SUBSCRIBE TO DIGITAL AND/OR PRINT MAGAZINE

*this text was originally published in the Spring 2023 print version of Opera Canada magazine

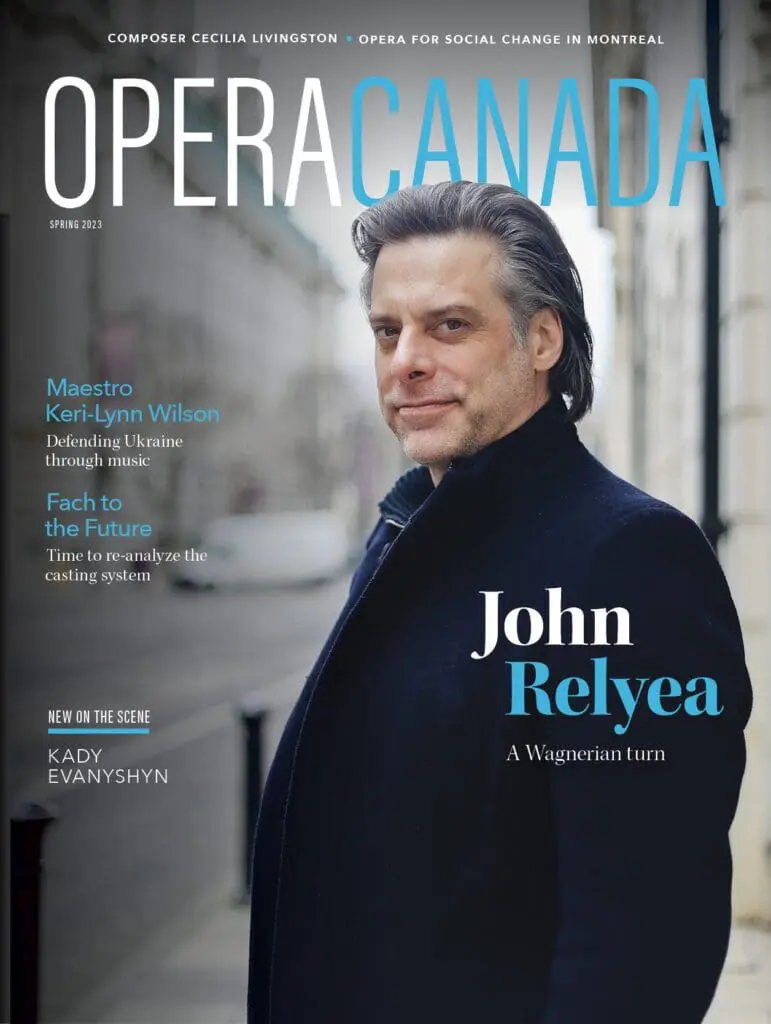

An international career now spanning 30 years, John Relyea is one of today’s finest bass-baritones.

John Relyea was anxiously preparing for his Metropolitan Opera debut as Alidoro in La Cenerentola when he happened to run into the legendary bass Sam Ramey. “Are you going to sing that impossible aria?” Ramey asked. Now, more than twenty years later, Relyea tells me from a London apartment, “That’s not what I wanted to hear!” After letting out a raucous and wonderfully resonant laugh, John collects himself enough to explain, “If Ramey’s telling me it’s ‘impossible,’ then I’m in big trouble!” Relyea, now at 50, is “focused on longevity.” In the realm of classical singing, the concept of longevity can be a loaded term. Perhaps he means vocal longevity, I thought. Many singers meticulously plan their vocal development as to not wade into roles that are “too heavy” too soon. But John isn’t worried about his voice. “I’m talking about my career.”

