“Given in bits.”

Such were the words acclaimed composer Giacomo Puccini used to describe productions of Il trittico, his anthology opera.

“Brutally torn to pieces,” was his less diplomatic approximation.

Indeed, Il trittico, one of Puccini’s final compositions, has led a dismembered existence. Rather than presenting a single, cohesive narrative, Trittico is instead an anthology of three one-act operas, wildly spanning not just time and place but also tone. Starting with the gritty, dark, and violent verismo of Il tabarro, the triptych follows with Suor Angelica—a religiously seeped melodrama and Puccini’s personal favourite of the three—before concluding with the slapstick Gianni Schicchi, which evokes comedic tropes from the commedia dell’arte tradition . This tonal scatteredness, compounded by less-than-stellar reviews immediately following its 1918 premiere, compelled opera companies across the world to cherry-pick from the anthology, and turned the notion of presenting Trittico’s entirety into a novelty at best. And in the years since Trittico’s premiere, Gianni Schicchi, the only pure comedy Puccini ever penned, emerged as the favoured of the three, earning reverence as a masterpiece even as Tabarro and Suor were left to comparable obscurity.

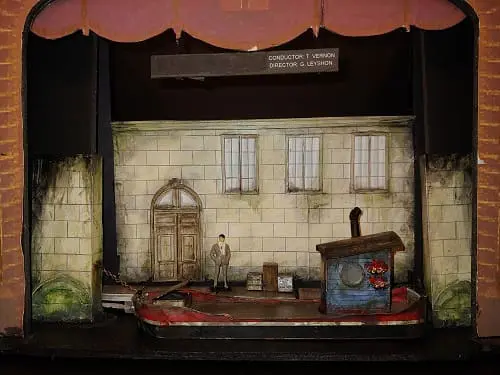

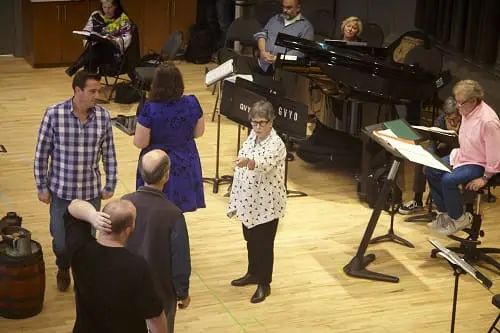

Yet after a century of critical sanctimony, reluctance towards Trittico as a complete piece is finally beginning to change. Riding on a tide started by recent productions, including showings at Metropolitan Opera in 2007 and Covent Garden in 2016, the trio is enjoying a thawing in attitudes, with more consideration taken to the oft maligned Tabarro and Suor as directors re-examine how the three pieces work as a whole. Now this quiet revival comes to Canada by way of Pacific Opera Victoria (POV), kicking off their 19/20 season with no shortage of ambition at the helm of acclaimed director Glynis Leyshon, whose previous dalliances with Puccini include La bohème and Madama Butterfly. I had the opportunity to discuss the upcoming production with her, and the challenges faced in putting on such a herculean show.

“These are being presented together as a complete evening… what are the themes between them?”

“That was staggering,” commented Leyshon on the differences between Il trittico and Puccini’s other works. “I had never really given a lot of thought… about the notion of an evening putting such wildly different stories together; and very different in terms of their musical tones.”

“As a director you’re thinking [about] yes, the truth and the core of what each of the pieces is about and means… but also that these are being presented together as a complete evening… what are the themes between them?” Leyshon emphasized that hers was not to present “three kind of cool stories” whose connections are merely “accidental,” but rather to “draw them into a mosaic, and give that mosaic a sense of cohesion.”

Not all would agree such cohesion exists. Critics often questioned whether Puccini even intended a thematic through line at all, or if he simply wanted to provide audiences with a varied operatic menu.

“I don’t disagree,” asserted Leyshon when presented with that interpretation. “We want to take a verismo, dark approach [in Tabarro]. We want to take a highly romanticized approach [in Suor]. Then we want to take a buffo comedy approach [in Schicchi] and kind of make a menu of that.”

And of course, the interminable search for theme can often backfire lest one is careful. “It’s not obvious. And I think you can force something unless you’re thoughtful in your approach.”

