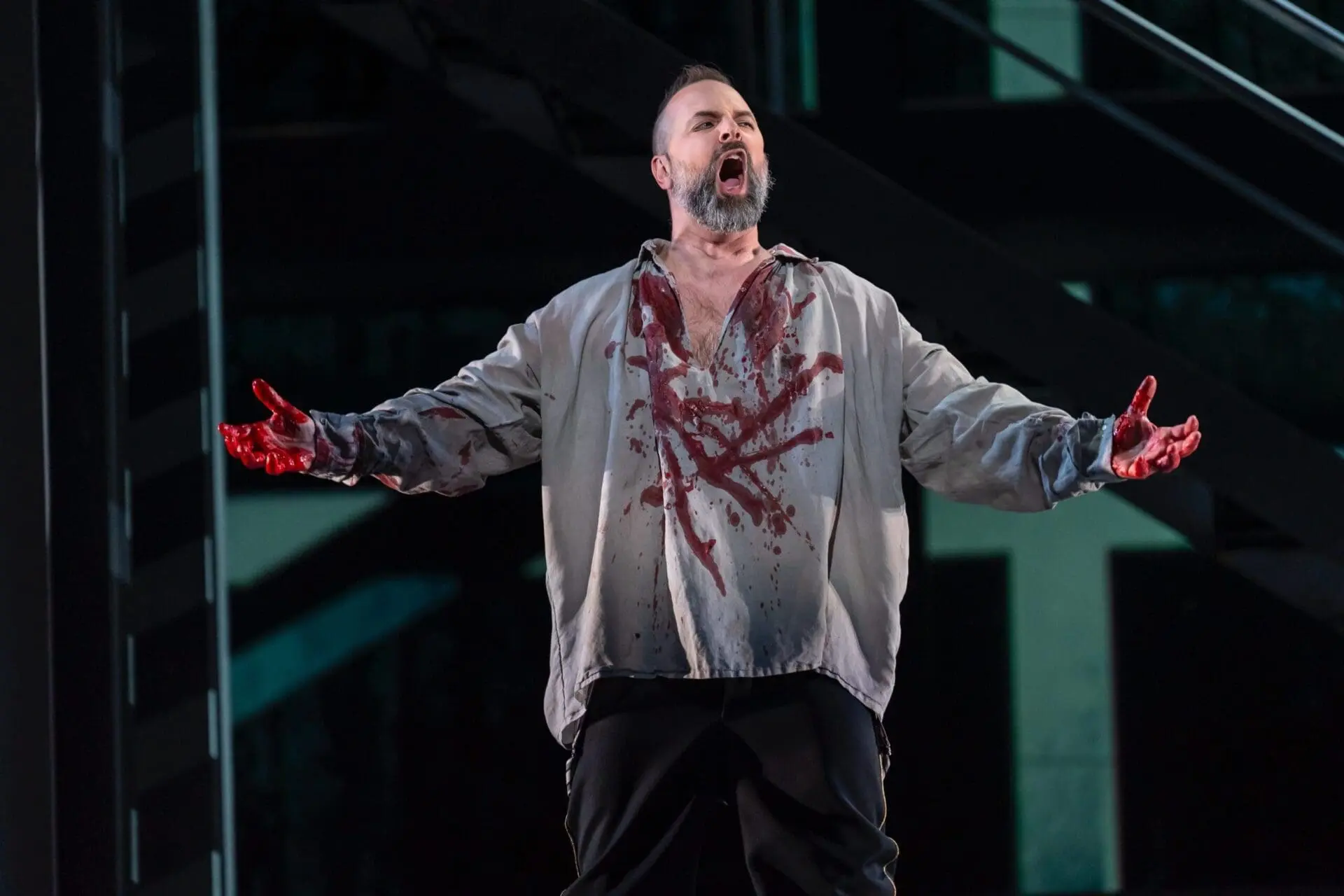

He did masterful justice to both its creators, his warm, supple baritone alertly responsive to every nuance of music and text. He and his director offered a particularly cogent death scene: felled by the not-of-woman-born Macduff, Dupuis’s Macbeth slithered downstage on his belly to sing his final, bitter “Mal per me che m’affidai” before Macduff’s coolly delivered coup de grâce, here a throat slice.

As the power behind the Scottish throne, Polish soprano Ewa Płonka was a striking departure from the hard-edged norm – a Lady Macbeth girlishly giddy at the bloodbath she’s unleashed. Announced pre-performance as “under the weather,” she began rockily, with an oddly botched reading of the letter (a technological mishap?) and a stodgy account of her big scena’s runs and roulades. The top notes, however, were vividly in place. Nor did “La luce langue” make an ideal vocal effect. But she handled the banquet scene’s Brindisi with a light and nimble command of its twists and turns, and the shifting moods of the sleepwalking scene were traced with a haunted delicacy, including a glancing stab at the infamous high D-flat. It’s a tough role, and Płonka impressed.

So did her less prominent colleagues. Soloman Howard was an imposing Banquo both vocally and physically – his ghostly appearances at the banquet were deftly handled. And the evening’s biggest internal ovation went to tenor Kang Wang for his unaggressively clarion delivery of Macduff’s “Ah, la paterna mano.” My, how that voice has grown since 2016, when I first heard him at Juilliard as Bellini’s Elvino! Fellow tenor Nicholas Huff sounded and looked just fine in Malcolm’s lesser duties, and soprano Anneliese Klenetsky, as the Lady-in-Waiting, was equally well up to her high-lying lines in the two big ensembles and to her fearful commentary on her mistress’s somnambulism.

The chorus, whether as witches, courtiers or oppressed Scots, sang rousingly. And WNO’s music director, Evan Rogister, kept a steady hand over everything, though I kept wishing for a bit more rhythmic flexibility, some rubato, some schwung. But I shouldn’t nitpick. It took a total of nine hours of travel to get to Washington and back, but this Macbeth easily justified the trip in only three.

Photo Credit: Scott Suchman

A blood-covered Étienne Dupuis in Washington

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.