John’s now-thirty-year career has featured over two hundred and fifty performances at the Metropolitan Opera alone and regular appearances at virtually every major opera house in the world from Paris, to Chicago, to Vienna, to La Scala, and back again. The winner of the 2003 Richard Tucker Award, John boasts a repertoire that is equally varied going from Handel and Mozart all the way through Wagner and Stravinsky. The list of conductors under whom Relyea has sung is equally impressive: Pierre Boulez, Sir Neville Marriner, Zubin Mehta, Kent Nagano, Antonio Pappano are just a few of the long list of names. The towering Toronto native now sports longer hair and a short beard — a big leap from his clean-shaven and short-haired days starting out. When I remark on the change, he gives a wry smile and says, “It’s great. They don’t have to grey me now or anything. I’m just me.”

Over the last two seasons Relyea has completed a run singing his first Sparafucile in Bartlett Sher’s new production of Rigoletto at The Metropolitan Opera, as well as his first Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlo, and the ghost of King Hamlet in Brett Dean’s Hamlet, all in the same house. “When I was in my twenties I could absorb scores real fast. But I’ve noticed in the last year I could learn things really fast again.” Never content to rest on his laurels, John makes a point to say that he insists on challenging himself. “I took risks early on because I was restless. I wanted new experiences. I was drawn to a lot of different types of music. I didn’t want to be someone who did the same four or five roles. And I’ve done a lot of devils!” he laughs. I ask John if he ever regretted taking one of those risks. “Maybe Pagano in [Verdi’s] I Lombardi. That early Verdi is so tricky. Later [Verdi] is a totally different animal. They’re really schizophrenic roles. He hadn’t quite figured out what voice he’s writing for! One minute you’re a deep bass and the next you’re a high baritone. There’s a lot of negotiating and renegotiating the voice and the register. And that’s probably why I’ve taken to this Wagner stuff.”

The “Wagner stuff” in John’s case is a continuation of role debuts this season as he is currently in rehearsals for one of his biggest career moves yet: his first Wotan in Das Rheingold with English National Opera. Of Wagner’s one-eyed god, Relyea shared his own challenges in singing the role.

“I think the challenge is keeping Wotan as three-dimensional as you can. Of course, they’re ‘gods,’ but they’re so flawed. And it kind of lays in two arenas. Of course you want something big and heroic and strong. But you have to find soft, sympathetic qualities in the voice and the character. I wouldn’t say it’s a technique issue. I’m at the point now where I have the facility to do the technical things that would require me to bring out all those colours and experiment with mixing them.”

Growing up in the Toronto area, John was always musically inclined. The son of accomplished Canadian bass-baritone, Gary Relyea and noted professional singer Anna Tamm-Relyea, John grew up around classical voice — even learned to play the piano at the age of 4 — but “was rather indifferent to it because it was there all day long.” Of his father, Gary, John notes, “He structured his career really as a concert artist. He did oratorio 90% of the time. He still sings a little bit! And he was always a teacher.” John’s first musical passion arose as a teenager: his guitar. He understood immediately that because of his lower vocal range he would not be likely to sing lead vocals in a rock band. He began taking voice lessons with his father to help facilitate his secondary goal of— at the very least —being a backup singer.

“I remember one rehearsal where I was singing [backup vocals] and someone says, ‘You sound like Roy Orbison!’ and I said, ‘Shut up, man!’ And it’s a great voice! I should have taken it as a compliment, but we weren’t doing anything close to his type of music.” Shortly thereafter, things began to progress very quickly for the young Relyea. He auditioned for choruses and other concert work, and as he explains it, “By the time I was twenty I was singing for major orchestras in Canada. But I knew I had to study formally. It was kind of a crazy whirlwind at the beginning.” The formal studying John Relyea received was in the form of an undergraduate degree from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. “I was in the same class as [tenor] Juan Diego Florez and [bass-baritone] Eric Owens (now the head of Curtis’ voice department).” John then went on to be an Adler fellow with the San Francisco Opera leading up to his Metropolitan Opera debut in 2000.”

Although John is now a proud Rhode Islander, the Toronto native has great affection for Canada’s contributions to opera. “There’s really some great [voice] teaching going on in Canada,” he says emphatically. “Per capita, Canada has a very strong number of international quality singers. The strength is really in the university teaching system. A lot of great teachers in many different places. The singers arrive very well-trained in terms of their technique and their language.”

