In fact—make that a three-in-one, points out Opera Atelier resident set designer Gerard Gauci.

Sandwiched between the two 17th and 18th-century French baroque pieces is a new, contemporary Canadian work by composer and violinist Edwin Huizinga and choreographer Tyler Gledhill. Titled Inception, it will open the second half of the program with a bare stage, allowing the audience to watch as the new set is gradually pieced together before their eyes while the music plays.

“It’s an unusual production for us because it’s essentially a triple bill. So design-wise, it’s a unique opportunity to give the audience three completely different visions on the stage,” explains Gauci.

“So the eyes will get a lot,” he chuckles.

Visuals have always been an integral part of Opera Atelier’s unique aesthetic. The company is among the few that specialize in Baroque ballet/opera repertoire, with intricate, historically accurate costumes and painstakingly hand-painted backdrops—and the 2018 season is no exception.

With a nod to the historic and political atmosphere of the time, the somber, moralizing tale of Actéon will be set in a dark, enclosed forest setting—and framed in tapestries. Gauci explains that the opera, written in the 17th century, would likely have been performed in an indoor reception area of a stately home, which typically had tapestry hangings decorating the walls.

“So it’s a reference to the kind of environment in which the first production would’ve taken place,” he explains. Gauci also chose a more earthy colour palette for Actéon’s costumes, which feature dark greys and maroons to match the themes of the opera.

“It has a darkness and heaviness to it that refers both to the 17th century and to the kind of story we’re telling,” he explains.

“This is a dark story, a story of punishment.”

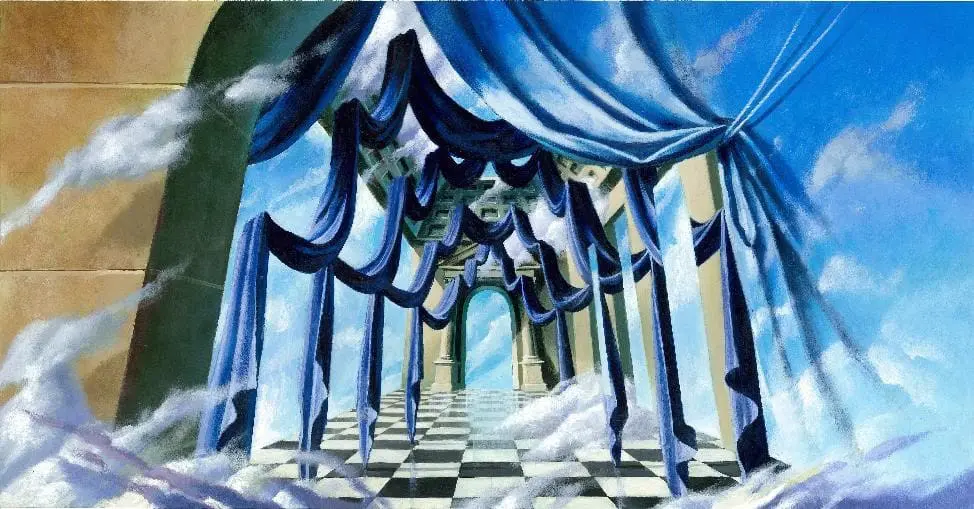

In contrast, Pygmalion is a more lighthearted piece, all about “entertainment and pleasure,” that Gauci has chosen to set “in the clouds.” Inspired by exuberantly decorative 18th-century Rococo design, Gauci draws inspiration from paintings of the period that depicted mythological gods set against the backdrop of light, blue skies.

“Because [the opera] is a surreal story, I wanted to meld the Rococo with the Surrealist movement, which was all about these dream landscapes,” he explains. “So scenically, this is an opera that happens in the clouds. All of the framing devices for the scenes are all blue sky and clouds, the sculptor’s studio is not a real studio, it’s more like fragments of architecture hanging in the clouds… that come together to create a mythological space.”

“Everything’s blue and white, very airy—the costumes are layered chiffon, so they move beautifully in the air when the dancers are moving,” he describes.

Part of the charm of an Opera Atelier production lies in such little details—the hyper-realistic backdrops, for example, are painted entirely by hand. They can take a team of specially trained artists up to a month to complete, with the group reproducing Gauci’s designs on vast swathes of soft canvas, working in unused industrial space in Toronto’s suburbs.

Opera Atelier’s season-opening double bill of miniature operas, both adapted from a Latin narrative poem by the Roman poet Ovid, are married by the evening’s theme of metamorphosis. Actéon, a miniature tragédie en musique, tells the tale of a young hunter who inadvertently chances upon the goddess Diana bathing with her nymphs. He is soon discovered, turned into a stag by the angry goddess and devoured by his own hounds. Pygmalion, on the other hand, narrates the story of a sculptor whose dearest wish is granted when a beautiful figurine of his own creation is brought to life by the goddess Venus.

Opera Atelier veteran and tenor Colin Ainsworth returns to star in the title role in both Actéon and Pygmalion. Ainsworth was also named the company’s first ever Artist in Residence, and will be sharing his expertise with up-and-coming Canadian singers in masterclasses as well as participating in Opera Atelier’s Making of an Opera workshop for high school students across the Greater Toronto Area.

Colin Ainsworth (Renaud) and Peggy Kriha Dye in the title role of Opera Atelier’s 2012 Armide. Photo: Bruce Zinger

The entire production is also set to travel to the US and Europe, in a tour that includes the Harris Theater in Chicago and the Royal Opera House at the Palace of Versailles, France—a feat which brings its own set of challenges, notes Gauci.

“I thought this show would be easy because there’s two short operas and another piece that basically has no scenery. But in fact, it’s been the most difficult show I’ve ever had to adapt to the other stages,” he admits. Each venue has its own set of idiosyncrasies and peculiarities—with Gauci having to recreate the set and position singers on differently raked stages than that of Opera Atelier’s home at Toronto’s Elgin Theatre.

Nevertheless, Gauci is excited for audiences across all three countries to enjoy “three completely different sets in one, with three completely different spirits behind them,” noting that such a phenomenon is a rarity in the opera world. “Normally, even with a single show, you’re moving from scene to scene but there’s a kind of aesthetic whole.”

With triple the sets, triple the stories and triple the visual richness, “I think it’ll be a very full, rewarding evening,” he says.