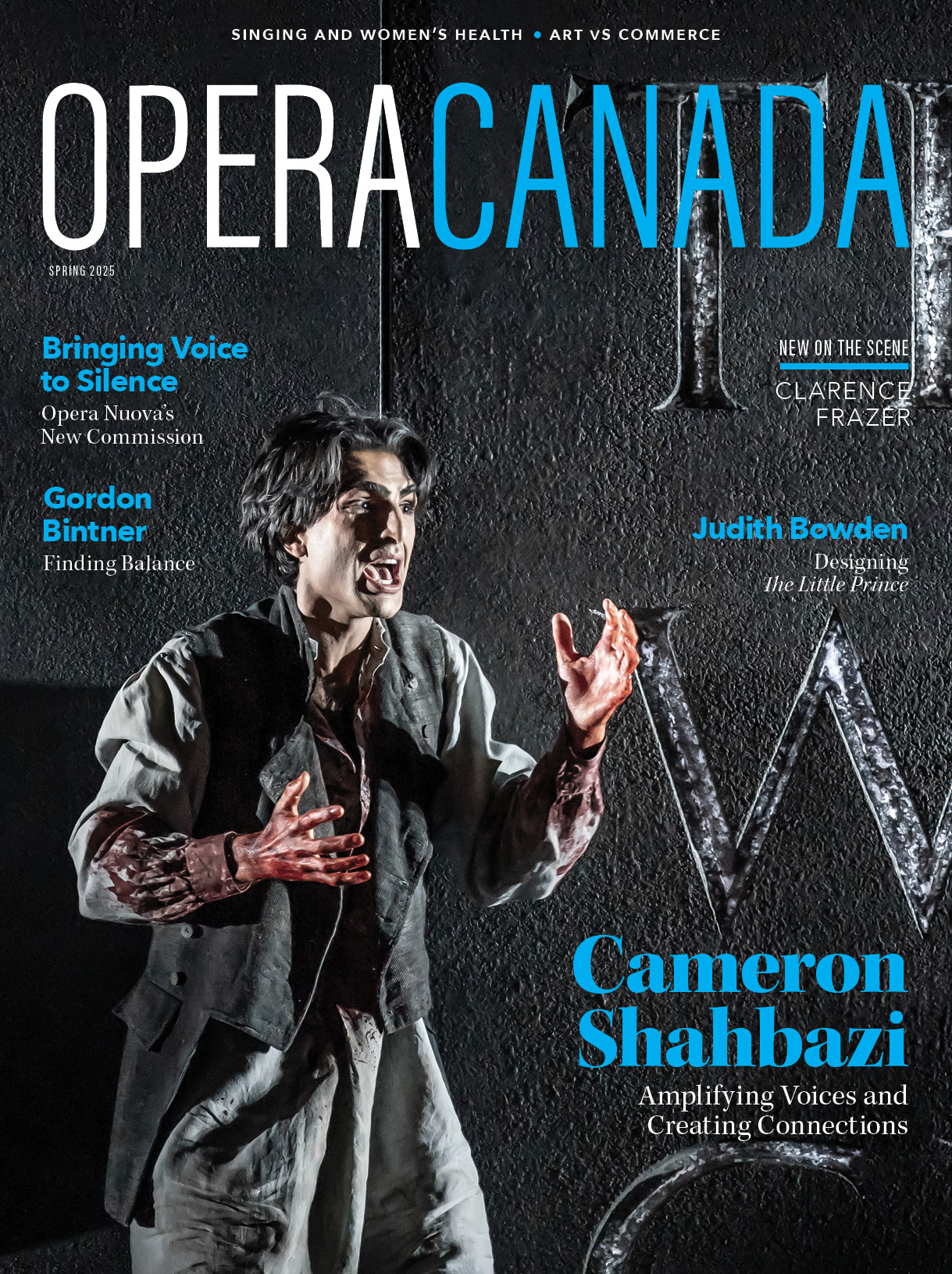

Canadian Opera Company’s season-opening, Eugene Onegin (seen Sept. 30th), was thrilling in its portrayal of gut-wrenching conflict and pathos as well as touching in its many sensitive and warm collaborations between orchestra and singers.

