The Opera Canada Awards—‘The Rubies’ makes a return to ‘live’ on November 15, 2021. Click here for more details to secure your ticket to this wonderful celebration of Canadian opera talent.

Long before anyone talked about finding a work/life balance, Canadian baritone Allan Monk was mastering the challenge. Over Monk’s more than thirty-year career on the opera stages of North America and Europe, performing roles both lofty and modest, he knew where his home was.

“My family has always been the centre of my life,” said the 2021 Opera Canada Awards, ‘Rubies’ honouree in an interview from his home in Calgary. “I turned down a lot of work because I would not ever be away for more than a month. I had other opportunities to go to Europe, and I turned them down because that was a long way from my family.”

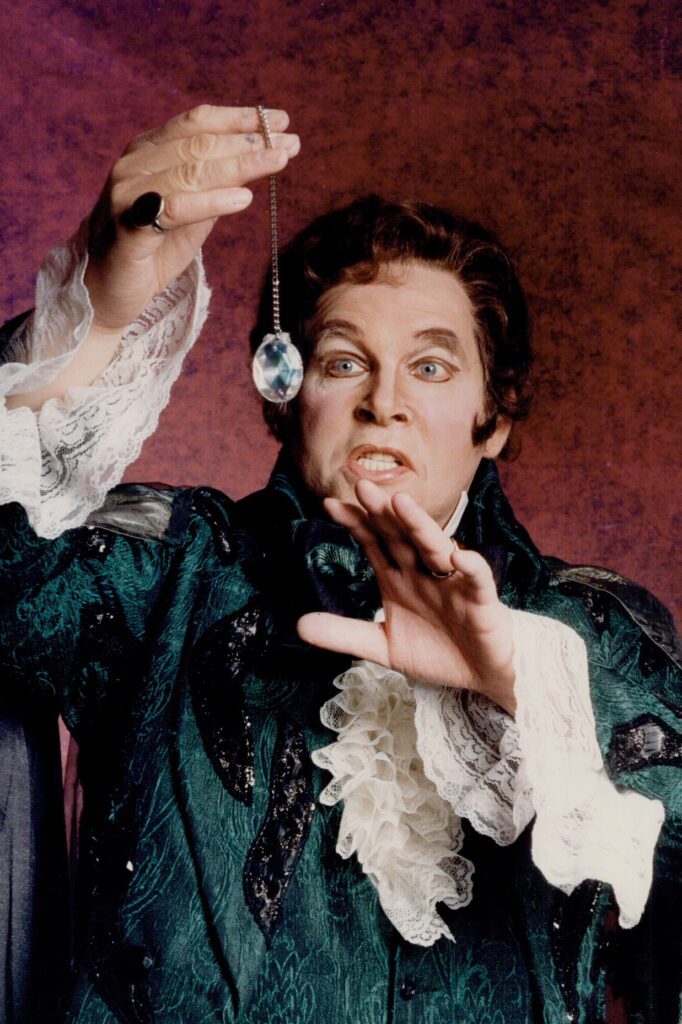

Monk sang lead roles with opera companies across Canada and beyond. Between 1976 and 1985, he was ensconced as a regular at the Met, and lived with his family in nearby New Jersey. He sang with the pantheon of his generation — Pavarotti, Vickers, Quilico, Carreras, but playing Schaunard to their Rodolfos suited him just fine.

“At the Met, I was happy to do the smaller roles such as Schaunard,” which he’d learned as an emerging artist in San Francisco. He was offered Marcello once, he said, and he turned it down. “I really enjoyed the success that I made out of that [Schaunard] part. Eventually I did Wolfram, Rodrigo, Ford and Sharpless [at the Met]. I was happy, especially in those first years, to be out of the spotlight, but in the excitement.”

He never had an agent, which meant he wasn’t at anyone’s beck and call.

“I was very happy controlling my life. A lot of time, an agent will book you into something and say you have to do it. This is important for your career. I know people who over a six-month period would be home nine days. And then you’d find out, oh, that marriage broke up.”

When his original family moved to Calgary from B.C. when he was a teenager, they all participated in community musical theatre productions. But his one and only private teacher, Elgar Higgin, was an opera singer who led him toward that style of vocal art. Monk was already familiar with opera since the whole family would listen to Saturday Met broadcasts when he was younger, and he loved the sound of the human voice. Higgin had sent another student to audition in San Francisco in 1965. The next year, “Elgar put a form in front of me, and said fill this out. I think you should go and audition for these people.”

Monk didn’t get anything out of the audition immediately, but a few months later, he found himself singing Figaro in San Francisco Opera’s Merola training program when another participant dropped out.

“That’s what got me into opera. It was right place, right time when they needed a Figaro in the summer, and it was right place, right time in November when they were starting a new touring program.”

When he went to San Francisco, his fellow emerging artists all had university degrees. “I was the only one without a degree. I didn’t even finish high school,” he said. His route to a career was unconventional, even at that time. “I auditioned, went to San Francisco, and [have been] working ever since.”

He spent 1969 to 1974 singing principal parts on American tours and small roles with San Francisco’s main company, before moving to New Jersey, where he sang with the Met greats, taking on dozens of secondary roles. He’s often asked if working with bigger stars ever intimidated him. It never did, he said.

In 1972, he had a small role in a San Francisco production of Manon that featured Beverly Sills and Nicolai Gedda. As a kid, he’d worn out a Gedda recording, he loved the Swedish tenor’s sound so much. And there he was singing with the master. Monk’s response was the same as it continued to be throughout his career. He learned his craft on the job, and Gedda was just one early opportunity to absorb the best ways to practice his art.

“I’m standing on stage, and I’m watching Nicolai Gedda, and I’m watching him sing, and you would think he was just telling you what the temperature was outside or what he had for breakfast. He was not exerting. He had wonderful craft. He could sing with ease.”

Monk also shared the stage with Plàcido Domingo early on. “I was in Domingo’s first Bohème in his San Francisco debut. To me, he was [just] Rodolfo. I didn’t know he was famous. The same with Pavarotti. I was treated as part of the team, and we were all just colleagues. I didn’t know enough to know that they were famous.”

Monk got his own share of raves over his career. The reviewer for an Edmonton paper covering a La traviata production gave him a unique compliment.

“Just as it is worth going to a boring Oilers tie just to watch the magic of Wayne Gretzky, so too is it worth heading to the Jubilee just to watch Monk weave his magic,” the writer gushed.

“I might be the only opera singer to be compared to Wayne Gretzky,” Monk said.

And in a New York production of Lohengrin, where Monk sang the Herald on short notice, the reviewer pulled out all the stops. “As the Herald, Allan Monk was perfection,” he wrote.

Monk has been out of the opera scene for many years. His life in Calgary has new sources of satisfaction. He helps care for his wife, and chairs a charity that supports the invention of devices for the disabled. He also volunteers with the local Alzheimer’s Society. When he speaks of his life now, he still views its centre as a group of families, the people that centred his life at the beginning, and the many extended communities that give him true purpose.

“I’m just so fortunate to have this chapter of my life as rich as it is.”

Don’t miss your chance to join in celebrating Allan Monk and all of our honourees at this year’s live Rubies event on Nov. 15th. Click here for complete event information.

Opera Canada depends on the generous contributions of its supporters to bring readers outstanding, in-depth coverage of opera in Canada and beyond. Please consider subscribing or donating today.