Thus the precarious balancing act: how much of a unifying theme do you try to coax from the trilogy while still maintaining the individual integrity of each individual piece? How much leeway are audiences willing to give, and will performers—who, it is worth noting, take on multiple roles across the three operas—manage the musical and emotional shifts in tone?

“Actors are excited by the notion of entering different tones and different worlds and different characters. But audiences…” Layton laughs. “‘Hey, I’m kind of on this serious road, why am I all of a sudden laughing at these things that are actually not funny. A man’s dying and being cheated,’ and so on and so forth.” She has a point, the whiplash can really rain on your parade (or parlando, as it were). So how to bridge this? The solution Leyshon offers is an ingenious one.

“I ultimately landed on the time that Puccini was writing. The idea of a setting just after World War One was very exciting and very telling.”

Leyshon is not the first to update Trittico’s setting in the name of cohesion. The Royal Opera House’s 2016 production did something similar, trading in Renaissance Florence for worn-down apartments in 1950s Italy in Schicchi, and a 17th-century convent for a Catholic hospital in Suor. What is innovative about Leyshon’s approach however is the choice to present the three operas in Paris at the same time, diegetically placing the characters and their events mere street corners from each other in a pastiche of Parisian life.

“I really wanted to be true to [Schicchi’s] commedia spirit”

“We see life on a pier on the Seine [in Tabarro where]… life passes by the façade of an imposing building that is a convent hospital.” During this piece the audience “only gets glimpses” of the hospital’s happenings while the story focuses on dock workers. “But in Suor Angelica we are taken inside [the hospital]. As with many spaces during World War One the soldiers returning are being treated in vast halls… in the convent.”

Yet the real challenge comes in incorporating Schicchi’s humour amid this spectre of war. “I really wanted to be true to [Schicchi’s] commedia spirit,” she explained. “So in our world, in this large hallway with the beds, the patients, and the soldiers, then become the audience for a troupe, a company doing the comedy of Schicchi. And in that [they] find the healing power of laughter.”

Leyshon takes special note of this latter theme. “I felt that [the commedia spirit] was important. I think it’s interesting that both Verdi in his Falstaff and this later-in-life piece that Puccini wrote turn to the idea of laughter as a healing thing… a deep and profound humanity is present in that.”

It certainly seems so given both Verdi and Puccini turned to comedy late in their careers and at the culmination of their artistic development. Evoking comedy as a balm to a bleak setting in the form of a “play within a play” is fiendishly clever, especially given Puccini’s own struggles chafing under the politics of World War One. During a time of increased Italian nationalism Puccini insisted on remaining politically neutral, earning criticism from both German and French contemporaries even before Italy formally joined the war 1915. Once his homeland threw its hat into the ring, Puccini’s problems, and his anxiety, only grew; he lost a friendship with the hyper-nationalist conductor Toscanini, struggled to premier La rondine after an exclusivity deal with Vienna went up in smoke, and was even threatened with arrest due to his frequent sojourns to Switzerland to visit a German mistress. In all the War was unkind to Puccini as it was to most everyone, and this gloom makes an ideal setting to not just tether all three operas spatially, but to thematically explore a turn to hope amid bleakness in both Puccini’s life and in the anthology of Il trittico itself.

“It’s not often you get this challenge,” notes Leyshon. “I think that’s one of the reasons we’re seeing Trittico emerge more now as an evening and not just one or two of them.”

“I’m hoping that in the aftermath that elements from all of the pieces will emerge… that’s my desire, obviously. There isn’t a weak link.”

And as for fears the audiences may be turned off as they were a century ago at Trittico’s premier?

“I think the wonderful thing from seeing what Pacific Opera [Victoria] has produced over the years is that they have created an appetite in their audience for works that aren’t the usual or the [most well-] known.”

In 1919, following its world premiere in New York, Il trittico enjoyed its Italian premiere in Rome. At the performance’s conclusion, Canadian tenor Edward Johnson, who’d played Rinuccio in Schicchi, dragged a bashful Puccini onto the stage to acknowledge the house’s applause. It is only fitting that, at the cusp of Il trittico’s return from the artistic wilderness, a Canadian company throws down the gauntlet. It is more fitting still that it does so in the hands of Leyshon, with the deeply considered, original presentation that the work has so long deserved.

Il trittico opens at Pacific Opera Victoria on Thursday, October 17th at 8:00PM.