As I try to pivot toward addressing the business as a whole, John politely interrupts to make a final point. “There is one other thing I should say. The Canadian singing community in general is very community minded. There’s a very good amount of support from colleagues. I understand completely—and this is more how I am—the American mindset which is more about the individual of ‘I’m going to do this for me, I’m going to fight my way through this for my career.’ But the Canadian music scene is much more ‘let’s do this for the community.’ I would say it’s a great thing to have that kind of support.”

John Relyea established himself as a major player well before the digital age of HD simulcasts and grainy YouTube clips. A common theme among singers discussing the state of opera is the inherent contradiction of trying to advertise an acoustic craft through a “digital paradigm,” as John calls it. Essentially, how can we advertise the appeal of a performance of wholly acoustic sounds through the self-contradictory speakers, screens, and headphones? “I don’t know if I’m old-fashioned in thinking that it felt so special [in the late 1990’s]. You went in there and got a ticket and you’d tell all these people you saw it and the only way they were going to be able to feel that for themselves was for them to also go and get a ticket. It was this special place. It’s not to say it’s not special now. It’s just… different.”

In a recent New York Times piece, Metropolitan Opera General Manager Peter Gelb revealed that capacity has dropped from the pre-pandemic average of 73% to a startling 61%. “I saw that the new pieces did well and the traditional pieces didn’t do as well which was surprising to me,” John remarks. But he is optimistic about opera’s growing pains through modernity. He believes the “elitist paradigm” has frightened off some potential opera-goers and in a quick brainstorm suggests one small change: dress code. “It’s like when you put on a tux and tails. Yeah, sure, it looks cool but it’s constricting and pushes people away. I like when I can do a concert in a black suit. It’s one of those things tied up with the etiquette of ‘should we throw it away or not.’ Nobody’s going to throw a fit if you go to a concert and everyone is wearing a black suit. So what?”

Not unlike a Wagnerian leitmotif, John reiterates his focus on longevity. “I need to find the stuff that I’m going to be singing until…the end, you know? That stuff is out there.” If not Wotan, I ask, which role holds the crown as the pinnacle of his fach. “Boris [Godunov],” he says with no hesitation. “Absolutely. Boris. And I can’t wait.” As the subject comes back to the music, John’s enthusiasm for his Wagnerian turn cannot be contained. He speaks about it in an almost kabbalistic way. It is both a mountain to be climbed and a code to be unlocked. “At first when I was thinking of which Wotan to start with I thought I would start with Rheingold. Even up to a few months ago I thought ‘I don’t know about Walküre…’ Now, I’m thinking I probably could go there. It’s definitely higher and much bigger with more sustained singing. But something has really opened up [vocally] in the last couple years. We’ll see where it goes because there may be a Walküre in the future.”

But it is during the discussion of Wotan that we touch on the biggest role of John’s life: being a father of two. “Fatherhood gives a totally different sense of responsibility and a certain kind of unconditional giving. I did want to find characters who were younger when I was younger. I couldn’t relate to an old king or something,” he tells me. “I’m really just more being myself now when I go into roles of authority. You take it with you. There’s a certain natural charisma that comes with having a family and it does emphasize that quality.” I ask him the toughest question: of the two Relyea men, John and his father Gary, who would his father say is the better singer? John laughs and looks to the side ponderously. He finally says reluctantly, “I think he would say me.” I ask John to answer the same question. He thinks on it and again looks to the side. “Man…he’s got a great voice,” he says in admiration.

John Relyea as the Gravedigger and Allan Clayton in the title role of Brett Dean‘s Hamlet at The Metropolitan Opera Ⓒ Karen Almonds / Met Opera

Related content ⬇

Artist of the Week: 15 Qs for John Relyea

September 22, 2022

Our Artist of the Week is acclaimed, award-winning Canadian bass-baritone John Relyea.