SUBSCRIBE TO DIGITAL AND/OR PRINT MAGAZINE

*this text originally appeared in our

2023 winter print issue

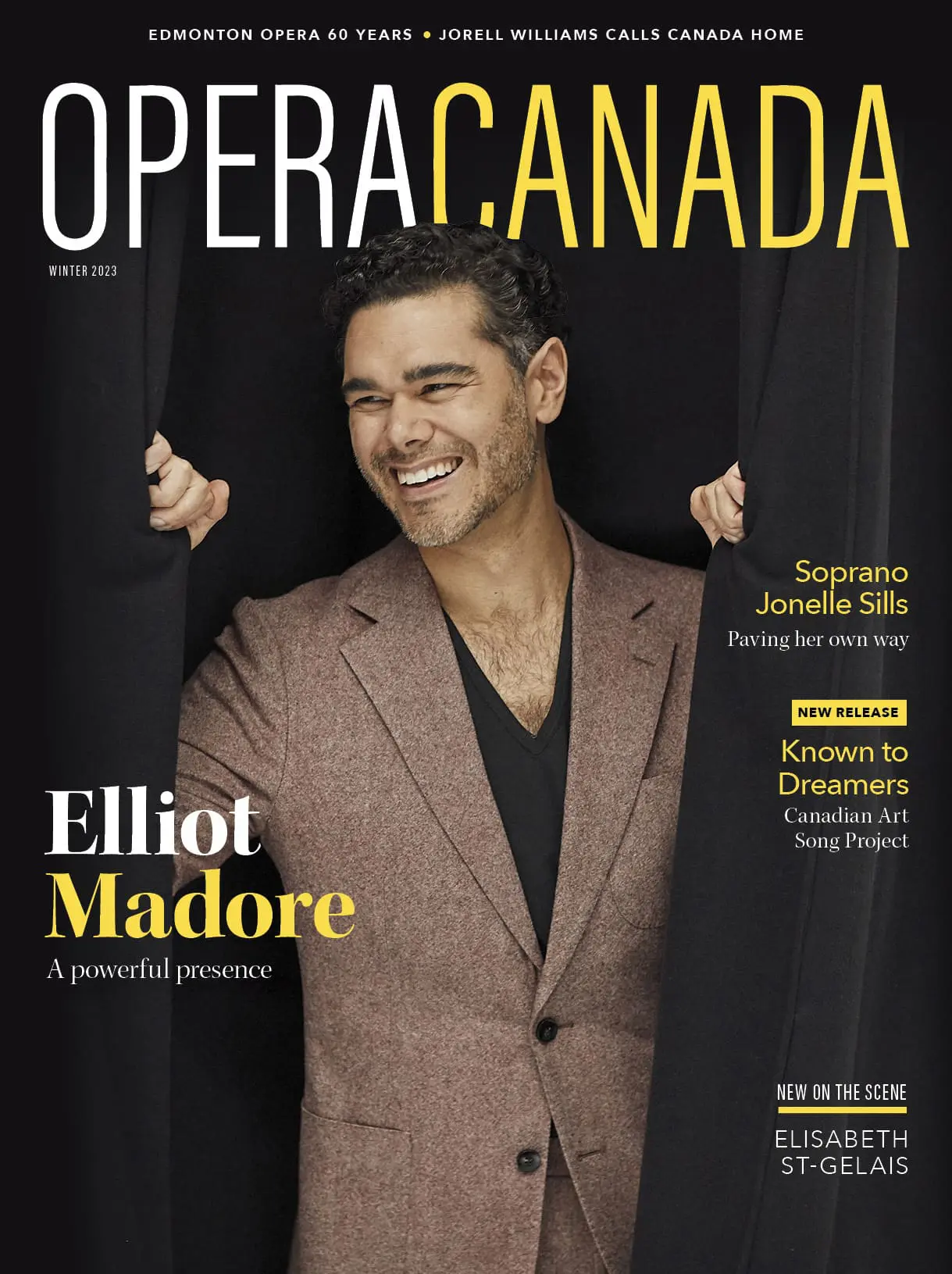

A Conversation with Elliot Madore

Lev Bratishenko talks to Madore, while the Canadian baritone is singing in Zurich, Switzerland – a city of great significance to him

LB: Hello Elliot in Zurich!

EM: It’s a really special place for me. My international career started when I was 24 and I was offered a position in the ensemble program in Zurich. And it’s where I met my wife, so I always love to come back. I’m currently here for Iphigénie en Tauride where I’m singing Orestes, which is a role debut; I’m having a lot of fun with this panicked, guilt-ridden, tormented character. And singing Gluck’s music is unique and surprising and very demanding for the baritone voice. I’ll be going back in December and singing Sweeney Todd. So, you can’t get more different roles, although both productions are by Andreas Homoki and that’s also so special. He has a clear idea of what he wants; he likes things to be active, very lively, which I really enjoy.

LB: So, would you say you’re anti park-and-bark?

EM: Very, very anti park-and-bark. I think that the closer we can get operatic singing and acting to being as human as possible, the more magical the performance becomes. We’re effectively doing superhuman things, singing over an orchestra into a four-thousand seat house, but then also acting like a human being. If you can find those one or two certain moments where you can still act human and sing operatically, it’s really beautiful. Not that I can do that all the time!

LB: I’m often surprised by how few people manage to act like humans even when they’re not singing, but I wanted to ask you about something else. Your career started so early, winning the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions at 22 years old and going to Zurich two years later, I’m curious about the transition afterwards. I think we don’t talk about it enough, which makes it seem like early success takes care of everything. What was that like for you?

