Jane Archibald (Armida) with The English Concert’s Music Director and Conductor, Harry Bicket in Rinaldo at Carnegie Hall. Photo: Chris Lee

So, too, did the estimable Iestyn Davies, in the heroic title role: his soft-grained timbre better suited to Handel’s oratorios than to the wide-ranging bravura of his Italian operas. He wasn’t helped, either, by being the shortest man onstage; his height—an asset of his boyish David in Barrie Kosky’s Glyndebourne Saul—worked against him here. Sasha Cooke, as Goffredo, the Christian commander (the performance followed the gender distribution of the 1711 London premiere), projected more heroic dash despite her incongruous bare-shouldered getup and another lovely voice perhaps in need of further metal.

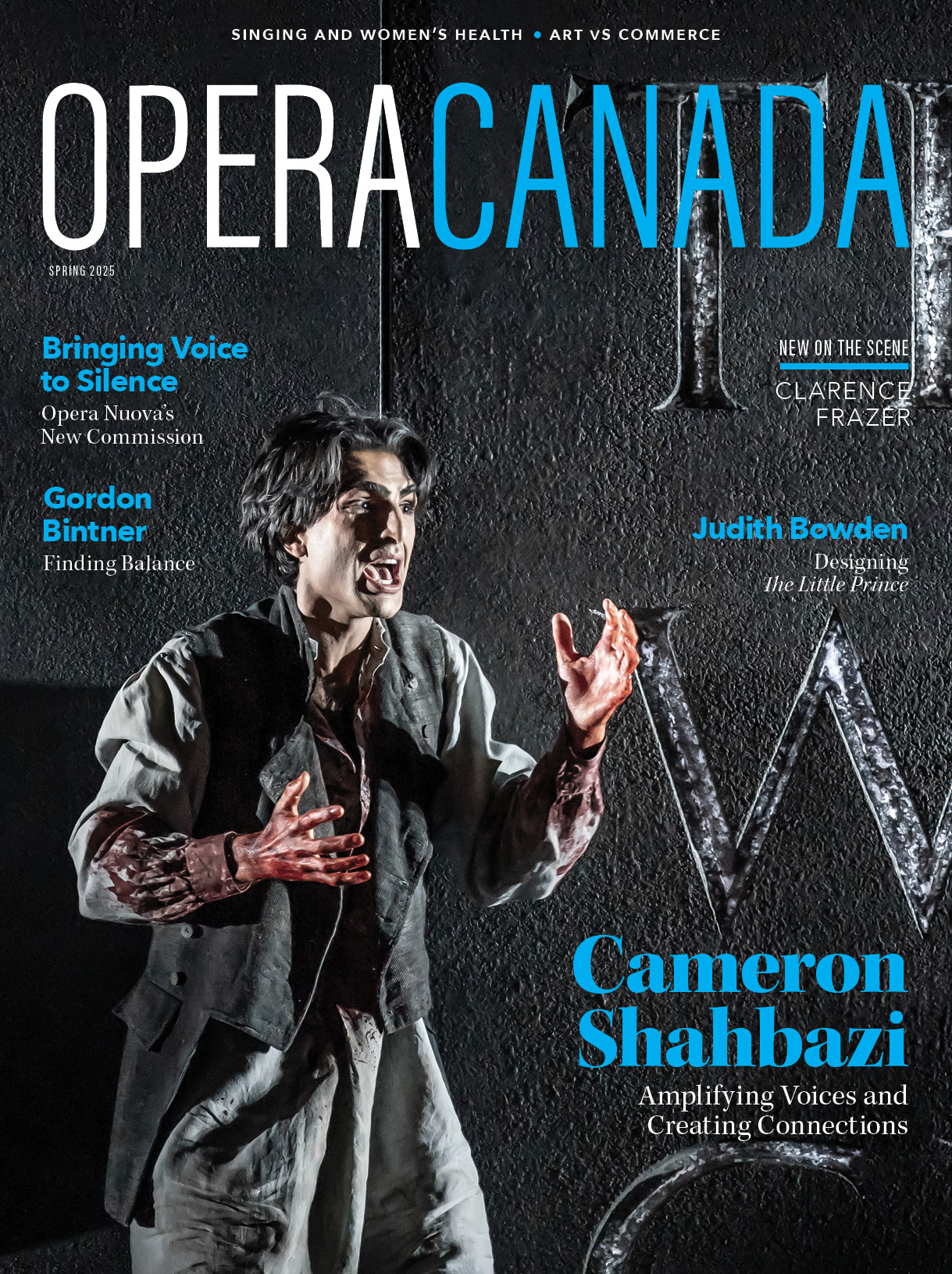

Countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński in Carnegie Hall Rinaldo

Fully worthy of Eustazio’s often-cut arias (he got three) and of the audience’s fervent acclamation, Jakub Józef Orliński showed a more even balance of satin and steel; the magnetic Juilliard-trained countertenor, newly signed to an Erato contract, sang Rinaldo in Frankfurt last fall, and I wished he’d sung it here, too. A third countertenor, James Hall, made a fine impression in a trio of gender-diverse roles. As Almirena, Joélle Harvey gave the best performance I’ve yet heard from her, responding tenderly to the simple, plaintive lines of the opera’s big hit, “Lascia ch’io pianga,” and to the ornithological seductions of “Augelletti, che cantate.”