Tchaikovsky’s three-act opera, Eugene Onegin, was first performed in Moscow in 1879, and is based on Pushkin’s novel in verse of the same title. Robert Carsen’s production, originally developed for Metropolitan Opera in 1997, is as dynamic as it is sparse. Michael Levine’s set design keeps the focus on the characters with blank backdrops of solid colour and very few pieces of furniture on stage. While understanding Carsen’s intentions, the scenography felt too minimal at times, as in the final Act’s ballroom scene where the set was comprised of chairs alone, hardly creating the opulence or grandeur that signifies Tatyana’s transformation from country girl to countess.

Varduhi Abrahamyan (Olga) and Joyce El-Khoury (Tatyana) in the Canadian Opera Company’s Eugene Onegin. Photo: Michael Cooper

Act I opens with a view of an arresting orange sky and a blanket of fallen autumn leaves scattered across the stage. A beautiful ensemble for Madame Larina (Helene Schneiderman), Olga (Varduhi Abrahamyan), Tatyana (Joyce El-Khoury) and harp, sets an appropriately elegiac tone as they reminisce about past loves. Serge Bennathan’s choreography for Olga was a bit lackluster given how simply she walked around the stage while singing of being “playful and free.” Later in the scene, this was remedied soon enough by the heart-warming conclusion to Lensky’s (Joseph Kaiser) aria in which he and Olga share a tender embrace. The scene’s subsequent orchestral postlude was problematic as the flutes and horns could not quite agree on intonation.

The next scene opened with some lush string playing. Visually, we moved from warm, autumnal tones to an eye-catching blue sky, some rustic bedroom furniture, and a white gown for Tatyana that highlighted her innocence and naivety. An intimate scene between Tatyana and her nanny saw the young woman pouring out her heart in a letter expressing her love for Onegin. El-Khoury exhibited supreme control over quiet dynamics in this scene, offering a sweet sound while maintaining depths of emotion. This aria was a definite highlight of the production—it was transformative and magical.

Oleg Tsibulko (Prince Gremin) and Gordon Bintner (Eugene Onegin) in the Canadian Opera Company’s Eugene Onegin. Photo: Michael Cooper

In Tatyana’s subsequent meeting with Onegin (Gordon Bintner), after the delivery of her letter, he was portrayed coldly with his prim and proper attire and an upright, closed stance. The grey indifference conveyed by Onegin’s costume could have been more clearly opposed with a warmer coloured dress for Tatyana instead of the grey she wore—this would have outwardly demonstrated the difference in their emotional states.

Act II’s sparkling ballroom scene was a feast for the eyes with buoyant dresses swishing, pastel colours, ribbons, and joyous dancing. This visual excitement was accentuated by the orchestra’s string glissandi that added to the gay atmosphere. The lighthearted mood quickly turned to rage as an argument between Lensky and Onegin escalates into a duel. Kaiser demonstrated his masterful ability to command the audience’s attention here, and pull on our heartstrings, conveying pathos with his vocalism. The ensuing duel scene was eerie with its ominous timpani heartbeats accompanying a haunting duet between Lensky and Onegin. The giant sun rising after Lensky’s death, intensified the menacing atmosphere.

The final duet between Tatyana and Onegin was filled with sorrow and heartache. It was in this scene that Bintner came into his own—up until this point, his performance had seemed rather “safe” but with his ultimate aria, he was finally able to fully express Onegin’s anguish and grief.

The COC Orchestra, conducted by Johannes Debus, offered the perfect complement for the singers. The strings created a rich sound—many times the violins would opt for the G string in high positions, technically very difficult, but producing a powerful tone. In the winds and brass, the bassoon, clarinet, and horn solos particularly stood out as exceptionally sensitive. Tempi overall felt well chosen. The only misstep in this direction was in the too-fast tempo taken for the dancing in Act III, Scene i.

The COC’s Eugene Onegin was immensely entertaining and heart-stirring. All in all, an evening full of intimacy and tenderness, captivating acting, as well as beautiful and passionate singing.