EM: I had an uncommon trajectory. Typically you chip away at it and if you are able to attain a career then you’re usually in your thirties or even mid-thirties and you go from there. In my case, I went into the Met competition when I was 22, I started with my agent shortly after, I was in a young artist program immediately after that, and I left school early to pursue the career as much as I could. Being so young, there are still many things that you’re learning about yourself, both vocally and as an artist and as a human being. It was an incredibly lonely experience for me to move to another country at that age. I would say that I was just learning a lot about myself in the transition period. And it’s still surprising to me that I’ve been doing it now for 13 years. It’s wild. An opera singer buddy of mine and I always say to each other that just attaining the career is almost impossible; just supporting yourself financially is immensely difficult. Getting one or two seasons under your belt where you can say, we’re good to go for two years, but then you’ve got to sustain it. Because every time you go on stage, everyone has a certain expectation of you based on previous experiences and on who they think you should be as an artist. Actually, maybe this has something to do with how I was able to make the transition and sustain the career: I just view each and every day, and even each and every rehearsal as if it’s a performance. I think that focus and consistency have enabled me to ride the wave, as it were, to keep it going.

©Curtis Perry

Elliot Madore in the title role of Don Giovanni at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa; the production was a co-production with the Banff Centre

LB: Any advice for younger singers?

EM: Oh, man. I think every artist would say the same thing. You have periods of time where you feel like a god and you’re working beautifully and you get up on stage and the high notes are easy and it’s just no problem. And then you get into ruts. I mean, it’s the same thing with professional athletes; you have great years and years where it’s not so good. And I think the goal as a professional singer is to mitigate and make sure that it’s never a crash and burn scenario—that your worst is still pretty darn good. Something that doesn’t really get talked about enough for young singers transitioning into the professional world is that it has a lot to do with what kinds of professional experiences you’re having. For example, if you’re singing a role that maybe doesn’t fit your voice so well but your agent really wants you to do it; or if the set is acoustically unfriendly like you’re singing with a massive Verdi orchestra and there’s nothing behind you supporting the sound. That can be terrible. So sometimes it doesn’t actually have to do with how well you’re singing.

LB: You’re talking about artistry and control.

EM: So much stuff is out of our control. If you get a conductor who’s really sympathetic to the singer and advocates for a transparent sound and a little breathing room that can be a wonderful experience; but you can get a conductor who isn’t concerned about balance, for example, I mean that can be a nightmare scenario. So I think we have to control what we can and compartmentalize a lot of the rest. I understand the perspective of the opera house: they’re trying to plan and they want to get a good product out there. But the reality is that, as singers, we’re relying on vocal cords that are thinner than a piece of paper. It’s a risk-filled enterprise. So if you can market yourself as a consistent singer and a reliable singer that does go down incredibly well.

LB: How opera houses and audiences see singers brings up the topic of identity, which you’ve spoken about before. Are conversations about casting and race in opera going in the right direction?

EM: I’ve seen a lot of companies who have made important strides. Compared to, say, ten years ago there’s much more openness in terms of casting, like we are not relying on what someone looks like anymore but on what they sound like and what kind of character they’re bringing onstage. So, in that sense, it’s really encouraging. And I think new opera is going to be the driving force in the future; people want to hear it and more companies are realizing that. I can envision a world where in 20 years half of the productions at the Met are new works. With all these new works we’re doing away with the old typecasting world.

LB: I really hope you’re right. Has any new opera been particularly important to you?

EM: Even when I was in high school, I would listen obsessively to John Adams’s music so when I had the opportunity to premiere Girls of the Golden West in San Francisco that was a dream come true—and I got to work with Peter Sellars. I think John’s ability to tap into the modern consciousness is special. Even if he’s doing a historical work based on the gold rush in California and the atrocities that happened there, he’s able to connect it to so many of the things that we’re talking about and going through today. And I just love his music, the rhythmic intensity and melodic complexities that he brings. That’s his voice; he merges that with these stories that are so relevant today.

©Stefan Cohen

Madore as Romón and mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges as Josef Segovia in the world premiere of John Adams‘s Girls of the Golden West at San Francisco Opera, 2017

LB: So, what are you excited about next?

EM: Boston Lyric Opera is putting on Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice as a chamber opera at the Huntington Theatre, which is a beautiful and intimate venue. I’m incredibly excited to see what kind of sound world he will create in the space, and I think it’s so advantageous for Boston Lyric to do something unique like that. I’m also very excited to be a part of Buddha Passion; Tan Dun asked me to perform the role of the Buddha. He likes to call me his Canadian buddha. He’s very, very good. So far we’ve performed it in Seattle and at the Edinburgh festival. It’s a beautiful piece and I’m very happy to be part of it. It’s technically an oratorio, but Tan Dun likes to say that it’s an opera. It’s going to be staged soon but I can’t give any more away.

LB: You’ve been teaching at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music (CCM) for a few years now, how does this affect your performances?

EM: My interest in teaching is twofold: I enjoy doing it, to watch young singers grow and have these light bulb moments has a joy that can’t be found in performing. And also I’ve got two kids and obviously it’s incredibly difficult for an opera singer to have a family, to be in one place and not travelling all the time. And when I was interviewing for the job at CCM, they were adamant that I keep performing. And it’s obviously very, very busy and it’s not easy but I’m able to give much more to my students because I’m still active. I’m onstage and I can really relate to what they’re doing. And conversely when you’re teaching all the time and when you’re thinking about technique all the time, you’re singing gets much better. You’re always talking about it, you’re always thinking about it.

LB: You’re teaching yourself too.

EM: Really and truly. I’ve gotten much better as a singer and as a performer from teaching, and I think I’ve also improved as a teacher because of my continuing performances. I think it’s happening more and more. Maybe it has to do with the pandemic as well.

LB: The great diversification.

EM: A little bit of stability.