Luca Pisaroni (Argante) and Jane Archibald (Armida) in Handel’s Rinaldo at Carnegie Hall. Photo: Chris Lee

Jane Archibald and Luca Pisaroni an ideal villainous pair in Carnegie Hall Rinaldo

But it was the opera’s two conniving baddies who dominated the show. Luca Pisaroni, maybe not quite so firm-toned or vocally limber as he was for Robert Carsen’s delicious Glyndebourne reimagining of 2011, still commands the stage with spot-on theatrical know-how. And Jane Archibald shone as the alluring, fickle-in-love, sorceress Armida, her diamantine coloratura ever a joy—nowhere more so than in her show-stopping “Vo’ far guerra,” perfectly paired with the comically indefatigable virtuosity of harpsichordist Tom Foster. But all of Harry Bicket’s crack period musicians shone under his stylish guidance, and everyone involved in this happy matinee deserved a laudatory palm.

Bayerische Staatsoper with Kirill Petrenko, Music Director and Conductor perform Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier at Carnegie Hall. Photo: Stefan Cohen

Lack of staging in no way hinders glorious Der Rosenkavalier at Carnegie Hall

Four days later, Archibald ceded the Carnegie stage to another stellar Canadian diva, Adrianne Pieczonka, when Munich’s Bavarian State Opera brought its long-celebrated Der Rosenkavalier, shorn of sets and costumes, across the Atlantic for an all-too-fleeting visit to New York. It seemed to me, in advance, an odd choice for concert presentation: I can think of few operas than demand as much precision-detailed stagecraft. But just as my ears adjusted to a decibel-deficient Handel, my eyes (and imagination) offered quick compensation to this scenery-deprived Strauss.

Adrianne Pieczonka goes straight to the Marschallin’s heart

In fact, I was relieved that I wasn’t being subjected to the errant ways of the last Rosenkavalier I’d seen—a rare misfire by Robert Carsen with his overthought staging at the Met—and happy that I was actually hearing a delectably audible Marschallin, Pieczonka, instead of the vocally parsimonious Renée Fleming. But Pieczonka (looking ravishing, by the way, in her Act I violet and Act III forest green) went far beyond mere audibility, with a lush loveliness that didn’t preclude light and shade but definitely banned all Flemingesque fussiness of style and manner: she went straight to the Marschallin’s heart.

Peter Rose (Baron Ochs) and Adrianne Pieczonka (Feldmarschallin) in Bayerische Staatsoper’s Der Rosenkavalier at Carnegie Hall. Photo: Stefan Cohen

Kirill Petrenko and Bavarian State Opera Orchestra are “breathtakingly lucid”

And that’s pretty much what I thought of the performance as a whole: fine, firm, and unfussy. Historically, among its maestri, there are two distinct Rosenkavalier traditions: the Viennese (in their personalized ways, the Kleibers, Karajan, Bernstein) and the German (Krauss, Keilberth, Böhm), with a good deal of cross-pollination between the two. The former aren’t afraid to embrace the sentiment, to hang on to it with the occasional well-placed swoon or sigh, then let go with another. Munich’s offering, under its brilliant departing music director, Kirill Petrenko (headed soon for Berlin and its Philharmonic), was clearly of the German bent: razor-clean, unindulgent, making all the requisite points with minimal ado and maximal impact. The opening of Act III—the busiest part of Hofmannsthal’s scenario—was breathtakingly lucid, and Petrenko built the opera’s glorious finale splendidly, with a particularly delectable orchestral bridge between the overtly emotional trio and the delicately simple duet.

A matchless ensemble

All of them scoreless, the cast delivered its well-practiced, full-bodied best: Angela Brower as a tall, droll mezzo Octavian with a zippy top; Hanna-Elisabeth Müller as a pellucidly sung, believably feisty Sophie; Markus Eiche as an unusually youthful-sounding Faninal; Lawrence Brownlee as a full-voiced Singer who scored by playing it straight. Peter Rose’s wasn’t the ideal voice for Ochs, but he knew every jot and tittle of the Ochs lexicon. Among the many others, Kevin Conners was the busiest man in Vienna as both the Marschallin’s and Faninal’s major domos and, moonlighting further, the Innkeeper in act 3; and Peter Lobert wielded a most impressive basso as the Police Commissioner once in the Feldmarschall’s (and maybe his wife’s, too) service. I guess I could pick a nit or two, but with a performance of such spark and stature, why even try?